Raising the bar on reading

How a literacy program designed with “failing fast” in mind helps students in Sierra Leone succeed

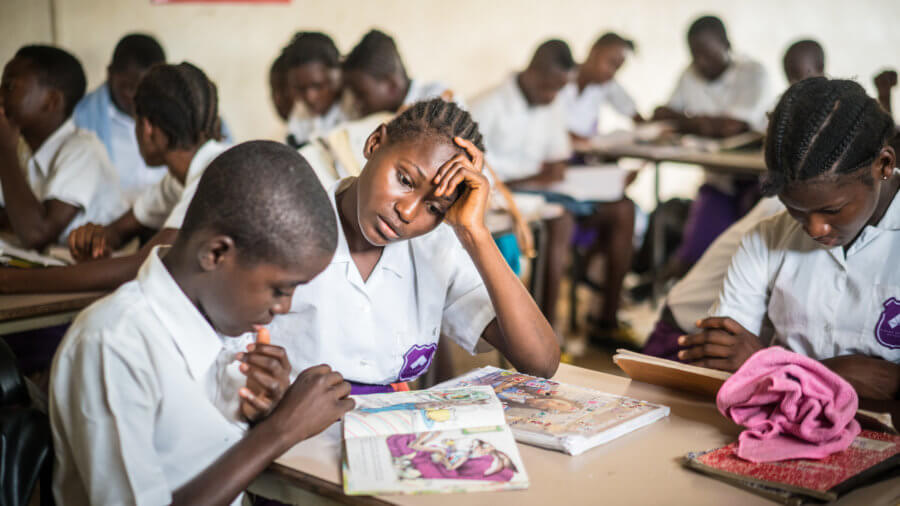

Despite the mud on her leather shoes, 12-year-old Haja Kamara doesn’t mind walking the mile to school each morning. She also doesn’t mind waking up at 5:30 to get ready for class, because Rising Academies isn’t like other schools. Where many classrooms in Sierra Leone are filled with students answering teachers with old fashioned rote memorization, Rising Academies encourages students to learn with a deeper level of understanding.

Students arrive for school at Rising Academy Network’s Regent School in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Photo © Results for Development/Michael Duff

“Learning is a skill,” Haja said, when asked why she prefers Rising Academies. And learning is central to Rising’s values, which are posted on the walls of each classroom: “We are Rising: We come to school every day, hungry to learn and thirsty for knowledge.”

Haja was fortunate to participate in an innovative reading program that the Rising Academy Network and Results for Development co-designed and piloted in 2016. And Haja wasn’t the only one who benefited from the program. In its first year, the program included 251 students and now it includes over 850 students. The program achieved more than reading success for students alone — the program also reinforced a culture of literacy in the school, and a culture of experimentation among Rising Academies staff. With a new approach to literacy, the Rising Academy Network is showing that rapid progress in reading is not only needed in Sierra Leone, but also achievable in the short term.

Haja Kamara, 12 years old, and Sorie Conteh, 14, are currently enrolled as a JSS2 student at Rising Academies Network’s Tengbeh Town school. Haja and Sorie participated in reading group as JSS1 students in 2017. Photo © Results for Development/Michael Duff

A new approach to education in Sierra Leone

In much of West Africa, rote memorization is a common teaching practice — but it doesn’t always lead to learning. Over 90 percent of young adult women in Sierra Leone who completed primary school still cannot read a simple sentence. Given the critical importance of literacy for better life outcomes — from improved health to overall economic growth — the lack of children in school with adequate reading skills must be addressed.

That was always Dr. Stephanie Dobrowolski’s goal in Sierra Leone. Originally a social intervention researcher in the U.K. and Canada, Stephanie moved to Sierra Leone to help launch a new type of school.

Stephanie explained that for many Sierra Leonean students, reading was solely about memorization. “You can’t even try to read a word you’re unfamiliar with, because you either know it or you don’t.”

Stephanie and her team realized that to improve the education of students in Sierra Leone, their model would need to do two things: 1) It would need to teach children how to learn, and 2) it would need to accelerate children’s learning to make up for lost time.

“If a kid is making one year of progress, but they’re starting five years behind, they will always stay five years behind,” Stephanie said. “We knew we had to do better.”

Rising set an ambitious target of increasing student literacy by an average of two grade levels for every year of schooling. By 2016, they were seeing progress with many students, but some were still struggling. Rising was looking for new ways to accelerate learning and to ensure that all students were succeeding when the team was first introduced to Results for Development.

