How COVID-19 affected vaccine procurement processes in Ghana

Collectivity Series: 4 of 5

[Editor’s Note: This is the fourth post in a blog series by Collectivity — an online collaborative learning platform for health system experts. This strategic purchasing series features insights from six different country teams that explored how governments have adjusted their health purchasing arrangements to support the COVID-19 response as a part of a project co-facilitated on the platform by R4D, the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center and the World Health Organization. In this post, however, the team explores adjustments to procurement arrangements and the vaccine program that Ghana developed as a result of COVID-19.]

Ghana has been successful in building a strong system for immunization of routine vaccines over the years. In 2019, immunization coverage for essential vaccines was in excess of 90%, and Ghana has not recorded a single death from measles since 2003. In addition, it was certified as having eliminated maternal and neonatal tetanus in 2011. This infrastructure supports Ghana’s enviable record in immunization coverage that has helped reduce infant mortality and the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles.

There are multiple prongs to ensuring strong vaccine programs, including public procurement, supply chains, and the public financial management processes that ensure accountability and adherence. This post provides an overview of Ghana’s vaccine program and how the various contributing prongs have contributed to or detracted from the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines.

COVID-19 and vaccine rollout in Ghana

Ghana recorded its first COVID-19 case on the 12th March 2020 with two cases from Norway and Turkey. Subsequently, as the number of COVID-19 cases increased, Ghana enacted the stringent policy of lockdown from March 30–April 20, 2020 in Greater Accra and Kasoa and Greater Kumasi to reduce the spread and enhance COVID-19 management as these areas were described as hotspots. According to the Ghana Health Service (GHS), the COVID-19 case count as of Dec. 1, 2021 stood at 131,246 with 129,326 recoveries and 1,228 deaths (GHS, 2021).

COVID-19 vaccines such as the Sputnik-V, Atrazeneca, Janssen, Moderna, and Pfizer BioNTech have been approved and are being administered in Ghana. On March 1, 2021, Ghana began vaccination with 600,000 Astra Zeneca vaccines as the first to be administered as part of the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative. Following this, batches of the Sputnik-V, Atrazeneca, Janssen, Moderna, Pfizer BioNTech have arrived in the country and are being administered accordingly.

For the initial COVID-19 vaccine rollout, the country reached 60% of its first phase target population and around 90% of all health workers in the first 20 days. The total number of COVID-19 vaccines administered as of Dec. 3, 2021 stood at 5,724,634 representing a share of 18.6% of the 30.8 million population (GHS, 2021).

The vaccines are comprised of 4,866,560 AstraZeneca, 467,230 Moderna, 199,655 Pfizer BioNTech, 173,207 Janssen and 17,982 Sputnik-V vaccines. The government of Ghana aimed to procure and administer 17.6 million COVID-19 vaccine doses in the first half of 2021 (Reuters, 2021) but this target has not been met. Initially, Ghana’s cold storage facilities lacked the capacity to house some vaccines like those manufactured by Pfizer and Moderna – limiting the COVID-19 vaccine options available to Ghana. The government procured some ultra-low temperature freezers and cold storage boxes to store the vaccines that require very low temperature to keep vaccines safe for use to shore up the vaccination rate in the country (CITI TV, 2021; UNICEF, 2021). The rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccines in Ghana was also dependent on timelines and the scale of delivery of existing arrangements.

