Improving evidence uptake in education: The role of networks

We all know achieving evidence uptake in education is challenging. Despite the wealth of research available on what works to strengthen education systems, it often falls short of reaching the policymakers shaping decisions or the teachers implementing change at the school level. Networks that convene different education actors to share, co-create and collectively use evidence have emerged as one strategy to help address this persistent challenge; however, there is still limited knowledge on how education learning networks (ELNs) are, or could be, more effectively driving progress toward this goal.

The School Action Learning Exchange (SALEX), supported by the Jacobs Foundation, convenes ELNs and other education organizations to collaboratively generate and use evidence to drive better learning outcomes. In line with its mission, SALEX recently conducted a learning activity to better understand how ELNs can effectively support evidence use in education.

Key findings were published in a report and presented at the What Works Hub for Global Education’s Community of Practice Day in late September. They highlight how ELNs contribute to evidence generation, translation, and use, their role in fostering medium-term changes in practice and policy, and the factors that influence ELNs’ success in promoting evidence uptake within education systems.

Photo from the What Works Hub for Global Education COP Day: Strengthening evidence uptake and use by government panel.

Here are a few of the key takeaways and recommendations, which we hope can help inform the work of other learning network members, facilitators and funders both in and outside the education sector.

1. ELNs can support effective evidence use by engaging throughout the entire evidence lifecycle and by using a combination of complementary activities