Design, experimentation and iteration to drive literacy gains for struggling readers

Results for Development’s Evaluation and Adaptive Learning Team works alongside partners and employs a variety of monitoring and evaluation techniques to generate timely evidence and feedback to improve program design and implementation — and, ultimately, drive impact. In Sierra Leone over a 9-month period, Rising asked R4D to help them develop and test a literacy program that would support student growth and monitor progress over time while remaining easily adapted to and implemented in low-resource settings. The program would also need to eventually be scaled up without needing a large amount of central administration or sustainable resources.

“We’re not an organization that thinks we have it all figured out,” Stephanie said. The school had noted that students were entering the year with reading abilities far below their grade level, and previous students were still not improving fast enough. The benefit of an adaptive learning program meant that Rising could intervene in real time to help existing students, while planning for future students too.

Christopher Awolowo Reffell is a literacy program coordinator at Rising Academies Network’s Regent school in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Results for Development co-developed the literacy program at Rising Academies to help improve the reading skills of students through peer assessments, mentorship, and adaptive learning techniques. Photo © Results for Development/Michael Duff

Rising and R4D realized that monitoring student progress would require an innovative solution from their first in person meeting. There was no routine and consistent way to assess literacy progress across the schools. While subject matter testing occurred in school twice a term, the assessments varied (and thus, could not track progress over time) and they did not provide the rapid feedback that was needed to continually adjust the reading program.

Rising couldn’t do highly formal, hour-long sessions — they needed to fit the literacy assessment into a typical day without significant, regular disruption to existing classes. So, R4D recommended using a simple peer-to-peer assessment tool and training high performing JSS2 students (equivalent to U.S. eighth-graders) as the assessors, and the assessments were carried out every six weeks.

