Reducing corruption risks in the extractives industry

Leveraging transparency to reduce corruption

Earlier this month, on Dec. 9, the United Nations observed International Anti-Corruption Day, a day recognized since the 2005 U.N. General Assembly “to raise awareness of corruption.” Given the timing, it seems fitting to share a bit about Results for Development’s (R4D) journey through the Leveraging Transparency to Reduce Corruption (LTRC) program — especially as we prepare to launch our first research projects in Nigeria and Peru in early 2020.

LTRC is an action-research joint initiative of the Governance Program at Brookings Institution, the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), and Results for Development’s Accountability and Citizen Engagement practice. The five-year program pilots and learns from evidence-informed strategies to reduce corruption risks and tackle different dimensions of corruption in the management of natural resources, with special emphasis in extractives (oil, gas and mining). These research projects are defined and co-designed with local stakeholders, so they respond to the specific concerns and priorities of organizations committed to the fight against corruption in their respective countries.

Recognizing the delicate and complicated nature of the corruption challenge in the extractives sector, LTRC also aims to develop country-focused research agendas that promote the debate of different approaches to overcome the contextual implementation gaps and institutional challenges each country faces in their own anti-corruption efforts, and which typically cannot be subject to experimentation and pilots.

The problem

Many resource-rich countries (RRCs) face extreme and intractable corruption challenges, as is well documented in the literature. In too many cases, resource wealth that could support growth and development instead fuels plunder, bribery, and continued poverty (Sala-i Martin and Subramanian 2013; Ross 2015). The paradox of resource wealth is that it appears to inhibit, rather than support, efforts to achieve sustainable economic growth and development, as evidenced by the increasing concentration of extreme poverty in RRCs relative to non-RRCs (Auty 1993).

A common explanation is that natural resource wealth creates more incentives and opportunities for corruption. Once corruption undermines citizens’ trust in government, citizens are then less likely to actively cooperate with — or even support — efforts to clean up the system (Morris and Klesner 2010). Similarly, if businesses perceive a corrupt system in which their competitors have stronger political connections, they are more likely to bypass courts, pursue extra-legal benefits, and pay bribes (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann 2003). Thus, corruption leads to a vicious cycle and deterioration in the institutional quality necessary to productively manage resource wealth (see, for example, Kolstad and Wiig 2011; Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian 2013). Longchamp and Perrot (2017) argue that if the wealth of all-natural resource dependent nations were used to pursue anti-poverty goals, by 2030 more than half a billion people would be lifted out of extreme poverty.

The TAP-Plus approach

LTRC began with a global evidence review to identify the most promising transparency, accountability, and participation interventions, policies or programs to be adapted and piloted in different geographies. Our annotated bibliography and evidence map published by Brookings Institution, as well as our upcoming foundational paper, are the result of this effort to understand what the evidence, and the gaps in evidence, are.

The mixed evidence on different transparency, accountability and participation (TAP) interventions revealed a common thread. It is the integration of these approaches, together with the careful consideration of what we call “plus factors,” that holds the most promise in tackling corruption. In fact, a review of TAP interventions, programs and policies shows that these plus factors, when considered at the design stage, improve performance.

While LTRC’s upcoming foundational paper will provide additional details, our framework classifies those plus factors as institutional reforms, implementation gap considerations, and context dimensions. Thus, said factors can be considered as part of the intervention design, or as key environmental conditions that either constrain effectiveness or open windows of opportunity for enhanced performance. In practice, what this means is that these factors can be used either as specific components of the strategy, or as key environmental factors that need to be tackled beyond a specific, localized pilot.

The conclusions from the review are consistent with recent calls for more integrated approaches and strategies that address corruption from both government (top-down) and citizen-led (bottom-up) sides (for example, see Dewachter et al, 2018 or Fox, 2015). However, the program’s approach is the first attempt to build a framework for strategies specifically aimed at fighting corruption in extractives.