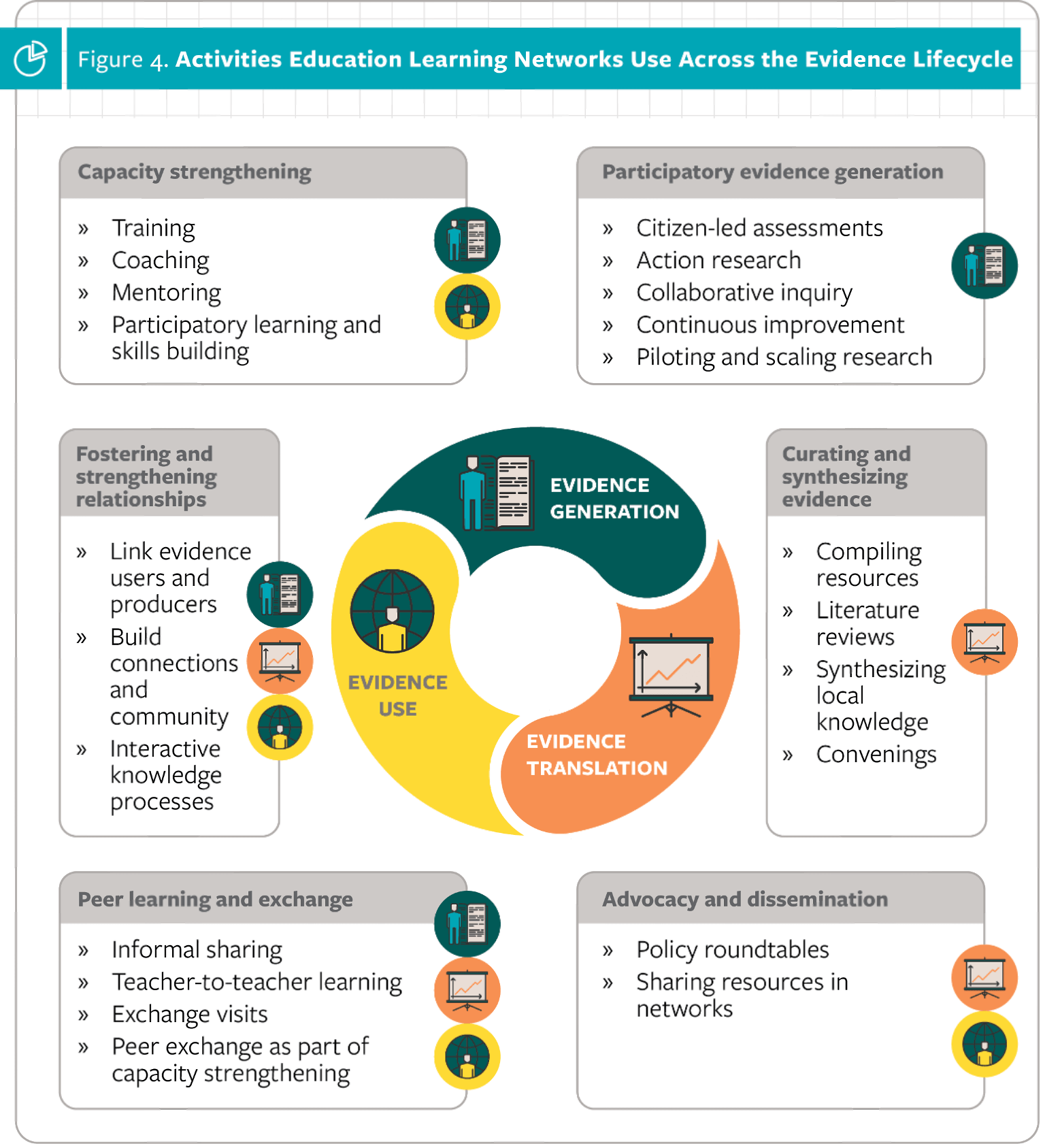

In the report, we divide the evidence lifecycle into three distinct, yet interconnected phases: generation, translation, and use. Across SALEX members, other key informants, and examples in the literature, we found that education learning networks can play a role in supporting evidence use throughout this entire lifecycle – and they deploy a diverse set of activities to do so (see figure below).

For example, ELNs made up of school-level representatives often use direct capacity strengthening approaches, including coaching and peer mentoring, to build leadership and strengthen school-level actors’ ability to adopt evidence-based teaching and learning practices (Mendizabal & Hearn, 2011). Other ELNs focused on participatory evidence production, like networked improvement communities, use continuous inquiry or improvement cycles to test, adapt, or scale promising practices or innovations that address common challenges (Feygin et al., 2020; Education.org, 2021; Didriksen et al., 2022; Proger et al., 2017).

Mapped along the evidence lifecycle, we grouped the main activities that ELNs used into six categories: capacity strengthening, participatory evidence generation, curating and synthesizing evidence, advocacy and dissemination, peer learning and exchange, and fostering and strengthening relationships.

Most SALEX members employ a variety of strategies to ensure effective evidence use. For example, the International Baccalaureate’s (IB) model emphasizes peer learning, capacity strengthening, and the curation and contextualization of evidence. They achieve this through virtual platforms like the IB Exchange, an interactive space for professional learning, and through in-person local associations, such as the IB Association of Japan, which hosts events for IB schools in the region.

Another SALEX member, UNICEF’s Data Must Speak Initiative, focuses on participatory evidence generation and capacity building by co-creating implementation research, conducting joint workshops, and producing tailored research outputs (e.g., reports, policy briefs) in partnership with governments to ensure ministries of education are engaged throughout the evidence lifecycle — and thus more likely to use the evidence that is produced.

While more research is needed to determine which activity is most effective and when, it is likely that a combination of approaches tailored to the context and goals of ELN members is best. The evidence lifecycle is less linear than it may sound — and by using a combination of approaches, ELNs can facilitate a more cyclical, relational approach to knowledge processes rather than an approach which supports evidence generation or dissemination activities in isolation (Révai, 2020).

For a full menu of activities that ELNs can use to facilitate effective evidence uptake, see Annex 1 of the SALEX report.

2. Limited time and resources, as well as power inequities and politics, can often constrain evidence use

ELNs in diverse contexts face similar challenges to promoting greater evidence use within education systems – some stem from factors within the network itself while others come from influencing factors in the broader education system.

For example, limited capacity among ELN members and other key stakeholders (such as governments) to apply evidence, as well as insufficient time and funding for an ELN to build trusting, collaborative relationships were cited as common constraints. Other external barriers, such as a lack of synthesized, context-specific evidence, government priority shifts, and the dominance of individual actors in decision-making processes can be particularly thorny challenges for ELNs to overcome.

