3 key insights on moving from modeled evidence to policy decision-making

Modeled evidence can be a valuable tool to help decision-makers choose between complex trade-offs.

We define modeled evidence as evidence generated from mathematical models that simulate different potential health scenarios, including scenarios around disease transmission, and/or the impact of different policy interventions on health outcomes. 95% of surveyed modelers and decision-makers in one World Health Organization survey agreed that modeled evidence should be used to inform guidance for public health recommendations, particularly to determine the relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of various interventions (Norris et al., 2018).

However, decision-makers do not always use modeled evidence. Reasons including a lack of policy-relevant models, the perception that models are too complex to understand or based on too many assumptions, and a lack of trust between decision-makers and modelers often stemming from limited engagement or interaction (Knight, G. M., 2016; Campbell et al., 2009; Innvær et al., 2002; Oliver et al., 2014).

The inability to ensure that decisions are informed by the best available data can result in losses in efficiency, effectiveness, and impact, which affect the end users of health systems.

So, how can we improve policymakers’ access to and use of high-quality mathematical models for decision-making?

Results for Development (R4D), Access Health International; the Health Policy Research Group of the College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, Nouna Health Research Center of the National Institute of Public Health of the Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, and independent consultant Peter Muriuki collaborated to understand critical lessons for this knowledge translation work in Burkina Faso, India, Kenya and Nigeria.

Here are 3 of our key takeaways from this research as we worked to understand how to bridge the gap between the production of modeled evidence and its use in policy and program decision-making.

1. We need to take an ecosystem-level approach — investing in the development of models alone is not enough to influence health policy and practice

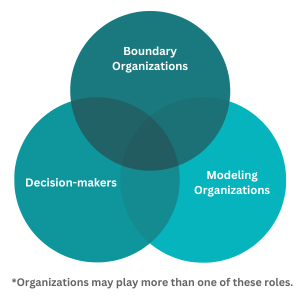

Modeling exists in an ecosystem of evidence generation and use, by which we mean the system of the various actors who are involved in producing, translating, and using evidence, and the ways in which they relate to each other.

Figure 1: Modeling to decision-making ecosystem actors, definitions used in this study

| Modeling Organizations | In-country or international organizations/researchers that produce modeled evidence |

| Boundary Organizations | Stand-alone organizations that help to distill findings and present them in easy-to-understand formats, foster dialogue and exchange, and engage decision-makers and modelers in debating the impact of evidence on policy or practice |

| Knowledge Brokers | Individuals or entities typically embedded within research/modeling organizations that help to distill findings and present them in easy-to-understand formats, foster dialogue and exchange, and engage decision-makers and modelers in debating the impact of evidence on policy or practice |

| Knowledge Translation or Translation

|

The process of putting evidence into a format that is easy for decision-makers to understand and use |

| Decision-makers | Users/potential users of modeled evidence and those who participate in making decisions for national and subnational health policies and strategies |

Modeling investments that result in policy- and decision-making impact take the needs of the full ecosystem — from the researcher to the decision-maker — into account. Investments in the production of modeled evidence without consideration for demand, timing and policy relevance are less likely to play a role in informing policy and program decisions. Because the evidence to decision-making ecosystem varies widely among countries, mapping this landscape and assessing the strengths and limitations of the relationships among the different actors is an important first step in strengthening systems to support the production and use of modeled evidence in decision-making.

Modeling investments that result in policy- and decision-making impact take the needs of the full ecosystem — from the researcher to the decision-maker — into account. Investments in the production of modeled evidence without consideration for demand, timing and policy relevance are less likely to play a role in informing policy and program decisions. Because the evidence to decision-making ecosystem varies widely among countries, mapping this landscape and assessing the strengths and limitations of the relationships among the different actors is an important first step in strengthening systems to support the production and use of modeled evidence in decision-making.

