Toolkit Home / Topic 04: How to design and facilitate a Collaborative Learning Network

Topic 04

Sign up for our monthly newsletter R4D Insights to get the latest tools, resources, and news in global development.

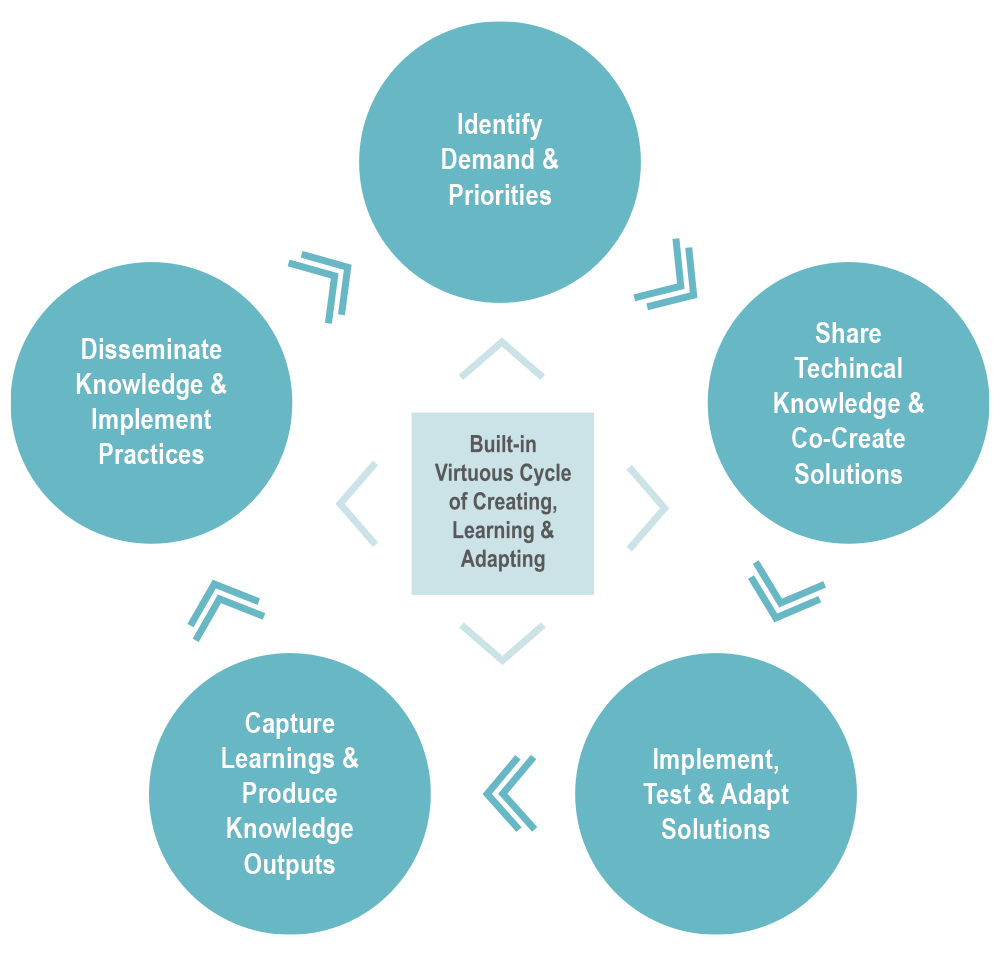

The Collaborative Learning approach is a systematic cycle of learning among peers that is iterative and adaptive. Collaborative Learning starts with identifying and building a learning community among a group of peers, identifying common areas of challenge, and jointly setting a learning agenda. Through a systematic process of technical framing that brings together the relevant evidence and country experience, drawn from global examples and community members’ tacit knowledge, the learning community sets off on a structured process of experience-sharing, accompaniment, collaborative problem-solving, and co-creation of solutions and new knowledge.

Technical facilitators support the community to capture the learning in practical and accessible formats as global public goods that others can also use. Members of the community are encouraged and motivated to adapt and apply the learning in their unique contexts, share their implementation progress and challenges, and seek support through regular feedback loops within the learning community. This virtuous cycle of sharing-learning-adapting can be facilitated through rapid-cycle virtual learning exchanges of six months, or through more in-depth learning collaboratives that might span 2–3 years.

As highlighted in the Collaborative Learning Network (CLN) theory of change (see Learning Topic 3), the achievement of systems-level and field-building outcomes is driven by a strong learning community. Over the past decade of designing, facilitating, and managing a variety of Collaborative Learning Networks, R4D has identified 10 essential ingredients to optimize their effectiveness and potential for impact.

Having a sharp vision, clear call to action, and value proposition is essential to getting a CLN started and nurturing it through its evolution.