LTRC in action

Using the TAP-Plus approach as a lens to understand the existing landscape for anti-corruption efforts, LTRC has engaged in significant consultations with local stakeholders representing civil society groups, governments, and industries in Nigeria and Peru, with plans for additional scoping in Mongolia, Colombia and other countries in 2020.

For instance, our efforts to build a research agenda in Nigeria starts with two key research projects. The first research study assesses mechanisms to bolster citizen engagement in budget tracking processes at the subnational level, acknowledging and dealing with an environment of low confidence in anti-corruption efforts. Secondly, we will conduct formative research around citizen perceptions and concerns on fuel subsidy reform in Nigeria.

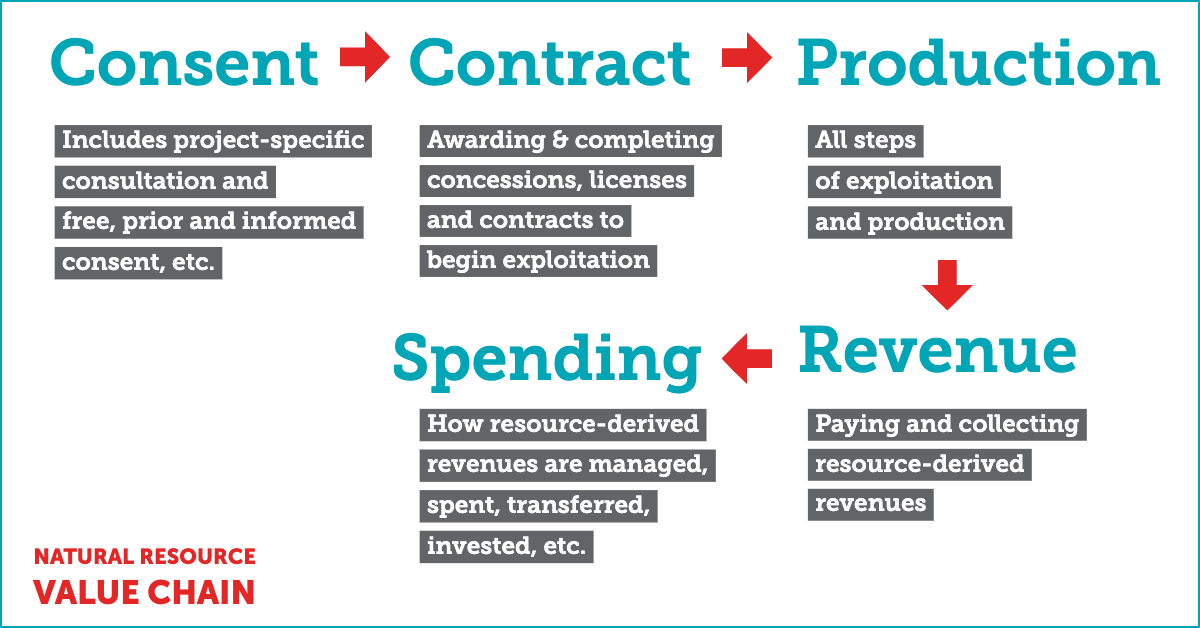

We have identified additional entry points in the country as well, always with an eye toward strengthening existing processes, adding value, and supporting the work of local organizations and government agencies, in line with R4D principles. Based upon steps in the natural resource value chain, LTRC can build community-specific open governance reforms that reduce corruption in the extractives sector while addressing gaps in the evidence base.

Globally, we engage and coordinate with other initiatives that are contributing to improved governance in the extractives sector. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the Executive Session on the Politics of Extractive Industries, Transparency International, among many others, are organizations with which we either coordinate, consult, or have representatives in our advisory board.

This blog is just the first in an upcoming series that will share details on our journey. We will also discuss our research projects in selected countries, as well as cross-country challenges and the ways in which they are being approached. Additionally, the series will provide insights on promoting learning and building a stronger evidence base for a new generation of programs and policies to fight against corruption in the extractives sector.