5 things we’ve learned from a bottom-up approach to health system strengthening

Traditionally speaking, public health planning is often driven by central-level policies and resource allocation that trickle their way down the health system. If you only start at the top, however, you miss the bigger picture. Subnational health managers are on the frontlines of health care delivery. They supervise, coordinate and monitor health activities, engage community members and confront the real-life obstacles that prevent people from accessing health care. In short: They’re the implementing agents that make the health system function.

In low- and middle-income countries, however, public employees working at the subnational level rarely feel empowered to make decisions even around the day-to-day problems that they face; and there are a lot of challenges on the frontlines—even more so in contexts where resources are scarce, infrastructure is lacking and community members are dispersed.

As one of the implementing partners for USAID’s flagship Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP), Results for Development (R4D) is working with subnational health managers (and national level policymakers and managers) to overcome these challenges. Since 2015, R4D has led a bottom-up action planning and management process with regional and district-level health managers in Tanzania and Guinea, called the Comprehensive Approach to Health Systems Management.

And this is what we’ve learned:

1. One size (or approach) does not fit all.

The first step in the Comprehensive Approach process is to work with the health managers to identify the biggest challenges or bottlenecks they’re facing and to map the root causes of these challenges. A root cause analysis is an important component, because it helps managers take a step back from their assumptions about why something isn’t working and dig into the underlying issues. However, it’s a hard exercise to think through. To make sure it is a useful process for teams, the approach must be tailored to local contexts, and flexible enough to support evolving health systems.

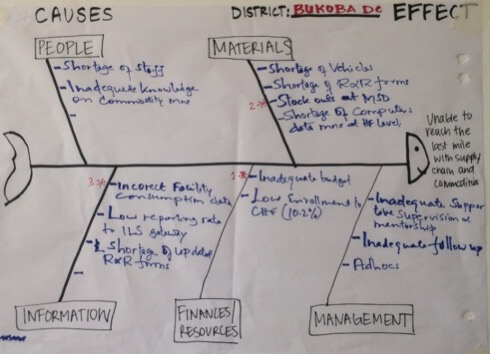

In Tanzania, fishbone diagrams were used to conduct root cause analysis during regional workshops with health management teams in Mara and Kagera regions. Fishbone diagrams are simple visual charts that allowed the teams to systematically review bottlenecks and gaps across people, materials, information, finances/resources, and management that might be impeding health system performance.

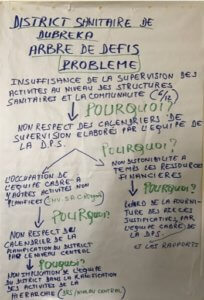

While the fishbone worked in Tanzania, it was clear from the beginning that it wasn’t the right fit in Guinea. As teams thought through why problems existed, their natural inclination was to think vertically and across the different categories of the fishbone. Flipping to a vertical problem tree and using the “five whys” to probe deeper into the root causes helped the teams work through the analysis in a way that felt more natural. The metaphor of a problem tree also helped to reinforce why finding root causes are important: if you only trim the branches of a tree, it’s still there, but if you eliminate the root, the problem is solved.

2. Sometimes different problems have common root causes.

These root cause exercises spanned numerous health systems challenges and bottlenecks but they often pointed to common, systemic issues. In one region in Guinea, four of the five district teams identified what, at first glance, are very different priority problems. These included insufficient supervision and lack of community awareness among others. Through the root cause analysis process, however, all four teams realized that their problems were traced back to a lack of coordination with local stakeholders. While the problems and stakeholders may have varied, the missing capacity was the same.

3. It’s important to be proactive and to use the resources you have.

During a workshop in Guinea, an enthusiastic participant described what the Comprehensive Approach meant to her using a local proverb: If a snake is about to bite, you should use the small stick you have rather than turning around and running for a bigger stick.

It is easy to wait on the arrival of a “big stick” solution to problems in the health system such as additional funding from national level leaders or a donation of materials and equipment from partners. But ultimately, the Comprehensive Approach is about the subnational managers being proactive and learning to more effectively use the resources that they have around them. This means taking ownership of problems and figuring out what can be done locally to address them. This is particularly important given that the effects of national-level change take time to be adopted as policies trickle down to affect the activities on the frontlines of the health system.

If you just sit around waiting, the snake could bite.

4. It takes a village.

Engaging the right stakeholders at the right stage of the planning and management process is essential to make sure that local needs are met, local resources are used and that the community feels involved.

For example, in Guinea, the team sought to bring together a variety of actors. This meant that, instead of bringing together participants only from the health sector (health facilities and health managers), the workshop included municipal representatives, community members, implementing partners and potential investors in the region.

And, as a result, a key first step was to make sure everyone understood the term “health system” in a broad sense and what each of them—even those not directly involved in health—could do to help improve health outcomes in their communities. Bringing all of these people together helped to kick-start better collaboration with a wide array of stakeholders and started to build relationships that the district teams can continue to use moving forward.

5. It works!

The Comprehensive Approach is working.

In Tanzania, eight of the 17 district councils that participated in the Comprehensive Approach workshop reported improved enrollment rates in district level health insurance, an indicator of growing local investment and trust in the health system, five reported reduced stock outs of essential commodities and three reported higher rates of facility deliveries. Collectively, results of this kind suggest improved health system performance.

While the process is ongoing in Guinea, there are already successes in the making. District health teams have integrated their priority problems into their annual work plans, and the Ministry of Health is looking to scale-up the Comprehensive Approach across the country for both planning and training programs. This local ownership and adoption of the process has the potential to impact the entire health system rather than just the few districts participating in the program. This means that the Comprehensive Approach can continue to help subnational managers generate local solutions to local priorities in the ever-evolving health sector.

Photos © Meera Suresh for R4D/MCSP