CLNs are founded on the importance of social interaction, recognizing that relationships, trust, connectedness, collaboration, cooperation, and collective action are critical elements of adult learning (Provan et al., Interorganizational Networks at the Network Level: A Review of the Empirical Literature on Whole Networks, J. of Management, 2007). CLNs need to create inclusive, safe spaces that provide both formal and informal opportunities for people to network and build ties, network members and all stakeholders in between. In a CLN, every participant is recognized as both a learner and a sharer, who possesses a learning mind-set and valued experience and expertise to share. Fostering informal connections is important for building the friendships and relationships of trust that enable sharing, learning and collaboration with one another. A sense of healthy competition can even form through community, when participants motivate one another to advance their goals.

A clear principle of all effective CLNs is that members must be at the center of the network’s design. CLNs are most successful when members have enthusiastically opted into the network and feel a sense of shared purpose and ownership over the network’s health and effectiveness. When members play a role in establishing the network from the beginning, as well as set their own agendas for ongoing Collaborative Learning, the network’s priority issues and activities are relevant to them, and they can be certain the time they devote to network activities will be well-spent and support their day-to-day work. Engaged collaborative learners also feel a responsibility for one another’s learning as well as their own. Thus, the success of one learner supports the success of other learners. (Laal and Ghodsi 2011, Benefits of Collaborative Learning).

In all CLNs, participants exhibit varying levels of engagement. Some are highly engaged, some may have less time to give or care only about a focused set of priorities, and other participants may have minimal engagement. The Fito Network, a network of social impact networks, uses the analogy of a network as a ship, where some participants that are passengers (who are along for the ride, to touch the surface and mingle with others), some that are deep-divers (who want to go deep, engage in focused ways) and some that are crew members (who help steer the ship and have a bit more time to give). CLN managers and facilitators must understand the priorities of different participants and their preference for engagement and to identify meaningful and ‘right-sized’ ways for them to participate.

CLNs also need methods for iteratively engaging and continuously assessing evolving member needs and demand for support to ensure the CLN is timely and responsive to member priorities. For network managers and facilitators, this requires 1) developing strong, trusting relationships with members, 2) establishing systems for capturing areas of shared interest and facilitating a process to prioritize topics that multiple stakeholders want to address, and 3) building “country/member intelligence” to inform the design and implementation of network activities.

Strategic identification of the “right” change agents and their active engagement in the CLN are crucial to the CLN theory of change. CLN members need to be well-positioned and capable of integrating local experience and priorities into the agenda-setting process for the network, they need to be able to actively participate in CLN offerings both as learners and sharers, and they need to be able to share, adapt and apply learnings in their “home” context. One of the most challenging aspects of a CLN is to balance an open and inclusive membership model while ensuring that members have the influence and responsibility to adapt and implement the learning. Barriers to involving the “right” stakeholders can sometimes be political (where participation is based more on political motives than an objective determination of fit) or based on bandwidth and availability (already-busy key change agents may have limited ability to actively engage).

One key method used to identify CLN members is an expression of interest (EOI) process to match member demand with available learning opportunities. Members are invited to submit short written EOIs to articulate their interest in the learning opportunity, their objectives for participating, and who are the “right” participants to involve. The EOI process is designed to ensure a learning team with the optimal stakeholder composition is assembled, the learning opportunity is timely and relevant for the country, and the country demand is genuine.

Members opting in through a written EOI or other mechanisms for expressing demand is a necessary, but not sufficient step to ensure that engagement moves beyond learning to action. To drive local change, it is equally important that network members have the authority to make decisions, commit resources, and advance real progress within their contexts. As new members join, strong communication about the network’s purposes can support an adequate vetting and onboarding process to ensure that participants will not only attend meetings, but also transfer what they learn back to their peers in the network. In many cases, getting to desired outcomes may require that teams from a particular country or institution participate in the network, rather than just a single individual. A team approach fosters a greater sense of accountability, shared purpose, and motivation among participants.

Collaborative Learning relies on experienced and skilled facilitators to effectively respond to participant demand and frame the learning agenda within relevant evidence and experience across countries. Effective technical facilitation requires not only in-depth technical knowledge, but the ability to listen to and learn from practitioners’ experiences, elicit and synthesize lessons, and “co-create” useful knowledge products. Ideally, a Collaborative Learning facilitator should have knowledge of and experience across multiple countries/members and be focused on supporting participants to solve an actual problem in a defined period of time.

Effective Collaborative Learning facilitation must support all stages of the Collaborative Learning lifecycle. This requires identifying the “right” participants, conducting technical scoping and demand identification at the start of a learning initiative, offering engaging, demand-driven learning opportunities throughout the learning cycle with a consistent cadence of activities to maintain momentum, and documenting the learning in accessible products that facilitate the adaptation and uptake of learning in the participants’ local contexts and can be disseminated as global public goods for the benefit of others.

Learning activities should be structured as interactive peer learning and problem-solving sessions (workshops, webinars, country pairings, collaborative problem-solving sessions). These sessions require intense preparation by the facilitation team beforehand and active follow-up and continuous engagement after.

In addition to the structured learning engagements, Collaborative Learning facilitators often play an important role in providing on-demand support to participants, as feasible. This is an important part of the value proposition of a CLN.