Figure 2: Main producers of models according to our key informants in Burkina Faso, Nigeria, India, and Kenya

| In Burkina Faso, government advisory groups, such as the COVID-19 thematic working group, provide a platform where modelers and decision-makers can come together to discuss modeled evidence around various diseases, most prominently COVID-19. |

| In Nigeria, disease specific and general health or data government advisory groups provide this platform, along with prominent and independent National Council on Health. |

| In India, independent consortia of researchers (such as the COVID-19 consortium), provide this platform, while government-led “working trainings” provide unique opportunities for modelers to come together to develop models needed by decision-makers while developing their own modeling capacities. |

| In Kenya, disease-specific government advisory groups and task forces (most prominently the COVID-19 Task Force) provide this platform, while formal partnerships between government and modeling agencies provide another avenue for communication. |

Among the ecosystems that we studied, we observed a focus on awareness building to introduce and spark interest in modeling concepts in less developed ecosystems such as the nascent modeling to decision-making ecosystem in Nigeria. Such ecosystems may need more technical support in organizing, interpreting, prioritizing, and communicating modeled evidence. Highlighting early modeling success in the pool of evidence used to engage decision-makers in policy dialogue can help spark demand for modeled evidence among decision-makers in countries where modeled evidence is still new. Governments in such ecosystems could benefit from committees established for outside modelers providing technical assistance to coordinate their support to governments and avoid providing conflicting or confusing messages.

For example, communications products on modeling in the lesser developed modeling to decision-making ecosystem in Nigeria are likely to be conducted by boundary organizations — or stand-alone organizations that help to translate evidence, distill findings, foster dialogue, and impact policy or practice — with limited communications capacity. In the more developed ecosystems that we observed, such as in India, modeling organizations tend to have developed their own communications capacity for knowledge exchange.

On the other hand, we found that India and Kenya, where demand for modeling is already present, needed support to:

- Build long-term, sustained modeling capacity;

- Build platforms for knowledge exchange between the many actors involved in modeling; and

- Develop local data systems for the development of contextually-relevant models.

One of our key informants in India highlighted the need to build capacity to produce, interpret, and communicate models in a specific subsector:

If you take health services, for example, there are very few people who can really look at the data analysis, and that kind of capacity building doesn’t happen…nowadays it’s an age of data we need more and more people can look at data and build models and draw conclusions and advise the policymakers. So, at several levels, we need capacity building both in generating data as well as in what I would call crunching data.”—Knowledge Broker, India

When funders design investments in modeling from an ecosystem perspective, they can recognize that a wide array of high-capacity actors must be engaged to effectively move a model from the design phase, through creation, and into eventual impact on policy. Beyond investing in modelers, funders and other actors must think about the production, mobilization, and use of evidence.

2. Knowledge translation mechanisms and approaches come in different shapes and sizes

Platforms that enable knowledge exchange and translation between researchers and decision-makers allow for more complex, relevant, and multi-disciplinary models. In addition to boundary organizations and knowledge brokers — or individuals that may sit within modeling or decision-making organizations and help to translate evidence, distill findings, foster dialogue, and impact policy or practice — such platforms include government-led advisory groups and task forces, independent researcher consortiums, model co-creation workshops that also train new modelers, and formal long-term government-research partnerships under memoranda of understanding. Of these, government advisory groups were the most common and engaged to some degree with modeled evidence in all the ecosystems that we observed.

Figure 4: Mechanisms for enabling the translation of modeled evidence for decision-making

| Government Advisory Group | Consortium | Working Trainings | Formal Government Research Partnerships | |

| Definition | Government-led advisory groups, task forces, or technical committees of experts & modelers that review available evidence & advise the government | Partnerships between NGOs, research/academic institutions & other stakeholders that regularly review & discuss evidence to provide guidance and advocacy to decision-makers | Training sessions, often organized by or with the government, that bring together researchers to develop modeling capacity through the collaborative development of a model | Formal ad hoc partnerships, including contractual arrangements & memoranda of understanding, established by the government with organizations that develop models to jointly explore key research questions |

| Examples | Nigeria’s National Council on Health | • India’s SARS-CoV-2 Genome Sequencing Consortium

• Nigeria’s COVID-19 Research Coalition |

• India’s Cochrane & Campbell Collaboration trainings

• India’s Center for Global Development International Decision Support Initiative |