A multi-pronged approach to assessing the vaccine program

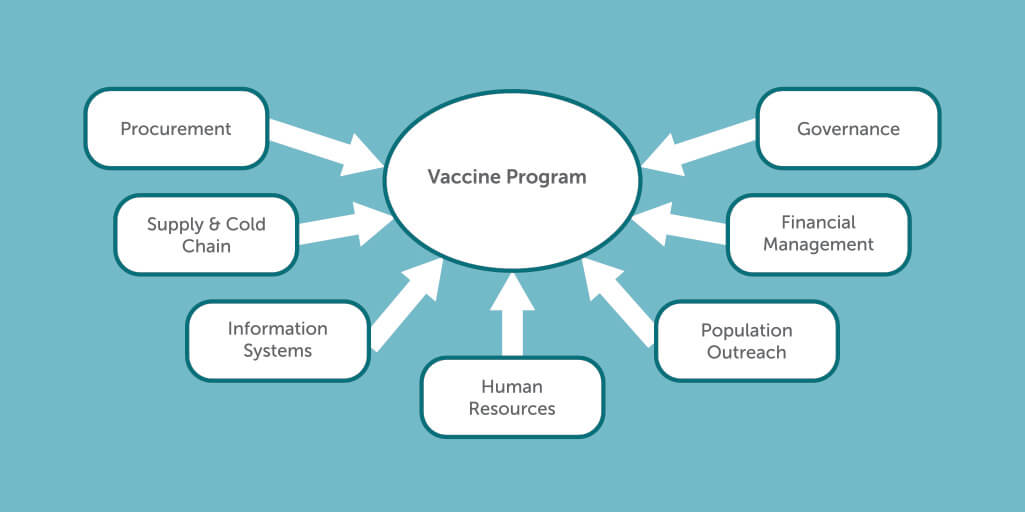

Efficiency in public procurement is of importance in ensuring that the best value for money is obtained by public entities. However, the supply of vaccines is only one measure of a successful vaccine program. A successful program for delivering COVID-19 vaccines should consider 1) procurement systems and processes, 2) Supporting systems like the supply chain warehousing and 3) technology, monitoring, surveillance and information systems processes, 4) human resource capacities, 5) population outreach 6) financial management and 7) governance including policy, legal and regulatory processes and institutional roles and responsibilities (Figure 1).

If conditions are improved for procuring and supplying COVID-19 vaccines, more vaccines will be provided, the health impact of the pandemic will be lessened, and the entire country will benefit via enhanced productivity. Further- barring any negative impacts from reallocations- the resilience of the entire health system will be improved. The following section outlines the state of related vaccine program processes in Ghana and adjustments made for COVID-19 in these areas, with a focus on procurement.

Figure 1: Processes to Ensure Effective Vaccine Program and Positive Impacts

Procurement adaptations for COVID-19 vaccines and supplies

Procurement adaptations for COVID-19 vaccines and supplies

At the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, the Minister of Health in the exercise of the powers conferred on him under section 169 of the Public Health Act, 2012 (Act 851) by Executive Instrument declared the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) a public health emergency.

These emergency processes generally allow for direct negotiations with vaccine manufacturers thereby removing the competitive tendering process as stipulated by the public procurement Act 2003 (Act 663) as amended.

Unlike developed nations, Ghana like other developing countries has limited bargaining power to negotiate directly with manufacturers. As a result, it is principally relying on two multilateral initiatives to procure COVID-19 vaccines — the COVAX facility and the African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT). However, participating low- and middle-income countries under these arrangements are expected to receive enough vaccines to cover up to 20% of their populations.

The MOH made both multilateral arrangements like the COVAX and bilateral arrangements with manufacturers for the supply of COVID-19 vaccines and was guided by laid down principles for the vaccine, including market authorization, availability, quality, safety, efficacy, ease of administration, storage and cost. An independent committee of experts, the Joint COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Review Committee, has been put in place by the FDA to review safety information from the COVID-19 vaccinations in Ghana. This expert Committee makes recommendations on the benefit-risk balance of the vaccines to ensure that the COVID-19 vaccines continue to protect people against coronavirus disease and are safe.

On Feb. 24, 2021, Ghana made history by having been the first country in Africa to secure 600,000 Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccines under the COVAX arrangement. On 7th May 2021, Ghana received additional 350,000 Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccines from the Democratic Republic of Congo, through the COVAX facility. On August 8th 2021, 177,600 Johnson and Johnson vaccines were received through the African Union’s African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT) initiative. On 17th August 2021, 249,000 AstraZeneca was also received from the UK government.

Between September and October 2021, more than 5 million more vaccines including AstraZeneca, Johnson and Johnson, Moderna, Sputnik-V, and Pfizer have been procured through bilateral and multilateral means from the United States, Germany, Norway and Denmark and through the COVAX facility and AVATT bringing the total vaccines received to close to 7 million vaccines.

Supply and cold chain components

The rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines was expected to be done on the existing vaccine cold storage units used by the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) for the child immunization program.

For any ultra cold chain, the government would be expected to invest in completely new installations. To address this challenge, the government has proposed to purchase 300 minus 200 C to minus 800 C refrigerators (one per health district (270), one per region (16) and the rest for teaching hospitals and headquarters cold rooms. This will enable the facilities to receive other variant vaccines that any of the development partners may propose to provide. From past campaigns, the current cold chain infrastructure is estimated to have a capacity to contain over 5 million vaccines. The Ministry of Health and its Agency, the Ghana Health Service has strengthened cold chain activities that have enabled the successful and safe storage of the COVID-19 vaccines that have been received so far.

Monitoring, surveillance and information systems

So far, building on the existing information systems in the country, the Project Implementation Unit (PIU) that has been in charge of the vaccine deployment has been effectively monitoring the progress of the key results indicators.

The Project Implementation Manual (PIM) was developed and is being implemented. It forms a key part of the monitoring and evaluation system of the vaccination program by the Ghana Health Service.

An electronic tracker (e-tracker) was also launched for effective management of the records of individuals who have received the vaccine, which can send a reminder for people due for a next shot via a text message. The District Health Information Management System (DHIS2) platform has been intensively engaged for the COVID-19 vaccination data aggregation. Vaccination cards are provided for every vaccine received by an individual with the Ministry of Health set to issue an enhanced COVID-19 card to fully vaccinated persons to enhance authentication. All supervisory tools for the process are electronic Open Data Kit (ODK) and all monitors and supervisors have been trained to use these tools.

