How technology transformed mass vaccination in Ghana,

as told by Ghanaian health workers

Editor’s note: Results for Development (R4D) interviewed members of the Ghana Health Service (GHS) to learn how the use of tablets had impacted their work. The names of health officials and workers in the story have been changed to protect their identities and encourage open dialogue.

In early 2021, Ghana awaited the arrival of its first shipment of COVID-19 vaccines. A year had passed since cases of the virus were initially reported in the West African country, triggering a national emergency. Now, Ghana was preparing to embark on its largest mass vaccination effort to date.

To ensure a safe and effective vaccine rollout, government officials at the national level would need to coordinate and collaborate with regional, district and sub-district leaders, as well as frontline health care workers. Realizing they would need to implement a strong safety monitoring system for the vaccination initiative, national leaders determined they would collect case-based information (including age, gender, location, telephone number, underlying health conditions, type and dosage of vaccine administered, as well as details of any adverse side effects). This information would also provide valuable decision-making insight, including where vaccination rates were high or where they lagged, and it would enable officials and health care workers to identify successes and challenges in real time, allowing them to better tailor their efforts to populations across the country.

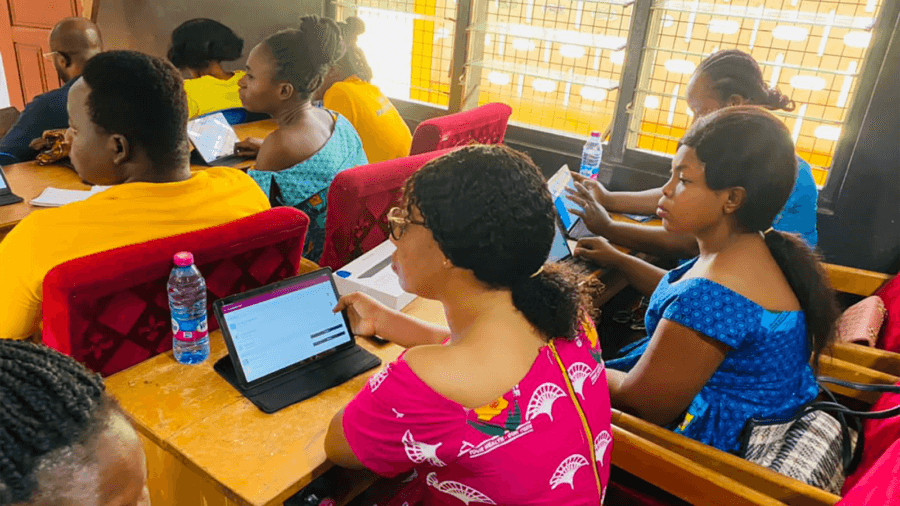

A member of the Ghana Health Service receives training to use digital tools for mass vaccination campaigns.

The Ghanaian government had extensive experience using digital tools for health service delivery, but this was the first time officials would collect case-based data — and they needed to rapidly scale up the effort across the country.

“We foresaw that a time would come when we would need the information about people who have been vaccinated. A time would come when we would need to have a good safety monitoring system in place since the vaccine was novel. And for accountability purposes, we needed this ourselves to make sure that we are on top of issues,” said Pascal Adu, a national-level systems analyst.

Adu added, “In as much as we were ambitious, and we knew we were going to hit the whole country, we also took note of the realities. What were the realities? That vaccines were not going to be available enough for deployment across the board at the same time. So that was where the use of data came on board. We had to focus on priority areas, and the data informed us that we had some hotspot areas that needed to be handled. We had to firefight those areas before looking at the less burdened areas.”

We had to focus on priority areas, and the data informed us that we had some hotspot areas that needed to be handled. We had to firefight those areas before looking at the less burdened areas.

To accomplish the massive task of capturing this data, the Ghana Health Service would equip workers with thousands of electronic tablets, delivered through a partnership between the Rockefeller Foundation, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and other partners. Through the Health Systems Strengthening Accelerator, Results for Development (R4D), a long-time partner of the Ghana Health Service, would facilitate on-the-ground training of health workers on how to use and implement the tablets.

