How Nigeria’s NHIA Leadership Development Program is supporting the country’s UHC efforts

Across Nigeria’s health care landscape, dreams of equitable access collide with the harsh realities of fragmented systems, yet the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) stands as a beacon of resilience. Established in 1999, the NHIA, formerly the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), was born with a mandate to shield Nigerians from the crippling burden of out-of-pocket health payments and pave the way for Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

But for two decades, this vision wavered amid challenges. A voluntary participation policy led to low coverage rates — hovering within 10% for a population of over 200 million Nigerians — while leadership turnover (a staggering 12 CEOs in 20 years) triggered policy whiplash, eroding stakeholder trust and stalling progress. This high leadership turnover meant institutional knowledge evaporated with each transition, leaving a trail of disrupted strategies and unfulfilled promises.

In response to these challenges, the NHIA Leadership Development Program (NLDP) was born — a groundbreaking pilot launched in 2022 in partnership with Results for Development (R4D) and funded by the Gates Foundation (GF). What started as a focused response to the leadership crisis evolved into a transformative initiative that reshaped the very fabric of the organization and the entire ecosystem. The NHIA’s narrative transformed from a passive regulator to a proactive architect of UHC, a powerful testament to strategic foresight and collective determination.

The genesis: Addressing the leadership vacuum

The NLDP emerged from a thorough needs assessment carried out by NHIA and R4D. This investigation revealed glaring gaps; middle and senior managers in the health insurance sector were struggling with inadequate skills in strategic leadership, health care financing and public financial management. The high rate of leadership turnover led to a cycle of micro-transitions, undermining NHIA’s efforts to decentralize social health insurance and integrate fragmented systems.

The mission was clear: to break this cycle, NHIA needed leaders equipped with not just technical expertise but the adaptive skills to maneuver Nigeria’s complex health care landscape. Guided by the updated NHIA Act of 2022, which expanded NHIA’s mandate, the NLDP aligned with a bold three-point strategy focused on value reorientation, transparency and an accelerated drive towards UHC under then-CEO Prof. Mohammed Nasir Sambo.

The program unfolded in three phases — scoping, implementation and sustainability — which integrated both in-person and virtual training, coaching and mentoring. More than 350 participants from NHIA, its ecosystem and partners engaged in modules facilitated by leading institutions, such as the Enterprise Development Centre at Pan-Atlantic University (Lagos) on strategic organizational leadership and management; Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Centre (SPARC) in Nairobi on strategic health purchasing and benefit package design/rationalization; Ahmadu Bello University Business School in Zaria on essentials in health care leadership; and the Health Policy Research Group at the University of Nigeria in Enugu on health care financing and public financial management.

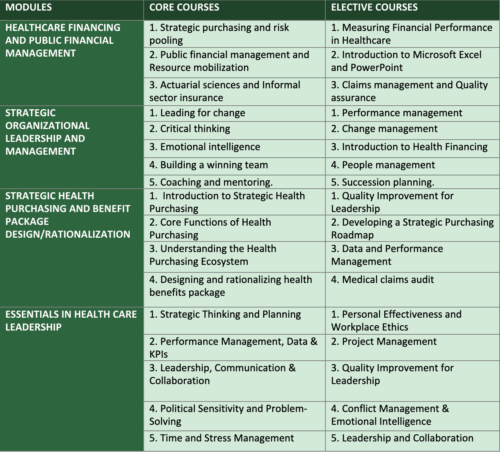

The courses participants were trained upon were identified from the needs assessment conducted at the conception phase of the training program. The courses are outlined in the table below:

The demographic mix was impressive. The selection includes 60% middle managers, 30% senior managers, and 10% state schemes officials, with a commendable 55% female representation from all six geopolitical zones in Nigeria. Engagement soared, boasting a remarkable 95% attendance rate, while pre- and post-module surveys captured participants’ growth in real-time.

The NLDP training adopted an action-learning community approach, focusing on common themes and challenges prioritized across different operational units of the NHIA, such as collaborative learning, collective problem-solving, building required skill sets and supporting one another to implement and scale up best practices.

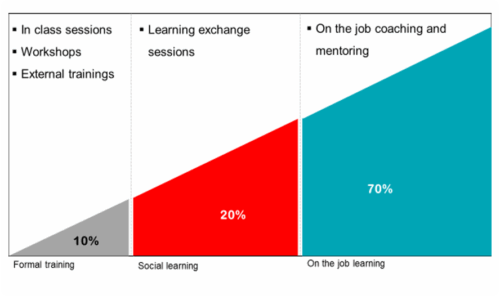

The program also showcased practical use of the 10-20-70 model, visualized below, for leadership development; it employed a hybrid learning methodology that included in-class training, virtual training, coaching and self-directed learning to accomplish a Personal Development Plan (PDP) tailored to each participant.

Source: Morgan McCall et al., 1990 learning concept at the Center for Creative Leadership in North Carolina.

