4 opportunities to enrich guidance for public-private engagement in health

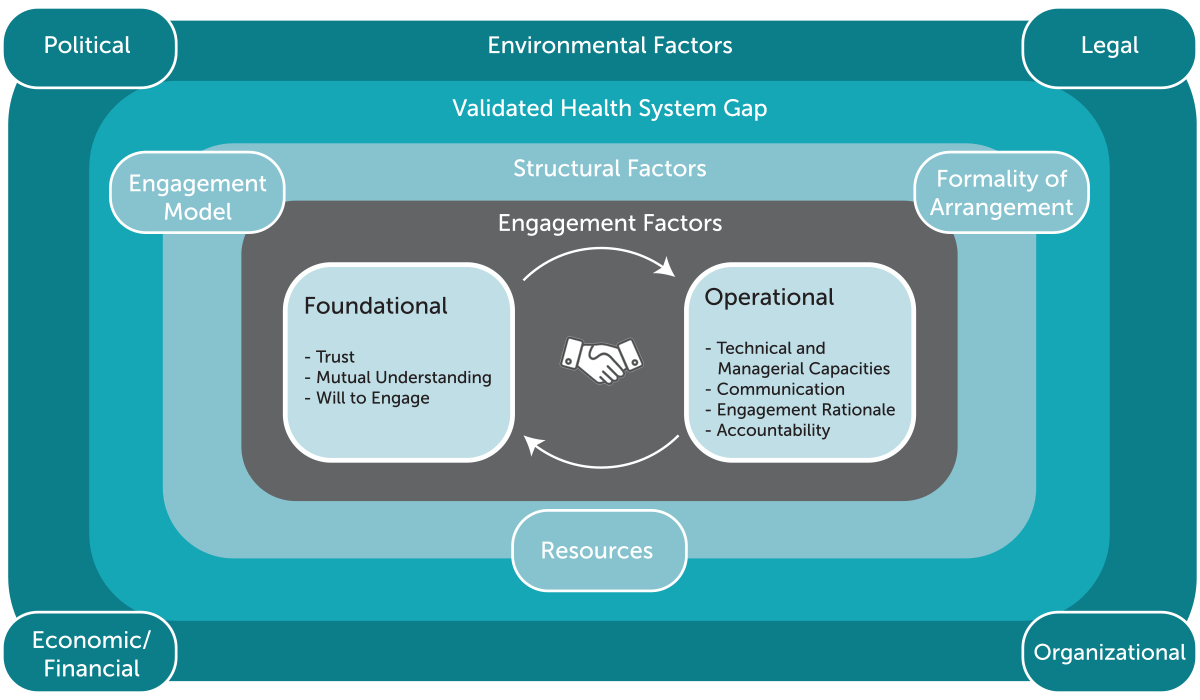

Many health system stakeholders are working to deepen public-private engagement (PPE) to help strengthen mixed health systems and improve their performance. As part of this blog series, we previously asserted the importance of considering PPE within a complex ecosystem of environmental, structural and engagement factors (Figure 1) that may help or hinder effective engagement. However, we anticipate stakeholders want more than this framing and expect they also seek guidance and information about whether or how to undertake PPE effectively.

Figure 1. Public-private sector ecosystem: factors for effective engagement

In this post, we take stock of available guidance for PPE in health in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), suggest ways to improve that guidance, and invite you to share your experiences and needs in this area.

To determine what’s out there in terms of PPE guidance for health, we searched the grey literature, produced mostly by development organizations and their implementing and research partners. We sought to answer several questions:

- What guidance exists for PPE in health, and does it reflect all of the ecosystem framework’s factors — environmental, structural and engagement?

- Who are existing resources meant for?

- What roles are suggested for actors other than government and private providers?

In addition to open Google searches, we conducted keyword and manual searches of 16 targeted websites maintained by global development institutions, health research and implementing partners, and conferences. This yielded nearly 150 resources, of which we selected 44 for in-depth review because they provided some combination of guidance, tools, training, and research compendia. From each resource, we extracted details into a database structured around the ecosystem framework.

Here are four highlights from what we learned:

First, while there are many resources for LMIC governments that want to engage more effectively with the private sector, none offer guidance for all elements of the PPE ecosystem framework.

We found 23 PPE tools, including five general engagement guides, ten analytical tools to inform general engagement, and eight more specialized tools (see Table for definitions and examples).

Figure 2. Definitions of PPE tool types

| Resource category | Definition | Example(s) |

| Engagement guide | Provides step-by-step instructions for engagement itself, often with embedded tools for supportive analysis | Private Health Policy Toolkit for Africa (World Bank 2013) |

| Analytical tool to inform general engagement | Provides detailed methodological guidance for broad health system analysis that generates an evidence base that can be used for PPE objectives and design, often including template data collection instruments | Assessment to Action: A Guide to Conducting Private Health Sector Assessments (SHOPS Plus 2014) |

| Specialized tool | Provides guidance for specific aspects of PPE and/or methods for targeted analysis | Assessing Health Provider Payment Systems: A Practice Guide for Countries Working Toward Universal Health Coverage (JLN 2015)

Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes Including Accreditation (ISQua 2015) |

