Advancing strategic purchasing in Africa through the government budget

The Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Centre (SPARC), a resource hub hosted by Amref Health Africa with technical support from Results for Development, is a go-to resource for African countries working toward improving allocation of limited health resources to further universal health coverage (UHC). The transfer of pooled funds to providers — known as purchasing — is considered strategic when purchasers deliberately direct health funds to priority populations, interventions and services. This creates incentives for health funds to be used equitably and aligned with population health needs.

SPARC is not just a resource center but a movement. SPARC is engaging as many stakeholder groups across Africa to understand, talk about, and advocate for strategic purchasing to make better use of limited resources for UHC and to hold governments accountable for effective health spending.

Between July 25-28 2022, SPARC convened 80 representatives from Ministries of Health, National Health Insurance agencies, the technical partners consortium, and coaches who support SPARC country engagements from 11 African countries ( Benin, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda). At this convening, SPARC hosted a learning exchange between these countries on advancing strategic health purchasing through the government budget.

Why the government budget?

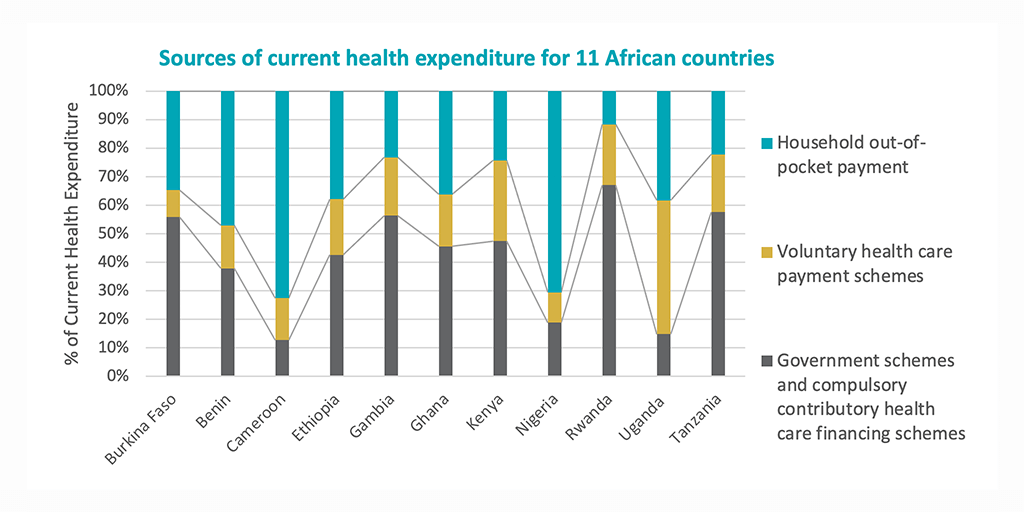

In many African countries, the government budget remains the largest pool of funds. Although the government budget has not been fully leveraged for strategic purchasing, there is growing interest in the region in introducing new health financing arrangements that operate in parallel with the government budget, such as contributory national health insurance, community-based health insurance, and other schemes. It’s clear the government budget remains the most effective and equitable vehicle for strategic purchasing.

It is widely acknowledged that more public resources are required to advance UHC objectives — and public funds — including on-budget donor resources channeled through the government budget, allowing for pooling and allocation of resources to providers in a way that aligns with population health needs. Recognizing the value of the government budget and the opportunities therein, representatives from Burkina Faso, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda, shared their country experience using the government budget to improve strategic purchasing and remaining obstacles to be overcome.

Resisting further fragmentation by channeling the government budget in existing schemes

Multiple schemes in countries, fragment health resources flowing through the schemes reducing the purchasers’ power to exert influence on how resources are allocated, and the incentives to providers for high quality care. When new schemes are established, often times they worsen the fragmentation in the system by adding a new scheme rather than building on what exists.

Tanzania’s Basket-funding, however, aimed to reduce fragmentation by pooling the government budget and on-budget donor resources into one pool and channeling resources directly to primary health care providers (PHC) through the Direct Health Facility Financing (DHFF) for priority maternal and child health (MCH) services.

In Nigeria, the Basic Health Care Provision Fund channels 1% of consolidated government revenue through three gateways to the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency to finance inputs for PHC providers; to the National and State Health Insurance Agencies to extend insurance coverage to vulnerable groups, and for emergency and pandemic related health services. In so doing, the government budget is building on existing purchasing agencies to transfer resources to providers targeted at PHC and addressing the needs of the most vulnerable population groups.

Prioritizing vulnerable groups and priority services

Channeling the government budget toward priority health services and/or population groups, such as women and children, in a bid to reduce maternal and infant mortality can move countries closer to achieving the sustainable development goals and UHC. The Gratuite program in Burkina Faso transfers government funds directly to PHC providers for MCH services. In Kenya, the “Linda Mama” program runs on a government budget subsidy channeled through Kenya’s National Hospital Insurance Fund for coverage of antenatal care, health facility delivery and postnatal care. In Uganda, budget guidelines stipulate that 30% of facility resources must be used for preventive health services and limits the district health facility budget spending on administration to 15% while the rest should be used for service delivery.

Using the government budget to increase provider autonomy

Provider autonomy refers to the degree of financial and management autonomy health managers have to receive funds, use these funds, and respond to the incentives in provider payment systems. Government budgets are associated with rigid rules for spending public resources to ensure accountability for how these resources are used but may limit how providers can spend resources they receive.

Tanzania’s DHFF recognized PHC providers as accounting units, allowing them to receive public resources, and expanded the decision space for managers to develop facility plans in collaboration with community representatives. DHFF also bypassed the bottlenecks and delays at the district level by transferring resources directly to the PHC level. This has allowed providers to be more responsive to local health priorities and allow more timely receipt of funds.

Burkina Faso’s Gratuite program also increased resources to providers and used a system of pre-payment that allowed for transfer of funds in advance to ensure adequate resourcing of providers and overcoming bottlenecks to resource flowing to the PHC level.

A similar program to transfer funds directly to PHC providers in Kenya, and increasing their autonomy implemented between 2010 and 2012, showed similar successes reducing bottlenecks at the district level, empowering providers to respond to local priorities and improving infrastructure at PHC level. Uganda provides strict guidelines to providers and follows this with supportive supervision and audits. Although this limits provider autonomy, these processes are considered necessary to improve alignment to national priorities and accountability for public resources.

Overcoming remaining obstacles

Despite these successes, there remain challenges in raising adequate resources for health, navigating the politics of moving money and power from one organization to another. For example, Burkina Faso is considering a transition of the Gratiute program to the health insurance agency; and in Kenya the devolved system of government has increased fragmentation of health resources in 47 county governments. Further, a debate on how much provider autonomy is sufficient and how to link the government budget to better performance and quality of care remain important learning questions for SPARC and the technical partners going forward.

For those considering changes in the government budget, it’s important to have a clear vision and strategy — and to look for opportunities to solve problems with steps that have the least resistance from stakeholders, while building trust along the way. For SPARC, this is only the beginning of a learning agenda that builds on these country lessons.

Photo © Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center