The NLDP training adopted an action learning community approach, focusing on common themes/challenges prioritized across the different operational units of the NHIA; collaborative learning, collective problem-solving, building required skill sets and supporting one another to implement and scale up best practices.

The leadership training tried to ensure all participants were matched with experienced mentors and coaches within the training institutes to support their continued learning experiences. The on-the-job mentoring/coaching approach was expected to take up the bulk of participants’ time on the program (as much as 70%) with mentors sharing tacit knowledge with mentees; however, because of the participants’ regular day-to-day responsibilities, the coaching and mentoring approach did not have the expected impact. As the training program progressed, participants who met the criteria spent the rest of the training period continuing their usual work responsibilities or rotations while completing coursework and implementing the leadership challenge project.

At the end of the NHIA Leadership Development Program, participants were issued certificates, which bear the logos and seals of the participating institutions showing all offered courses.

A profound transformation from knowledge to impact

The true magic of the NLDP is its results. We evaluated the training program using the Kirkpatrick Model, which examines different aspect of effectiveness. The program excelled across all four evaluation levels: Reaction, Learning, Behavior and Results.

At Level 1 (Reaction), in terms of satisfaction, participants rated their experience 4.7 out of 5, celebrating the blend of practical and theoretical insights. For example, case studies on the integration of enrollees into the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) and an analysis of the health insurance fiscal space deeply resonated with participants, mirroring real challenges the NHIA faced. At Level 2 (Learning), 85% of participants reported significant knowledge gains in areas like Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and emotional intelligence.

A stronger transformation emerged at Levels 3 and 4. Some 78% of participants noted clearer job roles and heightened confidence in leading teams — critical for motivating cross-functional units amid UHC reforms.

“Before NLDP, policy shifts felt like whiplash; now, I lead with foresight, driving accountability within state social health insurances schemes,” said one zonal coordinator.

A chief executive of a state social health insurance scheme similarly reflected: “This is the first training we’ve had in a long time that truly impacts my leadership style, and I can see my staff becoming more open and friendly, sharing their thoughts with me in confidence.”

The NHIA saw a 25% increase in internal innovation proposals, a testament to newfound inspiration from initiatives like enrollment verification, benefits package design and rationalization, claims management, one pool system, actuarial analysis and strategic health purchasing across the health insurance ecosystem.

The NLDP also dismantled organizational silos. Consequences of high leadership turnover faded as institutional knowledge took root through transparent dashboards for performance tracking and adaptive learning cycles to ensure continuity. The program rebuilt trust and amplified NHIA’s ecosystem role of coordinating the “Health Insurance Under One Roof” (HIUOR) framework, which piloted coverage for millions through the donor-funded AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (ATM) program. It further expanded coverage of health insurance, reaching 10% of more than 200 million Nigerians.

The IUH blueprint is a legacy of capacity-building

If NLDP was the spark, the blueprint for the Institute of Universal Health (IUH) is its enduring flame. This blueprint, co-developed by the NLDP implementation committee and R4D, outlines IUH as NHIA’s crown jewel, a regional hub for excellence in health insurance regulation, research, technology and leadership.

The vision is ambitious: “To be the premier institution advancing universal health coverage through innovative leadership and sustainable health financing in Africa.” Its mission focuses on cultivating agile leaders through competency-based training across seven domains, including strategic purchasing and digital health, rooted in four pillars: Curriculum Excellence, Research and Innovation, Partnerships and Sustainability.

IUH’s strategic objectives align with UHC goals, including scaling the NLDP to more than 500 annual trainees, integrating Health Technology Assessment (HTA) into the curriculum, and fostering collaborations between public and private entities. The NHIA-led board will govern the program, guiding the development of in-house capacity and ensuring dedicated funding from Year 3 onward as it transitions from Gates Foundation funding.

The IUH blueprint ensures continuity, and by Year 5, it envisions evolving into the University of Universal Health, exporting Nigerian expertise continent-wide.

A call to sustained commitment

The NHIA’s shift from a fragmented array of voluntary schemes to a proactive leader in universal health coverage shows Nigeria’s resilience. The NLDP has not only trained leaders but has strengthened the NHIA itself, and the establishment of IUH will provide ongoing support for building capacity. With the NHIA Act paving the way for mandatory health coverage in 2026, reaching more than 50% enrollment by 2030 is within reach.

The current Director General is working hard to sustain progress in expanding coverage, improving strategic purchasing, mandating enrollment, strengthening claims verification and more. These efforts align with Nigeria’s priorities: better coordination across the health sector, saving lives, reducing out-of-pocket spending, revitalizing primary health care facilities, and lowering maternal, under-5 and neonatal deaths.

But this journey requires collective effort. Stakeholders, government agencies, donors and civil society all have a role to play by investing in IUH — and every leader the NLDP trains has the potential to bring health security to thousands more.