Bright spots in a null RCT: Do-it-yourself efforts to improve maternal health

Part 4 of 4

[From 2013 to 2018, the Transparency for Development (T4D) project — a joint effort of the Ash Center at the Harvard Kennedy School and Results for Development — evaluated the effectiveness of a transparency and participation program that sought to improve maternal, newborn and child health. The result of the randomized controlled trial component of the evaluation was null — meaning that, on average, the program did not measurably improve the targeted health outcomes. At the same time, the wealth of qualitative information we collected allowed us to dig deeper into the stories behind these results, which revealed some surprising examples of specific, community-level success. This Bright Spots blog series will highlight and discuss those exceptions, not to contradict the RCT results, but to further contextualize them. Read the introductory post, the second post on facility supplies and infrastructure and the third post on access to health facilities.]

It’s an often (mis)quoted trope that more help comes to those who help themselves. Frequently, the quote is an attempt to justify cutting public or philanthropic aid. When used more generously, it can help convince individuals to be more self-reliant and responsible, or to argue for “programs of mutual support and self-sufficiency that break the cycle of economic dependency for low-income families and build more resilient communities from the ground up.”

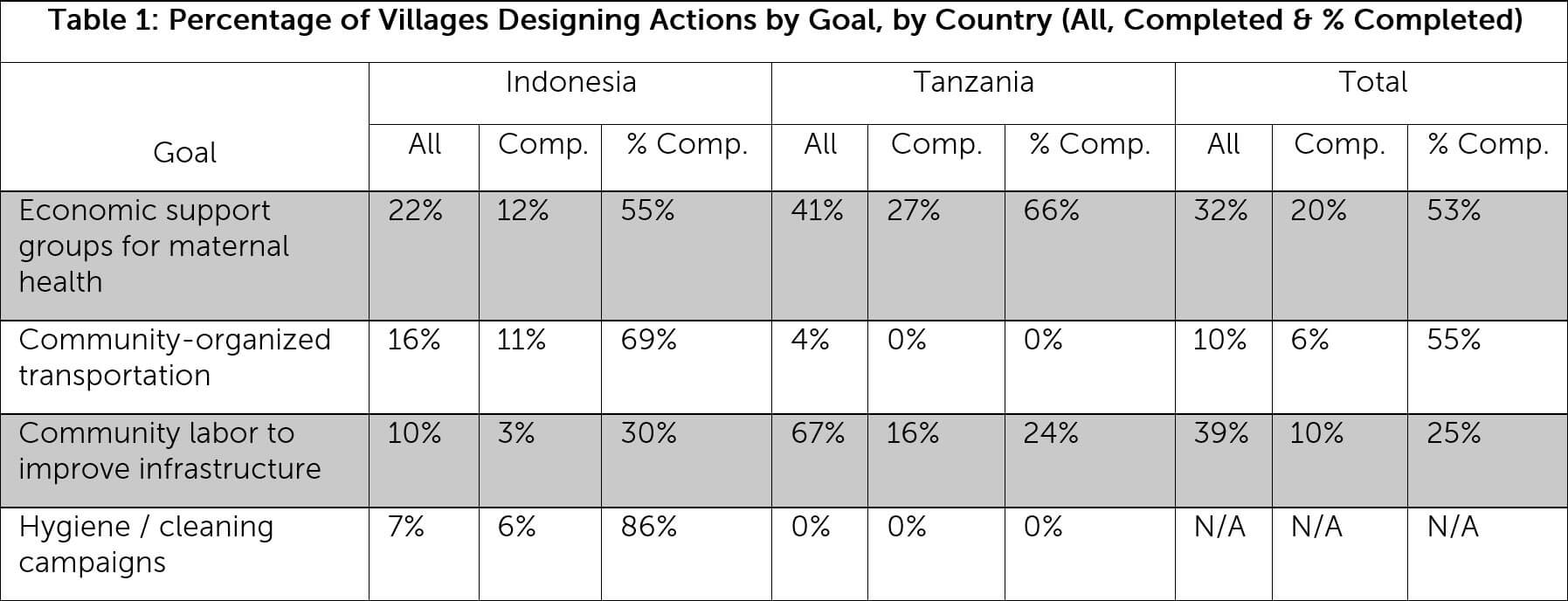

Several bright spots we saw in the T4D program were in the latter category, which we shorthanded to “self-help.” Table 1, excerpted from our forthcoming social action analysis, shows the percentage of villages in Indonesia and Tanzania that had self-help actions for a variety of goals, and the percentage of those actions that participants said they completed.