Effective CLNs invest in a strong central team that operates in service to its members. Running an effective CLN takes significant effort and skill. Very rarely can members themselves simultaneously meet the demands of their role as policymakers or implementers, and also run a sustainable network. The strongest international CLNs have central teams whose primary professional focus is the success and health of the network to accelerate member impact. Effective central teams perform a number of functions to ensure the network runs smoothly:

The network manager may also provide financial management on behalf of the network (e.g., grants management to technical partners or on-demand learning funds) and may be responsible for fundraising.

Network management can be a good role for globally connected INGOs (international NGOs). These organizations often have institutional capacity to manage country engagements, fundraising, communications, knowledge management, and monitoring and evaluation — while also bringing deep technical expertise, which contributes to more skilled and effective facilitation.

CLNs can use a variety of supportive approaches to help participants adapt and implement the learning in their local contexts. The first core approach is ensuring the learning topics and activities engage the right change agents and are demand-driven and problem-solving focused to foster a strong sense of ownership and commitment by those that can act upon the learning. Country teams within some CLNs may have established processes for briefing colleagues and senior leaders at home through policy memos after learning engagements or organizing briefing sessions, learning forums, or policy dialogues with relevant implementers and policymakers. For example, the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center (SPARC) has organized validation workshops and policy dialogues in Burkina Faso and Rwanda to present and discuss analyses generated by the network, and generate policy and implementer engagement and commitment to address the findings.

A CLN with members from around the globe can cascade learnings regionally via hubs for learning, and to subnational levels such as in Colombia and India where the World Bank has supported subnational exchanges connected to global platforms such as the Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage (the JLN) and the Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI), respectively.

Other approaches include developing strong knowledge management and communications strategies to effectively package and disseminate learnings both within the network and as global public goods. CLN products can take various forms, such as toolkits, process guides, checklists, diagnostic and assessment tools, country case studies, synthesis briefs, videos or podcasts, blogs, and e-learning modules — but the key is packaging content in practical, concise formats accessible for busy implementers and policymakers.

The CLN can also build and broker partnerships with other global development initiatives that can support network members. The World Bank has played a key role in connecting JLN members and learning initiatives with ongoing World Bank-supported projects. USAID projects and mission-support can be another potential source of technical assistance for CLNs. For example, policymakers and practitioners in Ghana and Vietnam received in-country support from the World Bank and USAID to apply JLN knowledge products such as the Costing for Provider Payment Manual.

Often the impact of a CLN comes from what its members do outside of the network; the connections from the network they collaborate with, the initiatives they are inspired to lead as a result of the network, and how participants adapt and implement the learning in their ongoing systems improvement efforts. Thus, it is important to find ways to “see the invisible” and identify how the CLN has contributed to systems strengthening and field-building impact. Effective CLNs are committed to measurement and learning — both of members’ progress, and of the network itself. Agreeing upon what to measure can be politically and technically challenging. Doing so across multiple contexts and then measuring a CLN’s impact on those contexts is even more difficult.

Thus, it is important that each CLN has its own unique and well-developed theory of change, where inputs and outcomes are clear at the outset. However, a CLN’s direction may evolve over time, thus milestones need to be set to give indication of early successes (e.g., measuring level and value of connections, qualitative stories), and the theory of change should be revisited on a regular basis so it can be updated to reflect CLN evolution. Further, a CLN’s impact is often non-linear, thus measurement and evaluation methods need to deal with this complexity.

CLN monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) methods need to focus on three levels:

MEL methods include administrative data (e.g., membership database, communications, and website analytics), participant feedback, member-surveys, organizational network analysis (ONA), outcome harvesting, and contribution analysis. More mature networks may prioritize impact evaluations.

CLNs have the potential to help their members significantly accelerate progress on difficult problems. However, system-level change takes time and, therefore, any action network intended to drive large-scale lasting results must be designed with the vision, staffing and financial resources to thrive for extended periods of time, often years. This is particularly challenging with CLNs in global development, that are often dependent on time-bound donor funding. To ensure adequate and long-term funding, CLNs need to develop and implement plans for sustainability after donor funding runs out. Sustaining networks requires a shift to more open-ended funding that is adaptive to changing circumstances. Sources of funding can include not only development partners and foundations, but governments, social enterprise initiatives, and members themselves (Social Change Networks Playbook for Practitioners and Funders (inHive)).

Network members and managers need to engage in donor relationship-building early on and garner the support of a range of partners, to ensure there is broad support and the CLN is not tied to one funder (THS-Joint-Learning-Network-Case-Study.pdf (rockefellerfoundation.org). As the JLN has matured, it has managed to attract funding from diverse sources — including Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, World Bank, GIZ, USAID, among other development partners. In addition, the JLN has also worked to track and quantify members’ in-kind contributions such as hosting network meetings, member time spent on network functions, and travel expenses for learning events, among others.

Check out our free, open-access e-course to gain a better understanding of Collaborative Learning methods and develop the necessary skills to facilitate the Collaborative Learning process effectively.