5 principles for building an innovative primary health care model

Strong primary health care (PHC) systems are vital to universal health coverage (UHC). The principle is clear and simple: if governments ensure essential health services are used — even in the most remote areas — population health will improve. Things get less clear, and significantly less simple, for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) thinking about how to implement this PHC Vision — especially in light of systemic problems at the point of health service delivery: lack of supplies and personnel, limited availability and the ability of individual health facilities to manage care for the population it serves.

As policymakers work to capitalize on global momentum for PHC, are there more immediate ways for countries to overcome some of the grassroots challenges?

When faced with this question, technical experts in Ghana commissioned an innovative service delivery model as a small-scale pilot in the country’s Volta Region — the Preferred Primary Provider (PPP) Networks. The pilot started in November 2017 and transitioned to a self-sustained practice in October 2019. During this period, it demonstrated the value network model can play in advancing UHC goals through improved collaboration among providers, referral coordination, availability of services and user experiences.

With the scale-up of this pilot already underway, policymakers in Ghana are considering a nationwide expansion. How did this small pilot get so much traction?

In this post, we will share:

But, first, let’s examine why the networks were commissioned in the first place.

Why primary provider networks were implemented in Ghana

Ghana has been reinforcing its PHC systems through its Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) strategy for a couple of decades now. The strategy has been effective in reaching communities, and serve approximately 18 million people as of 2016. The CHPS model has become an essential component of health service delivery, but individual CHPS still struggle to provide full set of PHC services, due to lack of infrastructure, medicine, supplies and human resource capacities (more details to follow in a forthcoming report). In response, Ghana piloted provider networks in the Volta region to test whether the PPP Networks model could address these challenges.

In a provider network, multiple individual facilities unite around one goal; for example, providing a comprehensive list of services to a defined population. This group is jointly accountable for clinical and financial outcomes, and quality of care for the population they serve.

There are different types of health networks in a health system. For example, in Australia’s “Layered on Top” model, one PHC organization incentivizes public health activities for multiple private providers. In Thailand’s “District Organization” model, district hospitals contract other facilities to provide a defined package of services appropriate to their level.

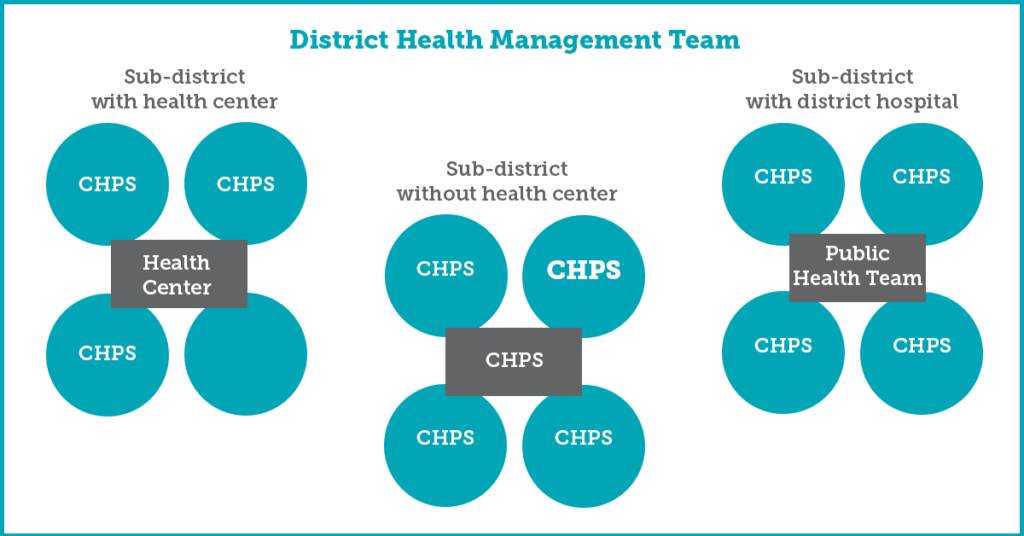

In Ghana, the network follows the Hub and Spokes model (pictured below) in which four to five small CHPS zones (spokes) link to a larger, more capacitated CHPS or Health Center (Hub) — forming a group practice of service delivery. The network unites individual providers to conduct joint activities to provide comprehensive care to patients, improves user experience and, at the same time, finds efficiency in using limited resources. It should be noted that the original concept of networks had a financial reform at its heart, as these networks were designed to support enrollment and service delivery practices under the capitation system for the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) — hence the word “preferred” in the title). However, the networks continued to function effectively even as a service delivery model after the suspension of capitation in 2017.

