The challenges of abandoned mines in Nigeria

Colonial legacy and the burden of environmental justice

[Editor’s Note: In this piece, Olajide Adelana, a journalist in Nigeria, and Supriya Sadagopan, a program officer at R4D, explore the history of Nigeria’s lack of action in responding to health risks and challenges resulting from abandoned mines — with a particular focus on tin. Will Nigeria respond and prevent its past mistakes as the oil-dependent country turns again to mining for energy transition?]

Historically, mining has had a huge impact in the industrialization process around the world, particularly during the colonial era. Over time, the importance of selected minerals has varied, reflecting ever-changing demand. Local communities are feeling the lasting negative impacts of colonial mining even nowadays. And as it happened with the colonial government, the Nigerian state has been unable to provide clear solutions to the legacy of mining. This article explores the case of tin in historical perspective and how mining practices past and present still affect mining communities in Nigeria.

The importance of tin, then and now

The focus on important minerals needed for the energy transition has largely been on minerals like copper, lithium, cobalt. Tin has been typically neglected by comparison, but its demand is only going to increase with electric vehicle production. Thus, the International Tin Association estimates that global The primary purpose of tin is in soldering, where its use allows the flow of electrons (and thus anything electronic to have a battery charge). Tin has long been an important mineral, including in the days of the early industrial revolution, where it was used for packaging. This motivated colonial powers to seek tin deposits beyond their own countries.

Tin and mining in colonial times

Nigeria was a British colony from the mid-nineteenth century until 1960, when the country gained independence. However, the importance of mineral resources was not recognized until the British government scaled up tin production, which had previously been hand-mined by indigenous communities.

Following a 1903 survey to formally organize mining and set aside land tracts, the British government allowed foreign entities to establish official businesses in order to avoid inputting their own labor capital resources. As foreign companies began to take over, many local citizens lost their lands to the scaled tin production. Much of the royalties from the businesses for licensing and leasing were collected by the British Royal Niger Company, which had powers “in all the territory of the basin of the Niger.” To keep up with the increase in production, the area attracted both semi-skilled and skilled laborers from other areas and colonial countries.

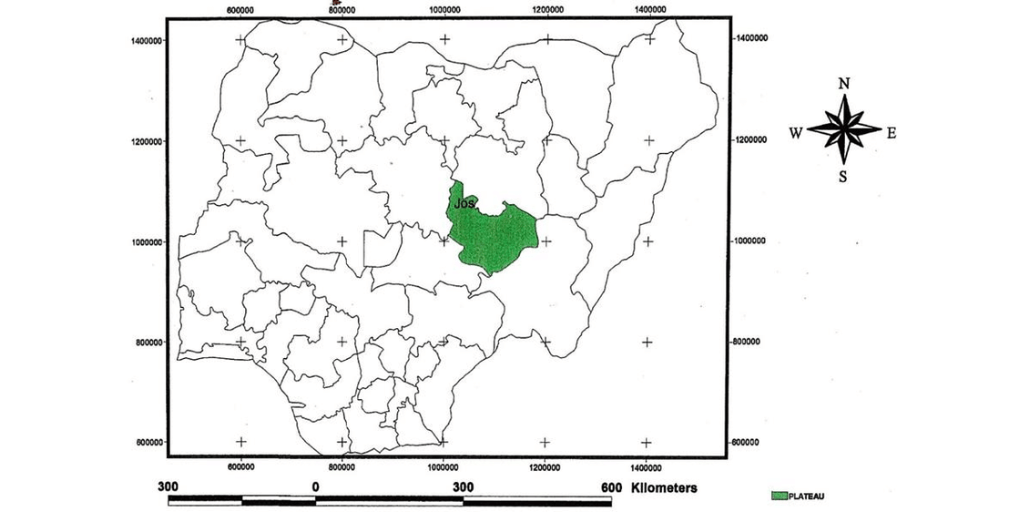

Tin production had a boom after the introduction of the railroad, which sped up the transport of tin to other major cities as well as ports. In just 10 years between 1901–1910, tin production increased from 50 to nearly 600 tons following the 373 to 893 square mile expansion of licensed area in the Jos plateau. Nigeria went from contributing 2.7% to 6.6% of the world’s tin production by 1914.

Image Source: Research Gate

Later, in the 1940s, Columbite (a tin by-product) production also increased, peaking in the 1950s. In parallel, coal production also went up with the advent of the railroad system as a primary source of fuel.

The decline of mining as a sector in Nigeria

By the mid-1900s, Nigeria was a major producer of tin, columbite, and coal. However, the Minerals Ordinance of 1946 still provided mineral ownership back to the British, stating that “the entire property in land and control of all minerals, and mineral oil in, under or upon any lands in Nigeria, and of all rivers, streams and water courses through Nigeria is and shall be vested in the Crown.”

This changed with the discovery of oil in 1956, which is Nigeria’s primary commodity even now. With the shift in focus to oil, mining activities for other minerals declined over time. Mining also decreased following the Nigerian Civil War, which led to the exodus of many foreign mining companies. The trend continued with the Indigenisation Decree of 1972, which limited the share ownership of foreign companies in mining to 40%, causing withdrawal of foreign investment.

Abandoned mines and environmental justice

Years after active mining, there remain abandoned and un-reclaimed mine sites posing physical and health hazards. As recently as 2010, the former Commissioner of Mineral Resources claimed that over 4,000 remaining ponds near mining activity show traces of radioactivity. These abandoned mines create an unsafe environment that include radioactivity, drowning, and air and water run-off that affect both agriculture and drinking water sources.

There were precautionary regulations introduced during the rise of mining in colonial times, but they were not enforced in practice. Prior to mining in Nigeria, the British empire had little experience with vast commercial mining, and the impacts of mining pollution on the environment until then had not yet been recorded.

The post-colonial Nigerian government has also struggled to establish and enforce environmental legislation for clean-up that would apply to current but most notably, to past mining communities. In fact, it is estimated that The 2007 Nigerian Minerals and Mining Act calls for mining companies to establish reserve funds for “environmental protection and mine rehabilitation, reclamation, and mine closure.” The law sets out provisions for both rehabilitation and reclamation in small-scale mining and mine leases moving forward, but fails to say anything about those abandoned generations ago.

The way forward

Local communities are still plagued by the hazards of abandoned mines from the 1900s. While Jos Plateau now has some vegetation, the remaining mining pools from tin mining cause

It is possible that Section 17 (2d) of Nigeria’s constitution “exploitation of human or natural resources in any form whatsoever for reasons, other than the good of the community” could be applied as basis for redress. Other avenues for action could include requesting a UN Special Rapporteur investigation or contacting the point person for business conduct in a multinational mining company. However, these means of contact are largely unfeasible due to a lack of information on citizen rights in these communities, and low literacy levels. Citizens are not empowered with the knowledge they deserve to demand accountability from these companies or their government.

Nigeria depends on mining for much of its income, and the role of governance in the mining sector will only become more important with the advent of the energy transition. Nigeria has an opportunity to change the way it addresses reclamation and abandoned mines of the past, making a difference for local communities in the area.