Decolonizing global health assistance through listening: Part 2

Case studies from Benin and Botswana

[Editor’s note: This is the second post in a series of blog sharing experiences from the African Collaborative for Health Financing Solutions (ACS) project’s work on supporting sub-Saharan African countries’ advancing their universal health coverage (UHC) agenda. This blog explores how continuous demand assessment, one of ACS’s guiding principles, was implemented in Benin and Botswana and the key lessons learned. Read the first post here.]

The African Collaborative for Health Financing Solution (ACS) is guided by five core functions that serve as the project’s guiding principles and constitute the foundation of all ACS activities at both country and regional levels. ACS believes that, by implementing activities guided by its core functions, it establishes the building blocks necessary for a sustainable and inclusive movement toward UHC in the countries where it operates.

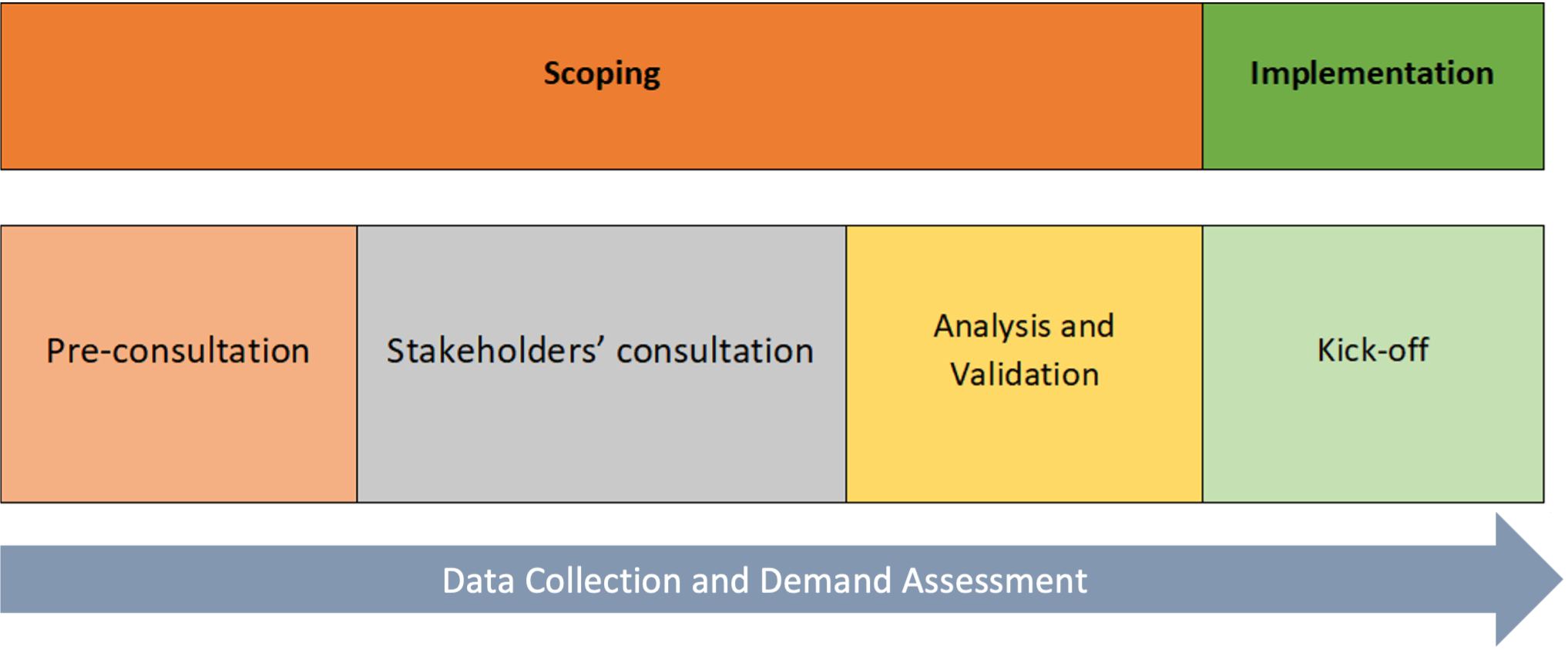

As one of ACS’s five core functions, Continuous Demand Assessment consists of continuously assessing country priorities and needs to advance progress toward country-specific UHC-focused objectives. This approach identifies country objectives by engaging a broad range of local, critical stakeholders to inform the development of ACS support strategies in each country and is structured as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Demand Assessment Roadmap

As a continuation of the blog, Decolonizing global health assistance through listening, where the ACS core function of “continuous demand assessment” was introduced, this blog seeks to illustrate continuous demand assessment in action by using ACS’s experiences in Benin and Botswana as case studies.

The Botswana Experience

In Botswana, ACS supports the Government in accelerating its progress towards UHC by ensuring sustainable financing of the country’s general health and HIV/AIDS response. Continuous demand assessment allowed ACS to gather the insights of several national stakeholders in an attempt to determine, inclusively and collaboratively, the national priorities relative to HIV/AIDS and Botswana’s movement towards UHC. The inquiry included a strong representation of national perspectives, including decision-makers, representatives of end-users, academics, and service deliverers. These stakeholders were consulted separately, which resulted in a diverse set of country priorities and assumptions.

The gathered priorities overwhelmingly highlighted the desire to focus on UHC; however, the funding was specifically for HIV/AIDS response activities. It became ACS’s responsibility to develop a solution that bridged the two needs. To achieve this, the project leveraged its strong relationships within the Ministry of Health to ensure the project’s focus remained aligned with the country’s priorities of moving towards UHC but through an HIV/AIDS lens.