Kenya MoH’s commission of a report on COVID modeling efforts |

| Strengths | • Allows for visibility of available evidence

• Provides space for discussion & debate • Improves transparency • Directly tied to decision-makers |

• Allows for wide visibility of available evidence

• Provides space for discussion & debate • Improves transparency |

• Develops capacity

• Encourages transparency and collaboration • Promotes government leadership in modeling |

• Intentional collaboration

• Clear expectations |

| Pitfalls | May have limited membership | May not have direct ties to government | Requires organizational & convening capacity, including funding for experts | Certain partners may have favored status, limiting the pool of modeling expertise & diverse perspectives |

It is important that knowledge translation mechanisms in an ecosystem are appropriately developed and tailored to the country’s context. Knowledge translation mechanisms are more successful when they are structured to ensure sustainable, open access to model results and notes on methodology, data sources, and assumptions. Grants should include time, budget, and plans for linking to relevant knowledge-sharing mechanisms in a particular country, such as task forces, advisory groups, and research collaboratives.

For example, in Kenya, the government often partners with research organizations to commission reports that answer specific policy questions, such as policies for managing COVID-19. These partnerships provide a platform that ensures the relevancy and timeliness of modeling efforts for decision-makers.

3. COVID-19 pandemic: a catalyst and magnifying glass for capacity development needs

In times of crisis, we often act quickly to exchange information, make decisions, and roll out government responses. And the COVID-19 pandemic was no different.

Many countries demonstrated that they could quickly set up different mechanisms to bring researchers together with policymakers in a context that necessitated epidemiologic modeling and the use of modeled evidence in the pandemic response. Burkina Faso’s COVID-19 Thematic Group, India’s National and State Taskforces for COVID-19, Kenya’s COVID-19 Taskforce and Nigeria’s COVID-19 Research Coalition are just a few examples of well-structured mechanisms that used modeling studies to inform prevention, control, and management of COVID-19 cases and guide the pandemic’s trajectory.

One of our key informants in Burkina Faso highlighted what made COVID-19 modeling so successful in the country:

The key success factors for COVID are the people who were involved, because they were fairly well-established national experts, which meant that people had confidence in the model and also because the modeling data was much closer to reality, because there was a first model, then the model was adjusted, so that even in terms of estimation, the data was much closer. So, it’s really the quality of the model that was a success factor as well as the skills of the group of experts.”—Decision-maker, Burkina Faso

The heightened use and strengthening of modeling during the pandemic helped to increase global awareness and acceptance of modeling as a key tool for decision-making. A culture of transparency and data sharing between modelers and users of modeled evidence has helped to facilitate partnerships and the exchange and translation of information.

The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a catalyst for spurring interest in modeling as a form of evidence. Countries have an opportunity to build on this momentum, including building on the mechanisms that were established quickly to bring modelers and decision-makers together in reviewing evidence and developing recommendations to keep citizens safe. Emerging lessons from the pandemic highlight considerations such as:

- A need for donors to coordinate with existing modeling efforts to avoid duplication;

- A need for sustained funding to build long-term modeling and knowledge translation capacity, and;

- Internal committees for external modelers providing technical assistance to decision-makers to coordinate their efforts.

One of our key informants in Nigeria highlighted the need for more streamlined global coordination on modeling production:

We are involved in a lot of international discussions around infection prevention and control in the Ministry of Health, every sector is screaming, ‘Data! Data! Data!’ Everyboday is emphasizing on the need for quality data. In WHO, NCDC, data is everybody’s watchword…the fact that the world is a global village; people want to know what is happening. Anything that is happening to one country is relevant to other parts of the world.”—Decision-maker, Nigeria

Long-term capacity development and investment needs to take place to ensure its place in the evidence landscape for the long-run and allow countries to be better prepared for the next crisis.

Read more

You can learn more about each of our country team’s research findings and recommendations for funders, decision-makers, modelers, and boundary organizations and knowledge brokers, here. And to support the practical use and application of these recommendations, check out the end of our global report for a working list of monitoring indicators to help funders and implementers assess the progress and success of investments in countries’ modeling ecosystems, here.