Preliminary learnings from Nigeria’s Basic Health Care Provision Fund

Despite consistent efforts by government and its development partners, Nigeria continues to record minimal gains in health indicators, majority of which continue to fall short of national and international targets. More dismal is the fact that the highest contributors to morbidity and mortality particularly amongst the most vulnerable groups are health conditions that are either preventable or can be effectively managed at the primary health care (PHC) level. Nigeria remains the second largest contributor to maternal and child mortality in the world, losing an estimated 2,300 children and 145 women every day. Declines in maternal and under-5 mortality has been slower than comparable countries, such as including Kenya, Uganda, Senegal, and Tanzania, with Nigeria’s weak health financing system being a major driver of poor health outcomes.

The situation is further compounded by a constraint fiscal space, dwindling revenues from fledging global oil prices and persisting mismatch between domestic resource allocation and burden of disease. Expenditure from all tiers of government amounts to less than 6% of total government expenditure (a far cry from the Abuja Declaration) and less than 25% of total health spending in the country. This challenge has resulted in significant out-of-pocket spending (70%) among Nigerians, many of whom live on less than one dollar per day.

And while donor funding continues to bridge some gaps, this too remains unsustainable — particularly with project closeouts often requiring significant additional funding to preserve gains.

The National Health Act (NHAct 2014) presents a valuable opportunity to address these health financing challenges and promote equitable service utilization. It earmarks 1% of Consolidated Federal Revenue (CFR) for a Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), which makes supply- and demand-side investments for PHC.

The BHCPF helps to implement more equitable and efficient health care financing — to provide essential services to the most vulnerable members of the population.

To do this, the BHCPF utilizes two approaches to improve service delivery in at least one Primary Health Care Center (PHC) per ward in Nigeria: 1) through direct financial investments that funds critical upgrade for PHC infrastructure, improving availability of skill staff and assuring stock of medicines and health commodities; and 2) through the purchase of a Basic Minimum Package of Health Services (BMPHS) from PHC providers at no cost to Nigerians.

National-scale implementation of the BHCPF would create — for the first time in Nigeria — a sustainable mechanism to channel government expenditure to the primary health care system, with the goals of lowering out of pocket payments for critical services, increasing PHC utilization rates (especially among pregnant women and children under-5), and improving service readiness at the PHC level through increased operational financing.

