Does the World Need Another Toolkit? 4 ways to use transparency, accountability and health resources from the T4D Project

[Editor’s note: This is the third post in a series that is sharing insights from a Harvard Kennedy School and Results for Development joint program that is evaluating whether it’s possible to improve citizen voice and empowerment while improving maternal and newborn health at the same time. Read the first post and the second post.]

We told ourselves we would not build another toolkit. Really, we did.

Ever since the transparency and accountability field fell swiftly in love and fiercely out of love with toolkits, the idea of creating something that you could take out of the box—but that probably was too simple to actually work in 99 percent of situations—appealed to no one working on our project. And so we focused our energy on building something new.

We worked together to build something that was flexible to different problems in communities, rather than assuming every village had poor maternal health because the midwife did not show up to work (for example).

We worked together to build something that was flexible to different contexts, giving communities the power to, for example, work with village officials in a collaborative way to fix problems if the officials were more reform-minded than the service providers.

And we worked to build something that was compact, replicable and scalable, and that would not take years and millions of dollars to implement in a small number of places. The more funding and time that is required of CSO facilitators, the more difficult this would be to scale up if it works. And so we sought to design something that only required minimal resources and time.

You can read more about what the intervention ended up looking like and the guidelines we used to co-design it on our website and in our upcoming intervention design report. But in short, what we ended up building was a process for sharing information about problems with health services and for helping communities build ways to address these problems. And we designed a set of resources—like scorecards and social actions stories – that could be used together or individually for information sharing and social action design in other communities, in other countries, and in other sectors.

A set of resources—in other words, a toolkit. So how can we best put this particular toolkit (and the tools therein) to use? Here are four ways that we recommend:

Wholesale adoption. Maybe the most straightforward way to use the intervention materials is to use them as a full kit. For practitioners who are interested in building citizen empowerment and participation to improve maternal and newborn health, we have the full set of materials that we co-designed for Tanzania and for Indonesia available. This includes a facilitator manual that outlines every part of the intervention, facility and beneficiary surveys that provide the data for the scorecards in each country, and the social action stories that provide ideas for different approaches that communities can take to improving maternal and newborn health.

This set of tools could provide a foundation for practitioners interested in applying an intervention of this type in their own country—with minimal adaptation. While we are still evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention itself in Tanzania and Indonesia, the early signs are promising. And so we wanted to make these tools available for any organization seeking to lead similar work in their own country.

Using the social action stories. While using all of the tools in the toolkit is one option, the individual resources by themselves could provide valuable input into the work of practitioners. We compiled the social action stories as a response to the often prescribed actions of transparency and accountability interventions. We wanted to find ways to encourage community members to make their own decisions about what actions to take to overcome health problems; at the same time, we recognized that it would be helpful for communities to have some initial ideas and examples off which to build.

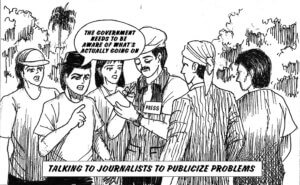

Our answer: the social action stories. These stories provide real examples of communities in Tanzania, Indonesia, and in other countries that were able to work together to push for change – in collaborative and confrontational ways, working with everyone from government officials to media to fellow community members, and using a range of different approaches. Practitioners working anywhere—and on any issue—could use these to provide real cases and ideas to communities that they are trying to encourage to undertake their own local actions.

A cartoon used to illustrate a social action story in Indonesia. © Transparency for Development/Sylvia Kartowidjojo

Using the surveys for maternal and newborn health work. An important part of any transparency and accountability intervention is the information that is shared to encourage action and accountability. For the T4D intervention, we wanted to build a scorecard that would share real local information on all of the possible contributing factors to poor health in mothers and babies. That meant digging beyond purely facility problems and looking at issues having to do with knowledge, culture, and access.

The results of this design are our scorecard surveys for each country. First, each country had a more traditional facility survey, focusing on problems with medicines and equipment, workers, and other aspects of health facilities. Our CSO partners also implemented a beneficiary survey in each country, asking women who had recently given birth questions about their maternal health care decisions and their reasons for these decisions. This second survey allowed us to understand some of the cultural and knowledge-based obstacles to proper maternal and newborn healthcare.

We do not know if there surveys are the best way to collect information, and they are more complicated than some information tools in transparency and accountability interventions. But they do allow users to collect information on the range of potential problems that underlie poor maternal and newborn health. With relatively small adaptations, these tools could be used both by transparency and accountability practitioners and by health practitioners in other countries.

Using tools to inform problem-driven design. And what about practitioners who are NOT focused on maternal and newborn health? The surveys actually provide some lessons for other sectors as well. In designing these tools, we wanted to move away from the traditional approach of focusing on a specific type of problem—like absenteeism or corruption.

And so we designed surveys that collected information on different buckets of obstacles that could stand in the way of better health outcomes. This includes problems with service quality (information we collected from both facilities and women) as well as problems with access to care and knowledge/culture. Investigating the full scope of problems that could contribute to maternal and newborn health is how we arrived at our survey designs. These problems—about service quality, access, knowledge, and culture—are also problems that apply to other areas of health, and education, and other sectors. And so the surveys can be used as a guide for developing different surveys—in different sectors—to take a problem-driven approach to development breakdowns.