What does it take to improve funding for primary care? A shared learning journey from Nairobi to Jakarta

What does it take to move money through complex health systems, so it actually reaches primary health care providers and improves service delivery? This question brought together a group of policymakers and practitioners across three continents as they worked together to contextualize and examine how primary health care (PHC) financing reforms happen in practice.

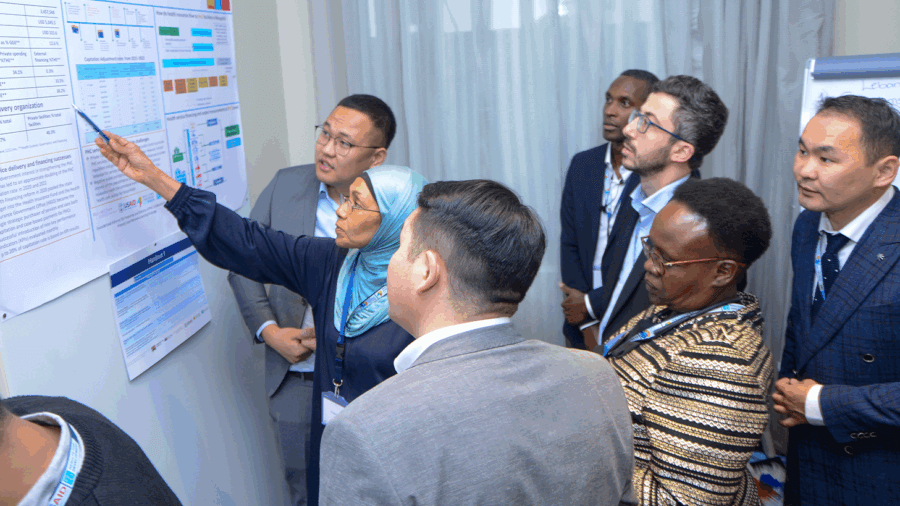

Through the Joint Learning Network’s Primary Health Care Foundational Reforms Collaborative, participants from 14 countries — Botswana, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Ghana, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kenya, Liberia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mongolia, Nigeria, Philippines and Vietnam — engaged in 18 months of shared learning focused on one core objective: improving the flow of resources to the frontline of care. Their experience offers practical lessons for countries seeking to make PHC financing reforms both feasible and sustainable.

In this final blog post, we summarize the key lessons from the collaborative, highlighting how countries are taking steps to improve PHC financing and get resources to the primary care level. The message is clear: reforming PHC financing and delivery is possible, and it is already happening.

Lesson 1: There are levers that countries can use to improve the use of PHC resources.

In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), PHC receives a low share of public spending, contributing to high out-of-pocket expenditures and lower quality health services. Addressing the root causes of inadequate, fragmented PHC financing requires strong political will and leadership that prioritizes PHC and long-term systemic actions, such as improvements in the macroeconomic and fiscal environment. But there are also levers that countries can take advantage of in the short term to improve use of resources at primary care level:

- Applying resource allocation criteria that prioritize PHC and take into consideration the population’s health needs to reduce health disparities.

- Making provider payment more strategic by implementing systems and policies that allow for the provision of promotive, preventive and curative services.

- Expanding the autonomy and decision space of PHC providers to inform allocation and use of PHC resources.

- Improving financial and organizational management skills of PHC managers to efficiently plan, use and account for public resources.

- Establishing service contracts and agreements with PHC providers to clarify expectations and quality standards for health services.

- Re-organizing and integrating service delivery into networks to pull resources to PHC, while also allowing providers to share resources and enhance efficiency.

- Engaging community members as accountability champions and advocates for increased allocation of resources to PHC.

Lesson 2: Commitments to PHC must be matched with adequate public resources.

Primary health care is the backbone of universal health coverage and can deliver cost-effective care that reduces long-term burdens on health systems and enhances equity, especially for rural and underserved populations. But this recognition has not yet been matched with adequate resources.

Lessons from the Western Cape province in South Africa demonstrate that setting clear objectives is an important first step in the design of a resource allocation formula that prioritizes PHC. These objectives are encapsulated in the criteria used to allocate resources and may be used to improve equity in resource distribution. Engaging a variety of stakeholders during the refinement of resource allocation models can build consensus without creating any “losers”. Overall, the goal is to channel resources to the point of care — to improve access to good quality health services with financial protection — and advance universal health coverage.