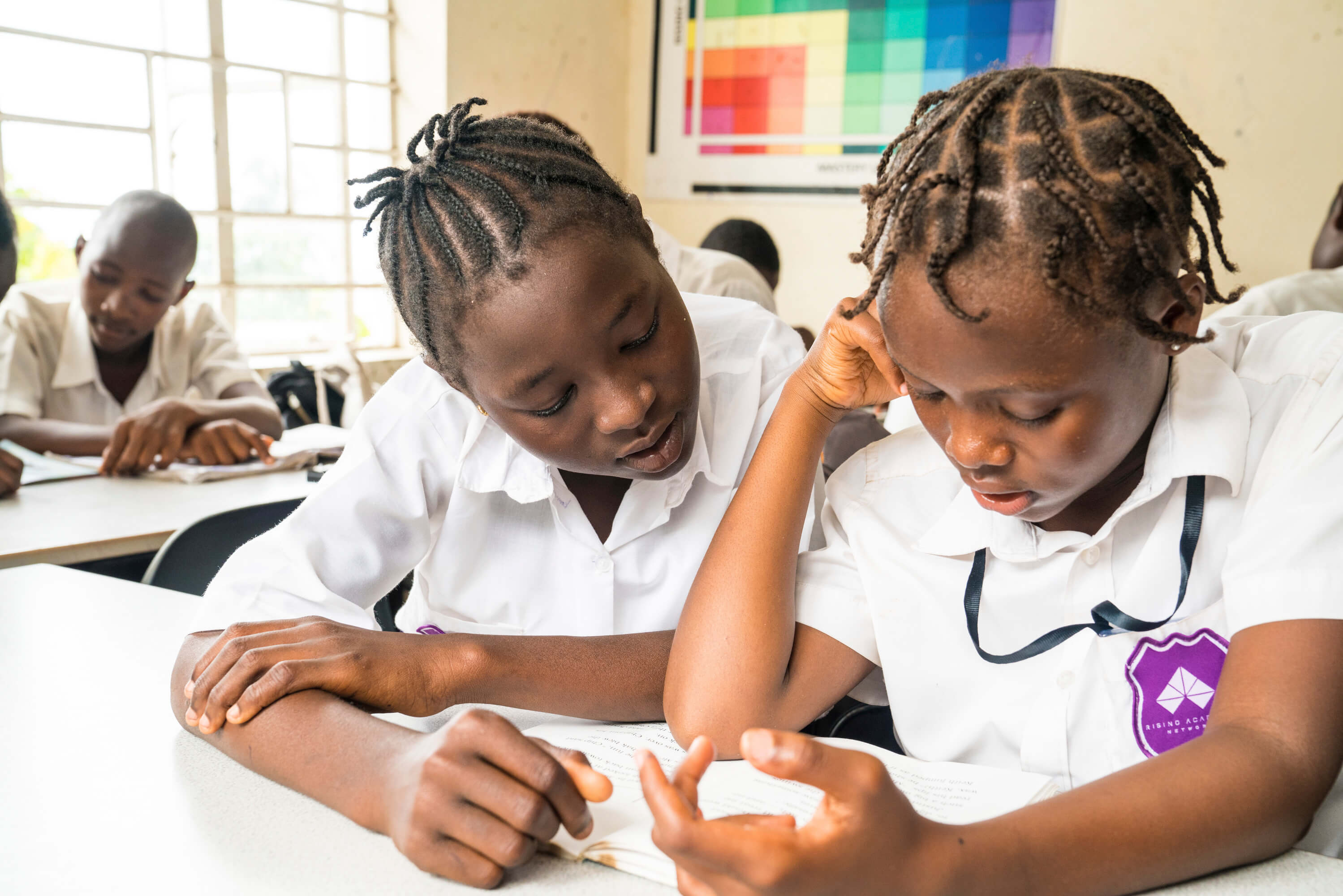

To help the struggling readers, R4D recommended a peer-tutoring reading club that would pair “Rising readers” (stronger readers) with “Helping readers” (struggling readers). Rising Readers and Helping Readers met separately twice a week to build skills, then in pairs twice a week and on Fridays to do a fun activity.

Mr. Jusu oversees reading club at Rising Academies Network’s Tengbeh Town school. JSS1 students work in pairs to help their peers improve literacy in a reading club initiated by Result for Development. Photo © Results for Development/Michael Duff

To keep students and teachers informed about reading gains and to create a motivational atmosphere, R4D recommended publishing a progress board that showed how students were doing — although they were only identified by an ID number. These three interventions formed the “ABCs” of RAN’s new approach to literacy: Assessment, Board and Club.

None of this was simple.

“Moving from an idea on paper to something that works in practice requires a lot of tweaking along the way,” said Morgan Benson, a program officer at R4D. “Testing critical assumptions can help you fail fast and make improvements.”

For example, in the program’s initial phase, the first version of the literacy assessment was too basic — even students who were struggling readers were passing with full marks. After adjusting the assessment to appropriately measure students’ reading skills, the R4D team noticed that there was still not as much interaction between peer reading pairs as desired. The team redesigned the program to include more training for helping readers.

The regular reading assessments provided an opportunity to rapidly get feedback on the literacy program at a small scale. R4D engaged Rising Academies staff in regular Learning Checks, where data on the literacy program were continuously shared and assessed. Over nine months, the two organizations used these Learning Checks to reflect on feedback from the data, experiences implementing the program and collaboratively making programmatic adjustments informed by the data and practice alike.

Scaling up for long-term success: More than just data

Rising Academies now has 10 schools in Sierra Leone, and manages 29 schools in Liberia as part of the Liberian Education Advancement Program (LEAP). Since the initial pilot, they have scaled up elements of the reading program across their network, including the use of literacy coordinators, reading clubs and peer-led assessments.

“The challenge for us now,” Stephanie said, “is not teaching one school or three schools, but a whole network of schools — with over 3,000 kids getting the same quality of education.”

In addition to the value of the literacy program to the students of the Rising Academies Network, the overall impact of the R4D partnership included an increased organizational culture of experimentation and learning. “The R4D approach helped give us the tools to assess and experiment with program design during and beyond implementation,” Stephanie said.

Students at Rising Academies are learning more than just the right way to pass exams — they are learning the life-long skill of how to learn. With the reading program, students are motivated to improve their own reading and teachers are equipped with the skills and tools to accelerate student progress.

Haja is living proof of this. According to literacy coordinator, Mustapha Jusu, when Haja Kamara first entered Rising Academies, “she was too shy to even stand and speak. But now, before you even ask a question in class, her hand is already up to answer.” Haja also helps her peer rising readers in reading club to sound out words and tackle larger words, and continues to excel.

Haja Kamara (left), 12 years old, and Madelyn Buannie (right), 10, are enrolled in Rising Academies Network’s Tengbeh Town school. Haja is helping Madelyn improve her reading skills in a reading club initiated by Result for Development. Photo © Results for Development/Michael Duff