How the Ghana Health Service deployed the tablets

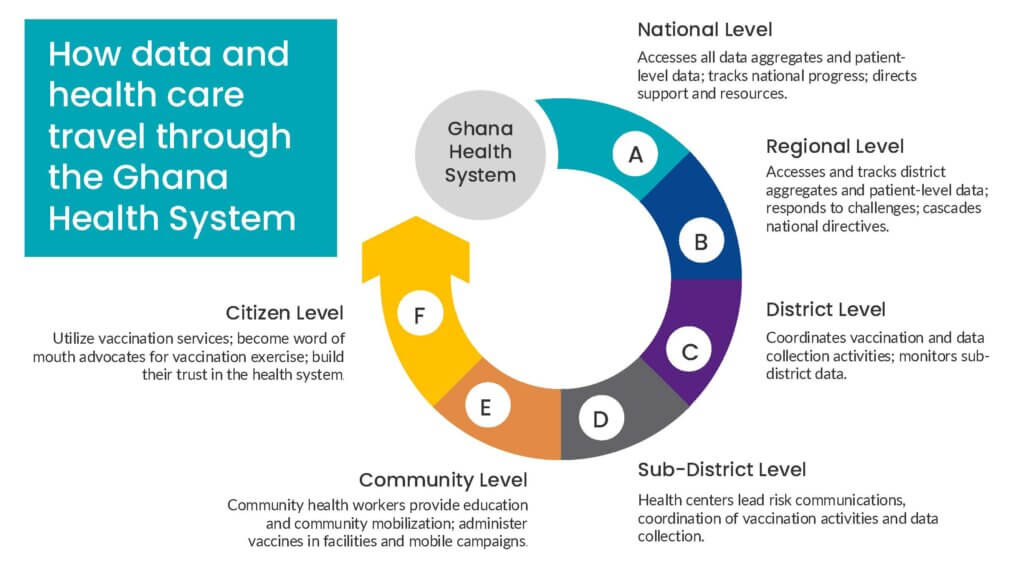

The Ghana Health Service operates as a multi-tiered service and administrative system. The national level is its highest tier. It oversees the work of and provides policy direction to regions, districts and sub-districts, each of which has its own administrative units and delivers some level of health services.

The Ghana Health Service managed the country’s vaccination exercise under this tiered structure. For example, tablets were disbursed from the national level to regions based on need. From there, the regional tiers of the GHS distributed the tablets to districts, which then distributed them to sub-districts. The smallest unit within the service delivery structure is the community health and planning service (CHPS) zones, which provide outreach and home-based services at the community level.

The success of Ghana’s ambitious vaccination exercise ultimately hinged on the frontline workers who have been vital in the country’s previous vaccination efforts. They would have to travel the breadth of the country and navigate rivers, lakes and poor roads. And for the first time, they were also being asked to collect extensive patient data.

Though Ghana had extensive experience using digital tools for health service delivery, this patient-level data tracker had only previously been in select regions for specialist clinics. The scale-up process for the COVID-19 data tracker, however, would be rapid and intensive. It would require continuous learning and frequent training on both the application of the digital tracker and the utilization of the COVID-19 vaccines, most of which was conducted virtually and cascaded from the national to the community level.

How digital tools were used to target areas with low vaccination rates

In coastal Ghana, health information officer Kofi Ntim received and disbursed more than 1,000 tablets by December 2022.

“The tablets have been a good data capture tool for real-time decision-making and planning interventions,” Ntim says. “We know which of the 29 districts are vaccinating more, and if a district has a low rate of vaccination, we can zoom in to see what the challenge is and decide if they need to do more social mobilization and create more awareness for people to get vaccinated based on the data coming from the tablets.”

If a district has a low rate of vaccination, we can zoom in to see what the challenge is and decide if they need to do more social mobilization and create more awareness…

Additionally, as data flowed back to district-, regional- and national-level GHS officials, experts parsed it to refine their community strategies, allocate resources and offer support to the areas that needed it most.

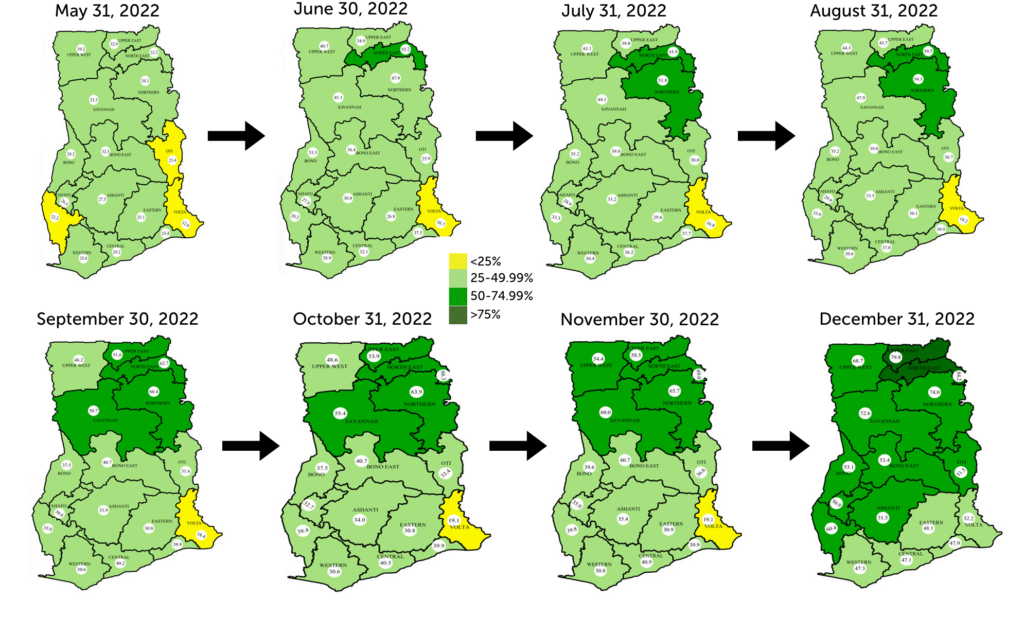

“Recently, I had to do some district-level analysis to see the proportion of fully vaccinated and categorize them,” Pascal Adu explained. “Once we categorize, we can fish out which district needed more support based on the percentage fully vaccinated. And that informed the push of some implementing partners in the northern zone. Now, as we speak, all the northern zones, with the support they received, have turned green because the proportions fully vaccinated have gone beyond 50%, some are even hitting 75% and above.”