4 ways these self-help actions played out

Economic Support Groups

These groups were common in both countries, although more so in Tanzania. They usually took the form of maternity savings pools or more general entrepreneurial activities with a (sometimes vague) commitment to use resulting funds for maternal health. Previous public policies inspired these approaches, with many respondents explicitly citing Indonesia’s Tabungan Ibu Bersalin (Tabulin) savings program or Tanzania’s VICOBA community banking initiative.

In one successful Tanzanian case, a community representative explained that, “We thought starting our own [savings] groups would help in avoiding deaths of mothers and children.” They visited each sub-village and asked pregnant mothers and their families to contribute TSH 1,000 per month in exchange for membership in the group. By the end of the program just 90 days later, the facilitator reported a total of TSH 554,000 (US$240) in contributions, and that “two babies were helped by giving them TSH 200,000 to transport them to the district hospital for treatment.” Another TSH 100,000 was used to take a pregnant woman to give birth in a hospital.

Community-Organized Transportation

Over a quarter of communities designed an action to request an ambulance. In a smaller number of cases (and in some of the ambulance actions where no ambulance materialized), communities decided to organize their own transportation for mothers to give birth in facilities. This type of action was much more common in Indonesia than Tanzania, likely because of the much lower rates of car ownership in the Tanzanian communities.

One Indonesian community representative explained that “Many people in the community gave the excuse that they were not able to go to the health facility and give birth there due to lack of transportation.” To counter this problem, the representatives first listed ten villagers who they knew owned a car and asked them to volunteer. At least four people signed up, and the representatives announced the volunteers in the mosque after Friday prayers. They also spoke to pregnant mothers in their final trimester, to ensure they were aware of the cars if needed.

The service appears to have been taken up enthusiastically, with both the representatives, the village head, and the midwife praising the action. At the end of the program, T4D interviewed two car owners, who reported having taken five mothers to give birth in the facility.

Communal Labor to Improve Infrastructure

Rather than transportation, some communities chose to work on the bridges and roads needed to access facilities, or upgrade or build facilities, placenta pits, or waiting areas. These infrastructure actions were common in both countries, but Indonesian communities much more frequently asked the government to hire crews and fund the improvements. Tanzanian communities overwhelmingly chose to work on the infrastructure projects themselves, which is why Tanzania’s percentages are so much higher in the table above. You can read more about both types of infrastructure efforts in our previous post on access to health facilities.

Public Sanitation and Hygiene Campaigns

Many communities, especially in Indonesia, complained that their local health facility was so dirty that mothers would avoid going. And communities in both countries asked facility heads to clean up the facility and its surroundings; in Indonesia, seven communities went further and designed actions to clean up the area themselves.

One representative (and secretary of the local PKK women’s association) bluntly explained, “I was so sad looking at the Poskesdes’ [village health post] condition. It is dirty.” She and her fellows planned an action to first collect a small amount of money to purchase cleaning supplies. However, they quickly decided not to pursue the action as designed, with the representative explaining that “we feel sorry asking for money from the community.” Fortunately, the village already had a weekly aerobics class that took place on the facility grounds, so the representatives decided to leverage that class to clean the Poskesdes. According to reports, 20 people helped with one of the cleanings and as a result, both the midwife and the representatives considered the action a success. The secretary of a local farming group was also interviewed and reported that, at least, the first cleaning “worked well.”

Social Capital or Letting Government Off the Hook?

Like all of the blogs in this series, these stories are exceptions to a program with an overall lack of average impact. Many equally interesting stories in the categories above did not work as intended. Some Tanzanian entrepreneurial groups successfully generated additional income, but that income was not channeled into maternal health. One Indonesian group reported successfully creating a community transportation network, but when researchers interviewed the supposedly participating car owners, none of them had heard of the initiative. And several villages in both countries collected funds for the purposes of T4D, but then had those funds disappear when officials became involved. It is also a potential concern that so many community efforts sought to bypass the state altogether (trigger alert for anyone following the debate around community-driven development).

Still, no village entirely focused on self-help actions, and some of these self-help actions might have made it easier for representatives to work together on the other actions that did target the government or other duty-bearers. Many participants ended the program with quotes like:

The T4D program “helped us to be brave to visit formal institutions, and it strengthened relationships and friendliness among community members.”—An Indonesian community representative.

“Unity is strength; we have to work together.”—A Tanzanian community representative

On the whole, then, it was a bright spot that community members came together — especially given the growing recognition of the importance of social capital, “trust,” or “Ubuntu.” That is even one hypothesis we’re investigating further: whether communities with greater starting positions of social capital were more able to successfully implement the program. Stay tuned for that analysis, which we plan to publish in the coming months.