State Capture Matters: Challenging corruption and a new dataset

Editor’s note: The following blog is part of the Governance Action Hub initiatives to use evidence and data for action in one of its core themes: state capture and anticorruption. The blog is a companion to the article “State Capture Matters” and the associated index dataset, by our senior fellow, Daniel Kaufmann.

At the presidential palace of a large country, a pair of journalists were interviewing the chef. They asked him how he managed to adjust to the shifting culinary tastes of so many heads of state during his long tenure at the palace. Unfazed, he supposedly retorted that menus didn’t differ that much, since “presidents come and go, but the list of dinner guests doesn’t change.”

What are we talking about?

The story of the palace chef vividly illustrates the contrast between the more systemic and political concept of state capture and the conventional and transactional understanding of corruption. The decades-old definition of corruption, understood as “the abuse of public office for private gain,” is still dominant, with minor tweaks. And for the longest time, the traditional approach to corruption has focused on the transactional ways corrupt actors get around the existing rules of the game through illegal acts, such as bribing public officials.

The notion of “state capture,” by contrast, refers to the undue influence by members or groups in the economic and political elite in shaping the rules of the game: morphing and distorting the laws, policies, regulations and institutions of the state to their own advantage at the expense of society. The notion of state capture is in fact more akin to the idea of “privatization of the rules of the game” by elite actors than any alleged extortion or abuse by a public officer.

State capture is thus likely much more insidious and costly than administrative corruption. Its societal implications, the way we measure and address it, are different to the way we have traditionally approached corruption. Making it even more troubling, state capture can be legal. This is because captors exert their oversized and undue influence to make the otherwise extra-legal or unethical perfectly legal in the settings where they operate, thus avoiding legal jeopardy.

When we advanced the notion of state capture a quarter of a century ago (with Joel Hellman), the initial focus was on powerful non-state actors who unduly influenced or “captured” the state. The focus and measurement at the time relied on a survey of post-socialist economies in transition. Since then, many scholars have considered actors within the state as potential captors as well, including state leaders and political parties. And from the study of country cases over the years, be they in countries like Russia, South Africa, Brazil or the United States, it is also clear that very powerful non-state and state actors often collude in capturing the rules of the game.

Can state capture be measured?

An “advantage” enjoyed over the decades by researchers and analysts of corruption has been in the ability and persistence in measuring the phenomenon, even if imperfectly. Many periodic and individual measures of corruption exist, as well as a couple of “polls of polls” that aggregate across individual measures, such as the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) by Transparency International and the Control of Corruption indicator in the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI, produced jointly by Aart Kraay of the World Bank and myself).

By contrast, efforts to measure state capture have been focused on a few countries at the time, or at most, on a region (e.g., post-socialist countries), and have not been consistently applied over time. There has not been an empirical initiative measuring the extent of state capture around the globe providing a comparable series across time and space. In part, this is due to the inherent difficulty in measuring state capture: it is a particularly complex, multi-faceted challenge, often taking place in opaque corridors of power.

Mindful of both the empirical gap in the field, as well as of the measurement pitfalls, I embarked on a first effort to provide such comparable state capture index, relying on carefully selected variables serving as proxies of elements of state capture, which were drawn from a few sources that have published data for decades. The details of this exploration are spelled out in the article “State Capture Matters.” In it, I first review the evolution of research on state capture, and then describe the development of a global State Capture Index. The Index measures the evolution of state capture and its components in 172 countries over almost three decades. The dataset is also available for download, with the appropriate explanations and caveats, since margins of error apply.

What does the State Capture Index tell us?

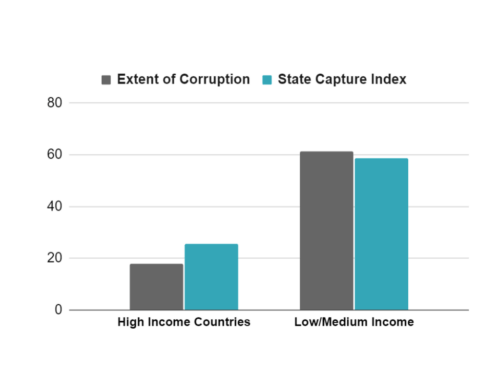

The results point to substantial differences between traditional measures of corruption and those of state capture across many countries around the world. As shown in the figure below for a recent period, in high-income economies there is a relatively higher prevalence of state capture compared with traditional corruption, contrasting the averages in low- and medium-income countries.

Thus, for advanced economies, traditional measures of corruption appear to have underestimated the extent of the broader and more political governance challenge of state capture. For some OECD economies, such as the United States, Britain, Chile, and Hungary, the gap between (higher levels of) state capture and traditional corruption is particularly wide.

Extent of (traditional) Corruption (WGI) vs. State Capture Index (SCI) for High Income and Low/Medium Income Countries (2020-2022)

Data sources: WGI for extent of corruption; SCI for state capture; World Bank for income group classification.

Further, by tracing countries over the decades, the evidence suggests that the extent of state capture has changed substantially over time for many countries. There have been large increases in many countries, declines in others, and reversals in both directions as well.

Why measure state capture?

Among other compelling reasons, the results suggest the importance of periodic measurement for “early warning” purposes in many countries at potential risk. By identifying countries at early stages of state capture, prevention strategies to avoid a possible descent into full capture could be put in place. Such prevention strategies are more likely to be effective –and less costly—than belated effort once fuller capture has taken hold, which is much harder to reverse. Periodic monitoring, early warning detection and design of prevention strategies make a compelling case for investing in the generation and analysis of data on state capture.

To inform the design of prevention action programs, the measures provided in the state capture index can help point to where the main vulnerabilities may reside: is it in their captured rule of law institutions, or in the policy and political arena? Or is the overall governance environment particularly weak and enabling state capture? The components of the new index shed light on these questions and indicate that countries with similar levels of state capture may in fact suffer from a capture of very different types of institutions, as well as by different types of captors.

Consequently, the institutional and policy responses to counter state capture will naturally vary from country to country, depending on the strengths and vulnerabilities and overall political economy and governance environment. The focus of concrete strategies to address state capture risks in each case, based on evidence, would tend to differ in important respects from the traditional anti-corruption efforts of the past.

From research to reality — and to action

As the anecdote of the chef hinted, the focus on state capture is not academic, but real. Prominent cases of state capture around the world abound, with dire consequences. The Lava Jato (Car Wash) scandal in Brazil tainted industry and political leaders in the region and resulting in a fall in major infrastructure investments. And tellingly, the Gupta-gate scandal in South Africa, where a powerful family colluded with a former president, was later formally investigated as a case of State Capture. In fact, in our testimony before the Commission of Inquiry into State Capture, we were asked about the antecedents of the notion and experiences from other countries into the subject.

Ahead, preventive action will be key. With appropriate caution, the presented approach and data on state capture could serve as an important input to country strategies and action programs. To be most effective, it would need to be complemented by a dedicated in-country diagnostic in a participatory multi-stakeholder initiative, with audacity and rigor, such as efforts being supported by the Governance Action Hub.