Without that data, Adu said GHS would not have been able to identify which areas needed support, which would have made increasing the vaccination exercise’s performance more difficult.

How data and technology increased public confidence in vaccines and led to greater efficiencies

Across Ghana, health care workers have reported that their usage of the tablets to gather vaccination data has done more than offer insight — it has helped transform the way the public thinks about vaccines and health care.

In a densely populated sub-district on Ghana’s coast, Disease Control and Surveillance Officer Mariama Abdul reports that digitization has boosted the public’s confidence in the vaccination process in her locality, “seeing you’re not just writing their details on paper, but rather you’re entering it in the server they know that in the future they can retrieve their details later. It makes the people have that confidence that those coming around to vaccinate — they are not just vaccinating but they are very particular about the data they are capturing.”

Municipal Health Information Officer Boadu Asenso reports the digital system has had similarly positive impacts in his district.

“When the community members come and you can tell them, ‘I realize that you took your first jab at this location,’ it builds their confidence. They are able to tell other people, ‘look, they are recording what we’re doing so it’s good you go and take your vaccine’,” Asenso says, adding that the data ensures better continuity of vaccine coverage.

When the community members come, and you can tell them, ‘I realize that you took your first jab at this location,’ it builds their confidence. They are able to tell other people, ‘look, they are recording what we’re doing so it’s good you go and take your vaccine’.

In Kofi Ntim’s region, tablet usage has helped cut down on long wait times — or the perception of them — encourage more residents to take the vaccine.

“When there is a queue, it turns people away,” he says. “Using the tablets makes the queue move faster and encourages those who have been vaccinated to tell others that the process is only a maximum of 5-10 minutes.”

Mariam Abdul also noted health worker enthusiasm about the ability to do mobile campaigns, traveling out into the community delivering services from house to house.

“It isn’t like before when we would sit and wait for people to come to us. As a public health worker, we always want to go the extra mile to give people information and get them to use our services,” she said.

It isn’t like before when we would sit and wait for people to come to us. As a public health worker, we always want to go the extra mile to give people information and get them to use our services.

How health workers managed connectivity challenges and community differences

Though tablet usage has improved data collection and decision making, health care workers in some areas contended with unstable network connections or residents unfamiliar with the tablet technology.

Still, in those instances, frontline workers have remained committed to collecting the appropriate data with paper registers.

“What we’ve done is we’ve designed vaccination registry sheets which have all the basic information required, so as they do the vaccination, they do the appropriate documentation, then they bring it at the end of the day for the data officer [in the office] to do the data entry,” says Annowa Boateng, the District Health Information Officer of a rural, coastal district 60 kilometers from the city center.

In other parts of the country, such as inland Ghana, vaccination teams have worked with community volunteers to facilitate stronger local relationships and encourage more residents to get vaccinated. While some people may have initially seen holding a mobile device while talking as a sign of disrespect, health center midwife Naa Kwaley Quartey says clients adjusted to the digital tools.

“We needed to educate the clients that this is the new device that we are using to take care of you,” Quartey says. “After educating the clients they understand and they prefer the tablets to the books because they know the books can be destroyed or torn,” she said.

She says that she believes the use of digital tools has ultimately helped her subdistrict improve vaccination rates: “We know the number of people to be vaccinated and the tablets are helping increase our numbers because they make the work much easier.”

We know the number of people to be vaccinated and the tablets are helping increase our numbers because they make the work much easier.

Thousands of tablets, significant achievements, lasting impact

When it launched in March 2021, the goal of the National Vaccine Deployment Plan (NVDP) was to vaccinate 72 percent of the total population against the COVID-19 virus. By December 2022, the Ghana Health Service had made significant progress against its goal, delivering enough doses of the COVID-19 vaccine — some 21.4 million of them — to cover more than half the population.

Proportion fully vaccinated by region, May – December 2022

In some regions, vaccination rates have topped 75 percent, though in most regions the vaccination rate exceeds 50 percent. Development partners have supplied more than 6,000 tablets to the Ghanaian population since the start of the vaccination exercise.

Acknowledgements: Adwoa Twum and Katie Fly interviewed Ghana Health Service staff and wrote the case study that inspired this impact story. Alexander McCall wrote the impact story. This effort was funded through the Rockefeller Foundation and the Health Systems Strengthening Accelerator.