Figure 1: Illustrative Configuration of PPP Networks in Ghana

These technical and policy experts believe that the secret to the networks’ success in the Volta region is hidden in five key approaches taken during design and early implementation.

1. Ensure the network design fits the existing systems and structures

Some innovations seek to enact change by shocking and disrupting the system, but the masterminds behind the PPP Networks design took their chances on a model that fit the system, instead of disrupting it. They built networks that could operate seamlessly in the existing sub-national service delivery structure. For example, the Hub and Spoke model fits the practices of CHPS and health centers at the sub-district level like a glove. Moreover, governance of the networks is fully embedded in the existing sub-national administrative structures of GHS as well, with the District Health Management Committee and Regional Health Directorate providing stewardship and support to the network lead. The latter is an existing physician’s assistant or midwife in the “Hub” facility and mentors members from “spokes” on day-to-day implementation of network activities.

This perfect fit in the system had financial implications as well: after startup investments in training and supply support, the network runs on existing resources, with opportunities for efficiency savings, instead of costs, due to joint planning and implementation of public health activities.

The structure also creates a sense of familiarity and acceptability among new districts and regions. It is easy to envision and natural to implement — making the scale-up a straightforward process.

2. Harness collaboration, instead of competition, for user experiences

One of the key benefits of networks was its ability to strengthen interpersonal relationships amongst health workers, including their managers. This increased sense of collaboration and teamwork improved patient experiences and demonstrated tangible process improvement results. For example, coordinated referrals increased by about 43% in one district and by 28% in the other, within a year. In one district, the rate of NHIS claim rejections reduced by 69%.

Network members meet routinely and, when they don’t meet, remain in touch via WhatsApp groups to track referrals, ask questions and share knowledge. As a result, members feel more comfortable and empowered to reach out to more experienced colleagues for assistance when needed. They operate as teams and instead of competing for clients — this can significantly improve patient experience.

3. Address a well-documented and prioritized need

Right from its inception, the network model was driven by well-documented, and prioritized, health system needs — hence were rapidly endorsed by its practitioners. It all started with numerous independent evaluations of the capitation model, followed by a provided mapping exercise conducted in three regions of Ghana in 2015. All these reports highlighted that health facilities were struggling to provide necessary services on their own. This need was widely recognized among policymakers and the PPP Networks approach was recommended by experts reviewing NHIS performance in 2016.

4. Leave room to pivot and adapt, if necessary

While some innovations are “fixed” on the core concept of study, the Ghana PPP Networks were designed to allow flexibility and routine learning to inform ongoing implementation. This flexibility in the design enabled the networks to easily pivot from a financing model into a service delivery model in response to the suspension of capitation, as described above. Moreover, it enabled the technical team to bypass political sensitivities associated with this policy shift and re-introduce an adapted financial management component later. This model was more acceptable to network members — who, by then, had formed strong working relationships — and revealed financial efficiencies even with the existing fee-for-service payment models.

5. Invest in human capital

Last, but not the least, we should talk about the people who made these networks a success — network leads, district and regional health managers and, most importantly, health workers from member facilities. The primary investment in the PPP Networks was in people, or human capital — for their training, provision of supplies, follow-up visits for tools and the knowledge necessary to operate the new model successfully.

The design of this model prioritizes the leadership of network members and capacity building. The value of strong network leaders cannot be underestimated, especially when it comes to cultivating collaboration and reaching out to provide support and mentoring to colleagues in lower-level facilities. Staff in all facilities should be empowered to request support, apply newly-learned skills and be willing to share resources and experience with other members. Of similar importance is the time and effort invested in cultivating partnership with health managers. In the case of most successful network in Ghana’s PPP Networks, the district health directors championed — and continue to champion — the network model, mobilized political support and even additional funding to provide necessary infrastructure (e.g., laboratories, refurbished CHPS) for network members.

Where are they now?

Two years after the initial launch, the PPP Networks pilot has transitioned from pilot phase to a self-sustained service delivery model in the Volta region of Ghana. Networks now have capable health workers that feel more empowered to manage clinical cases, can organize care and improve upon administrative procedures (e.g., claim generation for the NHIS) at the sub-district level.

Two additional districts in Volta — Ho West and Adaklu — have already adopted the network approach and many more are expressing interest. National policy makers and the technical group are planning for the nation-wide scale-up.

These results would not be possible without Ghana’s Ministry of Health (MOH), National Health Insurance Scheme, the Ghana Health Service and technical partners from USAID’s Systems for Health project had designed the original model, supported implementation, tracked progress and documented learnings. Now the government has taken over stewardship of the networks, with technical support from USAID’s Health Systems Strengthening Accelerator.

We tried to tell the story of PPP Network the best we could, but you should also hear directly from the network members and managers in the video below.