Bright spots in a null RCT: Social actions on the ground

Part 1 of 4

[From 2013 to 2018, the Transparency for Development (T4D) project — a joint effort of the Ash Center at the Harvard Kennedy School and Results for Development — evaluated the effectiveness of a transparency and participation program that sought to improve maternal, newborn and child health. The result of the randomized controlled trial component of the evaluation was null — meaning that, on average, the program did not measurably improve the targeted health outcomes. At the same time, the wealth of qualitative information we collected allowed us to dig deeper into the stories behind these results, which revealed some surprising examples of specific, community-level success. This Bright Spots blog series will highlight and discuss those exceptions, not to contradict the RCT results, but to further contextualize them.]

What can we learn from an intervention or project that doesn’t achieve its intended goal? In the context of T4D, which showed that the transparency and accountability interventions that participants designed had no impact on the goal of improving maternal and newborn health outcomes, how do the lessons learned from our quantitative data compare with what participants were reporting on the ground? Moreover, if these communities did claim successes — however small — do they matter in the grand scheme of things?

Central to the program that T4D implemented was encouraging participants to plan and undertake maternal and newborn health “social actions,” using an adapted community scorecard. This program was deliberately non-prescriptive, meaning that the specifics of what issues would be focused on and how they would be dealt with was left entirely to the communities. Such an approach opened up the possibility of innumerable courses of action to address the most pressing issues facing participants, all benefitting from their specialized and localized knowledge. Our data shows that this approach resonated with communities; by the end of the program in Indonesia and Tanzania, 1,139 social actions had been designed.

We hoped those actions would be able to instigate real improvements to how health care was delivered and experienced. However, our recent analysis revealed that the program did not have a statistically significant impact on either the content or utilization of health services. Despite enthusiastic engagement, few were able to translate these efforts into tangible outcomes.

Our qualitative data, however, paint a more complex picture of what was really happening on the ground. Health outcomes may not have improved, but, over the course of the program, many community members were undertaking real and innovative steps they hoped would improve their health care. So, what exactly does a “social action” look like? How did communities go about designing them? Moreover, what were the stories behind these so-called “positive” outcomes? These are some of the most frequent questions our team is asked when speaking with practitioners and researchers.

Communities design their social actions

The T4D program varied slightly by country, where we worked with local civil society partners during implementation (PATTIRO in Indonesia and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) in Tanzania). At a high level, however, the program played out the same: we held a series of six meetings, where a facilitator from our program partner would meet with community members in individual villages to discuss maternal and newborn health issues. After sharing information on key aspects of this care in the first meeting, the citizens taking part in the program (known as “community representatives”) would discuss the barriers they faced to delivering improvements. In the second meeting, these representatives would begin formulating the social actions they believed would address these barriers.

Community representatives planning their social actions in a Tanzanian village. Photo © Transparency for Development

In the next several blog posts in this series, we will do a deep dive into some of the types of actions that we observed as “bright spots” in the program. But, in this post, it is helpful to look at one village that pursued a broad range of actions — with mixed outcomes. In this Indonesian community, a particularly enthusiastic group of representatives designed seven actions — summarized in Table I (the average community across Indonesia and Tanzania planned five actions).

Table 1.

|

Indonesian Village Actions |

| Visit villagers who are too shy to go for a check-up at the health facility and encourage them to visit. |

| Educate the village on the importance of maternal, newborn, and child health. |

| Coordinate with key stakeholders to improve the quality service at the nearest health facility. |

| Submit a proposal to build a new health facility in the village. |

| Submit a proposal to repair the roads leading to the nearest health facility. |

| Re-start a local savings program to help community members pay for services at the health facility. |

| Educate the community on the importance of young children receiving immunizations. |

This village, like the overwhelming majority of participating communities (99.5%, by our count), chose to spearhead their approach with an education campaign to increase awareness and knowledge to improve community attitudes toward maternal and child health. Facility access was also an important issue for communities, with 71% designing at least one action to address it. In this instance, the community representatives decided that the rehabilitation of local roads was a priority, with one stating, “The midwife [finds it] difficult to go to the village.” However, access to the existing facility was not their only concern. As explained by the same representative, “[The village] is far from the health facility, so there should be a health facility in the village.”