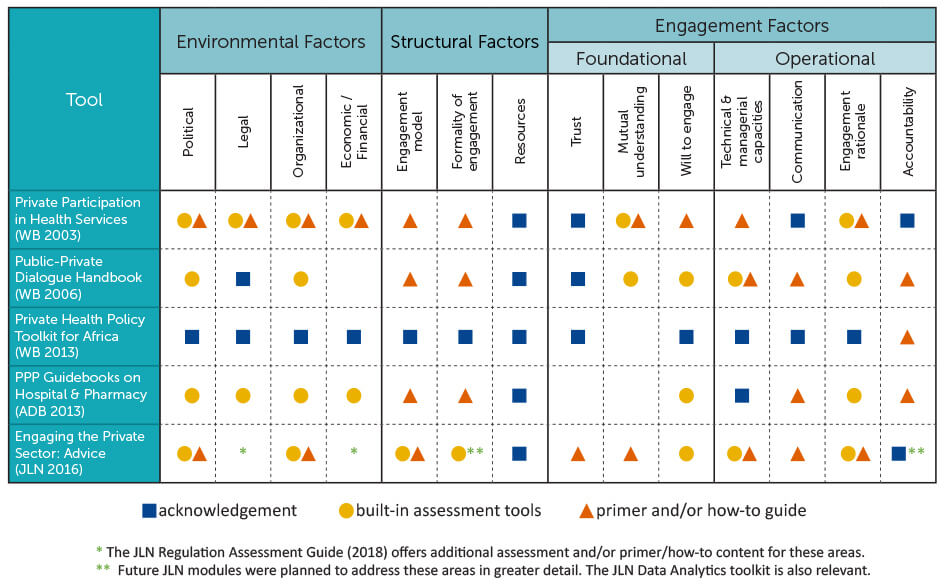

The engagement guides varied in how widely and deeply they addressed the ecosystem factors (see Figure 2). To our surprise, the only one to address all factors was the oldest: the World Bank’s seminal 2003 book, Private Participation in Health Services — a nearly 400-page reference volume that is in places more an encyclopedia than a pragmatic tool. The most recent, a 2016 guide from the Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage (JLN), is more “user-friendly”, rests on more and newer evidence from LMICs and is comparably thorough in some areas to the World Bank book though has yet to include modules on regulation and contracting. Important guidance can be taken from each, but it would be even better to have either an all-encompassing guide or one that systematically steers users to the right resources at the right time. The Bank’s 2013 toolkit took the latter approach but may not be practical or directive enough for the busy health official.

Figure 3. PPE engagement guides mapped to the ecosystem framework

Second, guidance is thinner for some of the ecosystem’s ‘engagement factors,’ than the foundational and operational qualities of public-private interactions

(Spoiler: the next blog in this series will discuss these in greater detail.) Between the engagement guides and analytical tools, there are ample resources for understanding the environmental and structural drivers of PPE, including widely conducted private health sector assessments. That said, more can be done to unpack what strategies make the most sense depending on how experienced country actors already are with PPE. Moreover, attention is less common to factors such as trust, capacity for engagement, and accountability. The reviewed resources typically acknowledged these as important, but only selectively offered proper how-to advice. For example, several engagement guides taught us how to design a stakeholder communication plan, but only the 2016 JLN guide gave us a few practical ideas for how to build trust. Those undertaking PPE would probably benefit from additional advice for how to get the engagement factors right.

Third (and related), it’s hard to determine the breadth of the awareness and use of existing tools.

The World Bank provides download counts for its publications, but neither they nor the JLN systematically track use of their tools (to be fair, this wouldn’t necessarily be easy). USAID’s SHOPS Plus project helpfully compiled numerous private health sector assessments, though accounts of the broader engagements they informed are harder to find. There may be value in more thoroughly assessing user needs and experiences, as well as connecting with existing (like the JLN Private Sector Engagement Collaborative or the Health Systems Global Private Sector in Health technical working group) or nurturing a global community of practice that can reliably connect decisionmakers to suitable resources. We noted a handful of PPE-focused training initiatives, including the recently launched Managing Markets for Health (MM4H) course, which can help to grow that community’s ranks.

Fourth, the grey literature documents or suggests numerous roles for third parties to PPE.

These include contributions to political mobilization, regulation (e.g., accreditation), capacity building, contract administration, funding, and facilitation of dialogue. In fact, many resources allude to the potential value of an ‘honest broker’ to help build trust between public and private actors. These roles might be played by professional and industry associations, civil society organizations, scholars, and external technical agencies. In LMICs, donors typically fund third parties, which may be why so many of the resources read like they were written more for global development technical advisors than for direct use by government officials or their private sector counterparts. (In fact, we only found one tool that was even nominally designed from the perspective of a private provider).

How does this help us move forward? At minimum, it validates our ongoing efforts to fill some of these gaps through the Strengthening Mixed Health Systems (SMHS) project, supported by Merck for Mothers. For example, our team is hard at work testing new ways to assess engagement factors in PPE and understand how they can improve to strengthen PPE over time. The findings also remind us to clearly define the intended users for any new resource, to ensure any guidance is practical and actionable, and to think carefully about how to get the information into the right hands. Finally, we noted (but did not systematically review) a range of training resources.

As we and our partners continue to map, research and design guidance framed around the PPE ecosystem, we also want to hear from you:

- What experience do you have using the resources we reviewed? In what ways did they serve you well? How could they have been more useful?

- Are there other resources you have found helpful in your PPE efforts?

- For which of the ecosystem factors would you value new tools or guidance?

We look forward to hearing your ideas. Please comment below!

The Strengthening Mixed Health Systems project is supported by funding from Merck, through Merck for Mothers, the company’s global initiative to help create a world where no woman has to die while giving life. Merck for Mothers is known as MSD for Mothers outside the United States and Canada.

Photo Credit © Eric Onyiego/USAID Kenya