Countries are also testing needs-based approaches for budgeting. For example, Kenya and Nigeria are using population-based formulas, Ethiopia is factoring in age and community health needs in their allocation mechanisms, and Mongolia is linking budgets to performance indicators through performance-based budgeting.

Lesson 3: Countries are designating levels of provider autonomy along a continuum, based on their financial management systems and provider capacity.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for provider autonomy, but countries are working within their contexts to enable providers to influence allocations and spending to meet community needs.

In Botswana, Malaysia and Vietnam, PHC providers have no financial autonomy, and resources are managed at the subnational level. However, providers contribute to local budgeting and prioritization processes, influencing how PHC resources are allocated and used.

In Burkina Faso, Kenya, Ghana and Indonesia, facilities have some autonomy over user fees and insurance reimbursements. With this level of independence, they can manage operational expenses, purchase medicines and supplies, and hire non-clinical staff. However, it is common to find burdensome pre-authorization and accountability controls that limit resource use at the PHC level.

In Mongolia and Colombia, providers have substantial autonomy, including planning, budgeting, and spending. Countries that grant high levels of autonomy are also implementing guardrails to ensure responsible financial management.

These experiences have helped clarify what provider autonomy looks like in practice and how it can be structured across different contexts. At the same time, they underscore that autonomy is not an end in itself, but a means to better service delivery.

As countries consider whether — and how — to expand autonomy, several questions must guide that learning process: How much autonomy is optimal in different contexts? Under what conditions does it translate into improved service delivery and health outcomes? What accountability mechanisms strike the right balance between flexibility and control? And how can progress be measured over time?

Lesson 4: Countries need to adapt their Public Financial Management (PFM) systems to facilitate use of PHC resources.

Strong PHC systems require budget allocations that are both credible and based on realistic assessments and flexible enough to adapt to changing needs. Streamlined processes support timely release of PHC funds that can empower providers to access, manage, and be accountable for public funds. Output-oriented reporting should focus on measurable outputs, rather than just inputs.

However, efforts to shift toward PHC-oriented systems are hindered by existing PFM rules that are ill-suited and that hamper the flow and use of resources at PHC level. PFM systems not aligned with PHC can exacerbate mismatches between budget allocations and priority PHC needs, limit flexibility in fund utilization, and fail to ensure accountability for key health-related outcomes.

Several countries in the JLN Foundational Reforms Collaborative are aligning PHC budgets with policy priorities as part of broader PFM system modernization efforts. One notable reform is Program-Based Budgeting (PBB), which involves restructuring the budget by grouping line items into policy- or output-oriented envelopes.

Evidence suggests that when the program budget integrates primary care, PHC becomes more visible and trackable, and this can yield benefits for primary care spending. It enables flexibility in re-allocations within budgetary programs and can contribute to accountability by establishing performance monitoring frameworks that link financial performance indicators.

To effectively finance primary care through program-based budgets, countries should meet the following requirements:

- Embed PHC as a subprogram within the broader budget structure to facilitate care coordination, rather than as a standalone program.

- Keep the program-based budget structure consistent at subnational levels. When primary care is embedded as a subprogram, this structure should be maintained across the different subnational levels (regions, province, or districts) to enable consistent prioritization and expenditure tracking.

- Integrate PHC operating costs (such as staff, drugs, equipment) into the primary care budgetary envelope to reduce financial fragmentation and inefficiencies.

- Align budget formulation with payment modalities. Budgets should be formulated and aligned with how primary care providers are paid for services. This will allow program managers to select the most context-appropriate blended provider payment methods to incentivize quality services.

- Align program-based budget monitoring frameworks with PHC outputs to track both financial and non-financial performance of primary care services. Monitoring should be based on consistent and measurable primary care goals and indicators.

While many countries are using the program-based approach in their budget formulation, disbursements often still follow line-items, limiting the ability to highlight and track PHC as a priority. Few countries are integrating financial and non-financial performance monitoring into their PBB frameworks, missing the opportunity to link primary care financing to outputs and outcomes.

Amid dwindling external resources, countries are taking urgent steps to address the root causes and consequences of inadequate financing for primary care. These reforms require stronger systems, better data, and a willingness to shift power and resources closer to communities. And much has been learned through this collaborative about how to do this, but the journey of joint learning needs to continue to better understand which resource allocation approaches work best in different contexts, how best to adapt along the continuum of provider autonomy, and how to make budgets work better for PHC.

///

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the PHC Foundational Reforms collaborative members and the technical facilitation team. The authors also acknowledge the generous support of the Gates Foundation for funding the two-year collaborative.