An appointment system using an App (VaccineUPP) is currently being piloted as part of the ongoing Health Care Worker vaccination. According to the Director for Technical Coordination at the Ministry of Health, this innovation has played a pivotal role in Ghana’s successful rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines where the use of the electronic system has facilitated the registration of all vaccines, virtual platforms for training, various Apps to enhance work, among others could be credited for the milestone.

Human resources

The Ghana COVID-19 Emergency Response on Vaccines included the recruitment of technical experts and human resources to support intensive work on surveillance, contact tracing treatment and vaccination.

It further asserts that capacity building for health professionals such as doctors, staff of quarantine facilities, surveillance and rapid response teams is key for successful vaccine deployment. This was a critical element in the success of the COVID-19 vaccine rollouts.

Population outreach

The country invested in pre-listing the populations identified for the first phase of the vaccine rollout.

Activities included mapping populations, screening people and scheduling appointments for vaccination in advance. Also, investments were made in the training of staff to communicate to the public through well-planned work with radio, TV, social media and trained spokespeople, influencers, partner organizations and among communities. Virtual and in-person microplanning and training sessions for vaccinators and supervisors, additional vaccination sites, structures client flow, are some of the measures that were put in place for effective delivery of vaccines. These skills have strengthened the workforce’s ability to engage in future programs.

Financial management

The government has intensified efforts to mobilize financial support to procure vaccines for use from both state and non-state institutions.

To curb the adverse effects of COVID-19 as well as provide the requisite funds to sustain the implementation of the increased health expenditure measures, the government introduced a COVID-19 Health Levy. This levy is set at a one percentage point increase in the National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL) and a one percentage point increase in the VAT Flat Rate. This implies an increase in the NHIL from 2.5% to 3.5% and the VAT flat rate from 3% to 4% which have been earmarked as the COVID-19 Health Recovery Levy. The imposition of the levy is on the supply of goods and services made in the country, and on the import of goods or services unless exempt (EY Global, 2021).

On the non-state side, the World Bank approved the $200 million Ghana COVID-19 Emergency Preparedness and Response Project Second Additional Financing which is expected to procure COVID-19 vaccines for 13 million people in Ghana (World Bank, 2021). The assistance is envisaged to strengthen the health system of Ghana to withstand future shocks in the health sector. The government has partnered with Japan and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to secure nearly US$1 million to procure 30 new ultra-cold chain equipment to keep vaccines stored at very low temperatures and also train over 140 health personnel in operating the cold chain storage and vaccines distribution (UNICEF, 2021). This investment is meant to increase access and make a variety of vaccines available for use (ibid). Other financial and technical supports has come from the United States, France, Germany, Norway, and Denmark to make a variety of vaccines available to the government for onward distribution. These efforts have ensured that there is increased COVID-19 vaccines and varieties thereof for use.

Governance

The operations of the government and its agencies and the mechanisms they have employed in vaccine procurement has increased vaccine availability in the country.

The vaccine deployment was done in phases to target the large population. The first phase targeted people who were at high risk of infection and frontline state officials. The second phase targeted other essential workers and people in security services and the third phase targeted the rest of the general public especially people 18 years and above. The Ministry of Health headed by the Minister of Health fronts the official negotiation and procurement of vaccines for the country and liaises with the Ghana Health Service (GHS) to oversee the implementation of national COVID-19 policies of the ministry at the regional, district and sub-district levels. Similarly, the FDA, a WHO Maturity Level 3 regulatory agency has been charged to grant Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to expedite the approval of COVID-19 vaccines for use while also adhering to a strict standard of safety, efficacy and quality. The Ministry of Information holds frequent briefs on TV, radio and social media and invite technical experts to provide updates on the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines availability to intensify awareness of the pandemic and vaccine uptake. Equally, the GHS website provides official information on the COVID-19 pandemic, case count, vaccination rates, and deployment.

***

With strong leadership and coordination from the Ministry of Health, partnerships across and beyond government have proved crucial in countries that have shown early successes. There is the need for multisectoral partnerships to be in place at the national, district and local levels, including international partners and businesses, especially if official resources are over-stretched.

Public procurement responses as part of a coordinated public governance response are promoting inclusive growth and increased trust in governments. The key to a government providing a more streamlined delivery of public services to its citizens – in terms of both quality and time — is to use procurement as the interface through which their citizens can “plug in” to a new normal where trust is the standard. Creating more resilient and innovative government through better equipped public procurement systems will help governments to react properly to future crises and enhance the supply chain system integration of the health sector.

Photo © Francis Kokoroko/UNICEF

Catch up on the Collectivity Blog Series