The start of the project in Botswana required flexibility to ensure alignment with country priorities. The ACS team in Botswana was in constant communication with local actors to determine how their priorities could be incorporated into the implementation plan. Through continuous demand assessment, the project ensured that their activities supported the government in moving the country towards their goal of UHC. Due to the shift in focus and ACS’s partnership with both the MoHW and NAHPA, the ACS team in Botswana established itself as a bridge between the different governmental entities which contributed to their increased level of collaboration and moving in concert towards the country’s ultimate goal of UHC.

The Benin Experience

Based on learnings from the demand assessment in Botswana, the ACS project refined the tools prior to its implementation in Benin. This ensured that the team was able to collect the information more systematically and had the opportunity to meet a more diverse pool of stakeholders.

Moreover, ACS was able to partner up with the Centre de Recherche en Reproduction Humaine et en Démographie (CERRUHD), a well-established research organization in Benin that eased the project’s navigation within the health system. This alliance provided access to key informants who provided the team with invaluable information about how to better navigate the local environment and approach critical stakeholders. ACS also built upon the knowledge cultivated by the USAID funded project, Health Finance and Governance (HFG), that concluded as ACS was beginning. Learnings from HFG allowed the project to better frame the scoping exercise and create an official institutional transition.

The demand assessment exercise in Benin proved useful for ACS. Through the project’s effort to include stakeholders’ perspectives, it established a path for a symbiotic environment for meaningful collaboration among stakeholders and, simultaneously, established a relationship of trust between the project and stakeholders. The demand assessment exercise enabled ACS’s team in Benin to secure access to critical information in the health sector as well as to key stakeholders. As a result, ACS was perceived by stakeholders as an entity that supported them in attaining their national objectives.

5 things we’ve learned about the demand assessment process

In an effort to further synthesize lessons around demand assessment, ACS conducted a series of internal and external from stakeholders interviews to hear their perspectives. The learnings gathered from those interactions are summarized below.

1. Structure is key

Although the demand assessment exercise met its objectives in both countries, the process was challenging for the team. There is a need to create a platform that allows all stakeholders in a country to discuss, rank, and collectively agree on national priorities. As of now, the ACS project consults stakeholders separately which is time-consuming and reduces the time the project has to start implementing its activities.

Most critically, demand assessments are most successful when a pre-consultation exercise is included in the scoping phase during which a stakeholder analysis is performed. Although ACS did not do that in Botswana, the project learned from its experience and course-corrected its approach, and underwent a pre-consultation phase in Benin, which allowed the project to create new alliances and fortify previously established connections.

2. Deconstruct the concept

It is crucial to recognize that demand assessment needs to be deconstructed in each country context so that national stakeholders understand its meaning and embrace it with enthusiasm. All national stakeholders must understand the purpose of the exercise to ensure their full and meaningful participation.

Demand assessment must also be understood and embraced by project funders to avoid potential friction. The influence donors have in determining the projects’ pathways warrants their participation and consultation when identifying a country’s priorities.

3. Inclusion is essential

All legitimate stakeholders must be consulted to understand a country’s priorities, including government actors, the private sector, communities, donors, implementing partners, academics, as well as beneficiaries in a consistent way that considers each stakeholder group. Underrepresented voices, such as recipients of health services and the general population, have a critical role to play in demand assessment as successful policy design and implementation cannot be accomplished without them. Too often, it is forgotten that health is a holistic state of well-being and not just the absence of disease. Therefore, citizens have the right to having a voice in defining their country’s state of well-being.

Without diminishing its palpable necessity, it is also important to discuss the limits of inclusivity. When decisions must be made and the priorities of the different stakeholders are irreconcilable, the government’s position, by default, should take precedence as the way forward. In these circumstances, the role of a project should be to serve as a liaison of the people and ensure their perspectives are incorporated into the decisions of governmental actors.

4. Flexibility is a critical ingredient

Demand assessment consists of cataloging and prioritizing national stakeholders’ needs, and it should be expected that those needs might change from time to time. Change may also occur unexpectedly and lead to serious logistical challenges. For instance, in Benin, after ACS collected, prioritized, and validated the national priorities, the main governmental agency leading health insurance reform requested adjustments to ACS’s work plan. Because the changes were requested from the health authorities, the country team recognized the need to make the changes to the project activities in Benin and again validate them with stakeholders. Though this presented logistical challenges, the government became a stronger ally of the project, which enabled the country team to build trust and have access to critical information and stakeholders that supported the implementation of the project’s work plan activities.

5. Local partnerships support sustainability

Establishing CERRUHD as a strategic partner of the project in Benin served as a bridge between ACS and national stakeholders as well as a guide to navigating the country’s socio-economic and political context. CERRUHD’s proximity to national stakeholders also enabled ACS to reliably capture the dynamics within and across national stakeholder groups while simultaneously allowing ACS to establish the necessary structures to ensure that the country’s movement towards UHC will continue when the ACS project ends.

***

Even though continuous demand assessment was analyzed through the lens of a health systems intervention, it is replicable and applicable in other international development thematic areas. In Benin and Botswana, as well as in all other countries where ACS operates, continuous demand assessment allows ACS to adequately and contextually define its intervention and provide a holistic approach to implementing that intervention while taking into account the local realities. The approach has the ability to put national stakeholders at the center of the problem identification efforts and the formulation and implementation of solutions, building sustainability of the interventions and more self-reliance.