However, ELN facilitators, members, and funders can design network activities that take these constraints into account, such as:

- Identifying policy windows early on to influence decision-making (e.g., new EdTech strategies or curriculum changes introduced by a ministry of education).

- Advocating for network funding over 5-6 years, allowing for ELN establishment and relationship-building in the first few years, with evidence work and scaling in the later years.

- Creating regular touchpoints for policymakers to engage directly with researchers and build relationships.

- Leveraging existing resources, like Results for Development’s collaborative learning toolkit and e-learning course, which offer practical strategies for building strong collaborative learning networks.

See Annex 2 of the SALEX report for a Drivers and Constraints Analysis Checklist where you can map out the barriers your ELN is facing, rank their importance, and brainstorm potential solutions.

3. ELNs across contexts should strive to be demand-driven, inclusive and collaborative as these are foundational ingredients for any effective collaborative learning network

SALEX members shared similar enabling factors for overall ELN functioning that aligned with those of other ELNs, including a demand-driven focus, strong relationships, a sense of community, and mutual trust. ELN facilitators and funders play a significant role in making this happen.

ELN facilitators should invest time and resources in developing trusting, strong relationships between members in the ELN’s early years to set a foundation for collaboration. Regular, in-person meetings and events, with ample time for informal networking, are particularly effective for relationship building. ELN funders should also prioritize sufficient funding opportunities for members to build trust and relationships (e.g., via in-person convenings such as the Schools2030 Global Forum) and to directly collaborate with each other (e.g., grants for joint projects such as SALEX catalytic funding provided by the Jacobs Foundation).

Finally, ELN funders and facilitators should allow for ELN work on evidence generation, translation, and use to be driven by the goals and shared interests of members. This requires flexibility and transparency on the part of funders during the ELN design and inception phase as well as throughout the life of the ELN at key milestones or decision points. Trust and strong, collaborative relationships are central to ELN functioning and thus a prerequisite to effectively supporting evidence use through a networked approach.

For a step-by-step guide on how to develop your own theory of change to support evidence uptake through your network, see Annex 3 of the SALEX report.

While there is still much to learn about the role of networks in supporting effective evidence generation, translation and use in education, we hope these takeaways provide guidance and food for thought for all those on this learning journey.

For more detailed findings and recommendations, check out the full report here and let us know what you think.

References

Didriksen, H., Solowski, K., Ash, J., & Kieninger, K. (2022). Using continuous improvement cycles to improve attendance: Lessons from New York and Ohio’s rural research networks. National Center for Rural Education Research Networks. https://ncrern.provingground.cepr.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/ncrern/files/ncrern_attendance_case_study_updated.pdf?m=1668523318

Education.org. (2021). Calling for an education knowledge bridge: A white paper to advance evidence use in education. Education.org. https://education.org/white-paper

Feygin, A., Nolan, L., Hickling, A., & Friedman, L. (2020). Evidence for networked improvement communities: A systematic review of the literature. American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/NIC-Systematic-Review-Report-123019-Jan-2020.pdf

Mendizabal, E., & Hearn, S. (2011). International Institute for Educational Planning Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies: A community of practice, a catalyst for change. IIEP research papers. Overseas Development Institute. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000212379

Proger, A. R., Bhatt, M. P., Cirks, V., & Gurke, D. (2017). Establishing and sustaining networked improvement communities: Lessons from Michigan and Minnesota (REL 2017–264). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Midwest. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573419.pdf

Results for Development & Collaborative Impact. (2024). Collaborative Learning Networks Measurement & Learning Framework. https://r4d.org/wp-content/uploads/CL-Framework-External-5.10.24-B.pdf

Révai, N. (2020). What difference do networks make to teachers’ knowledge? Literature review and case descriptions. OECD Education Working Papers No. 215. OECD. www.oecd.org/edu/workingpapers