Status of implementation

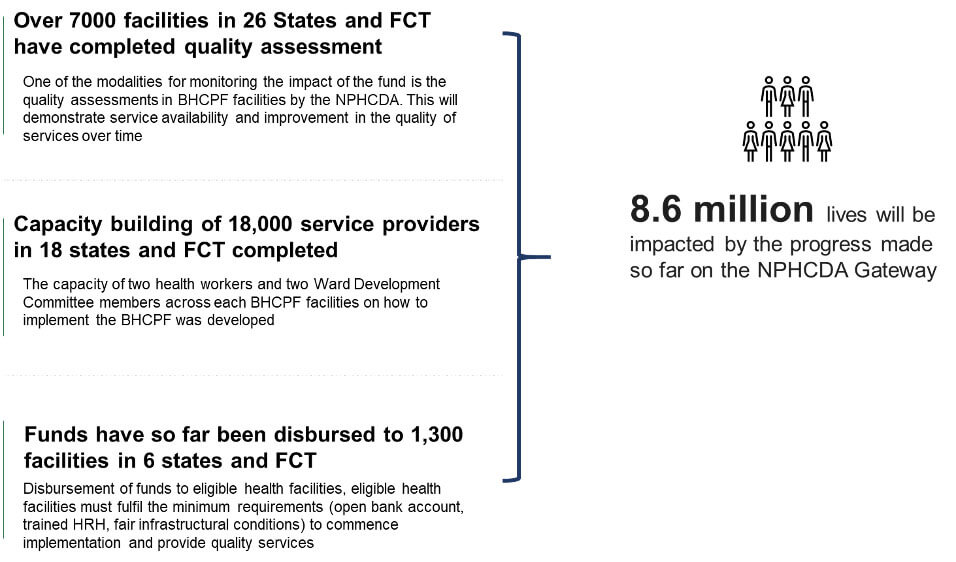

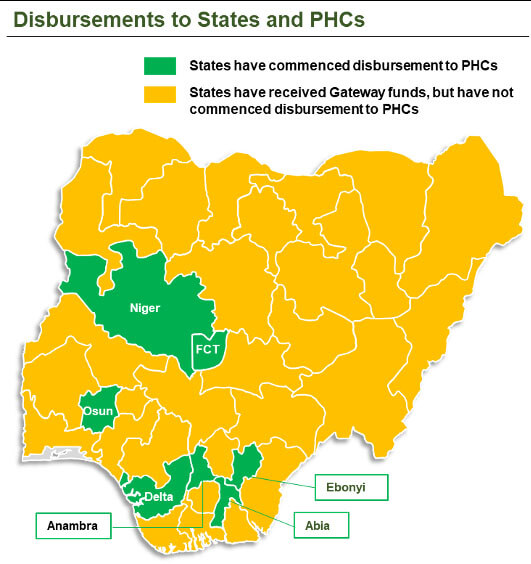

Funds have been disbursed to all 36 states, including the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). A total of 8.9 million Nigerians will be impacted by the funds that have been disbursed to 1,300 facilities across 5 states and FCT that have commenced implementation. The facilities have each received a sum of NGN601,500 to help in the provision of quality services to Nigerians.

Figure 1: Achievements recorded on the BHCPF

Quality Assessment: Baseline assessments of quality has been completed in 26 states and the FCT to determine the baseline condition of facilities and track improvement across 10 thematic areas. The quality assessment will show the impact of the BHCPF on the quality of care in facilities that will be benefiting from the fund.

Capacity building of health workers: The capacity of over 18,000 health workers and Ward Development Committee members across 4,600 facilities have been built on how to implement the BHCPF in 18 states and the FCT. These trainings will enable health workers to maximize the impact of the fund and also ensure the efficient use of resources. It will also empower community members to hold health workers accountable on how they utilize the fund.

Disbursements: So far, NGN 27.55 billion have been made available to the programme, and shared to the 3 implementing entities (NPHCDA, NHIS and EMT). NPHCDA has disbursed funds to all 36 States and the FCT.

Here are 5 things we’ve learned so far

Despite the challenges the BHCPF faces — including data management and communicating the benefits package at PHCs and facilities, among other issues — the much-required improvement in Nigeria’s health outcomes depends on the success of its implementation. Early results from facilities in Abia, Osun, Niger and Osun states that have started implementation have shown a 13% improvement in proportion of BHCPF health facilities with minimum required health workers (at least 5 health workers, including 2 midwives) when compared to the baseline.

Below, we share a few preliminary learnings from the implementation of the BHCPF.

- There is room to improve coordination among all stakeholders. To achieve the goals and objectives of the BHCPF, there needs to be a stronger alignment and adherence to extant laws guiding implementation among key implementing entities and stakeholders. This is important in ensuring all relevant stakeholders responsible for the implementation of the Gateways are aligned in attaining the goals of the BHCPF.

- The BHCPF requires more resources for large-scale implementation. The present resources available to fund the BMPHS cannot cater to all Nigerians and as such the NHIS needs to prioritize the poor and vulnerable.

- Implementation should have started with a pilot program before gradually scaling up. A pilot program would have provided the country with valuable lessons and insights before scaling up.

- There is need to develop a robust ICT system that integrates all the data from program implementation. This is important because 9,000 facilities will be enlisted for the program at full implementation and managing program implementation data manually will not be sustainable.

- Implementation should be phased. At the current level of fiscal space for BHCPF, the benefits package should be streamlined to be only for the vulnerable population. The vulnerable population are at a disadvantage when it comes to assessing care and if health inequities are to be addressed they should be prioritized.

It is too early to measure the impact on service utilization, but based on evidence that availability of quality care without significant financial barriers are massive drivers of service utilization (by those in need), the BHCPF will increase service utilization and furthermore, decentralize managerial structures engineered through the use of Direct Facility Financing to enable PHC systems respond to community needs in an agile manner.

Photo © Kate Holt, JHPIEGO/MCSP