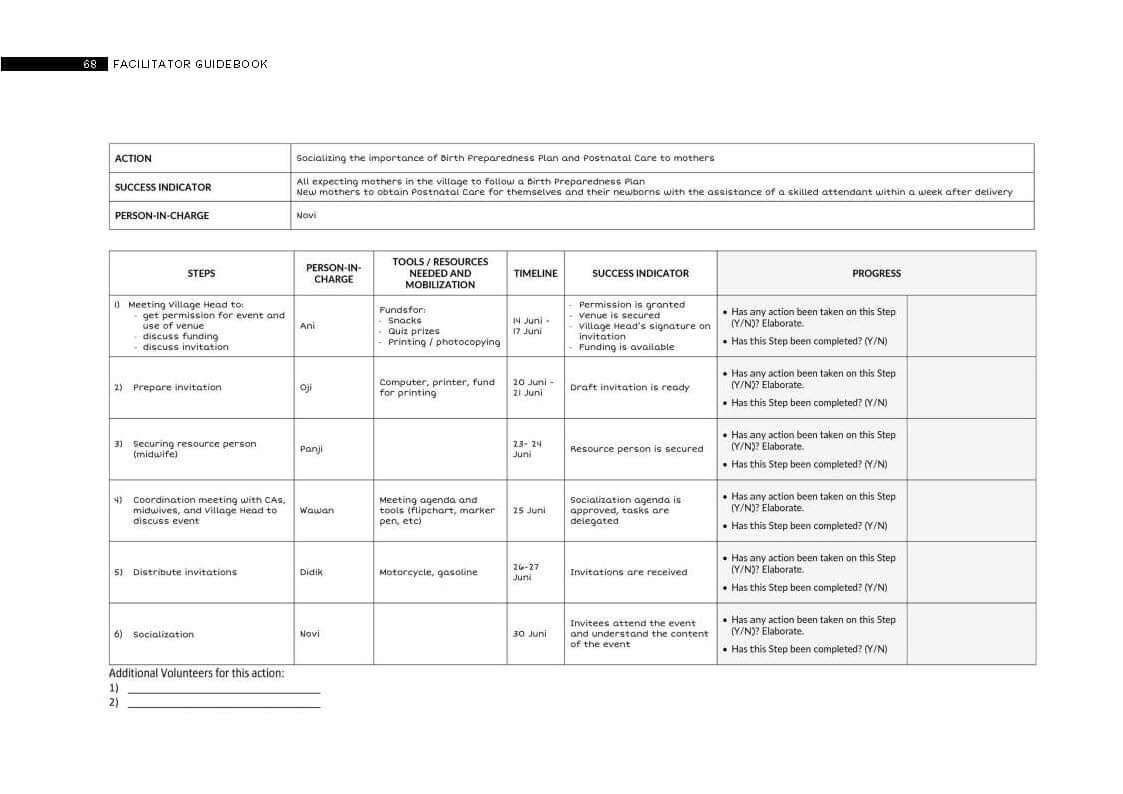

Image 2: An example of a written social action plan from our facilitator manuals.

Carrying out the action plans

After designing their social action plans, the group took these ideas to the wider community in order to gain feedback, secure buy-in, and allow others the chance to become involved. Our program facilitators then left things to the community, only checking in with the representatives at 30-, 60- and 90-day “follow-up meetings” to discuss their progress. With the program officially wrapping up as of the 90-day meeting, we also took the time to meet with key stakeholders, such as village leaders and health officials, to discuss how the program went.

Returning to our Indonesian case study, the representatives reported varying degrees of progress with their actions. They successfully managed to carry out an education campaign, for example, securing financial donations from the village and health facility heads to run an open meeting that was attended by 45 community members. The head of the health facility also agreed to make a personal appearance, volunteering himself as a “keynote speaker.” One member of the public who attended stated that the event was interesting and useful, but noted that they were already aware of the information that was communicated. Nevertheless, the community representatives were enthusiastically planning another education meeting by the end of the program.

Other actions made much less progress. Although their proposal for a new village health facility was received warmly by the village authorities, it quickly became apparent that the resources they needed did not exist. “Evidently,” explained one representative, “the village party supports the action […] but there is a problem with the fund source.” The head of a local health clinic did suggest renting a space for expecting mothers to stay when attending the nearest delivery services — even offering to partly fund the venture — but by their 90-day check-in, the representatives had been unable to find a suitable space. Despite the disappointments, the group reported a sense of achievement with their work and a determination to build on the small steps they had already taken. As stated by one member, “The representatives should stay solid, because this program is for the village development.”

This case study illustrates just one of the diverse stories experienced on the ground during the T4D study. Over the coming weeks, we will shine a spotlight on those efforts, telling the stories of their aspirations, frustrations, and sometimes surprising outcomes. We hope to leave readers with a broader picture of how the program was experienced by those who participated in it.

About the author

James Rasaiah is a program assistant for Transparency for Development and China Programs at the Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.