Toolkit Home / Step 3: Data analysis and validation

Note: Data Collection (Step 2) and Data Analysis (Step 3) appear to be separate steps, but in reality, your first round of data analysis may require further data collection followed by revising and deepening your data analysis.

By the end of Step 3, you should have:

- Synthesis/summary of responses in the cells of the Excel tool Worksheets 1-4. This will form the basis of the Results Analysis (Worksheet 5) and application of the ‘Benchmarks for Progress in Strategic Health Purchasing’ (Worksheet 6).

- Completed the Results Analysis and Benchmarking.

- A list of findings — strengths, weaknesses and gaps — about purchasing at two levels: individual purchasers and across all purchasers (system-level).

- A list of conclusions that have been validated by key informants (e.g., purchaser staff).

- A preliminary list of recommendations to be explored with stakeholders.

- Gained the trust of stakeholders that the end goal is learning and progress towards strategic health purchasing, not judgement or finger pointing.

Tour the Data Synthesis and Analysis Tool:

3.1 Analysis of individual health financing schemes

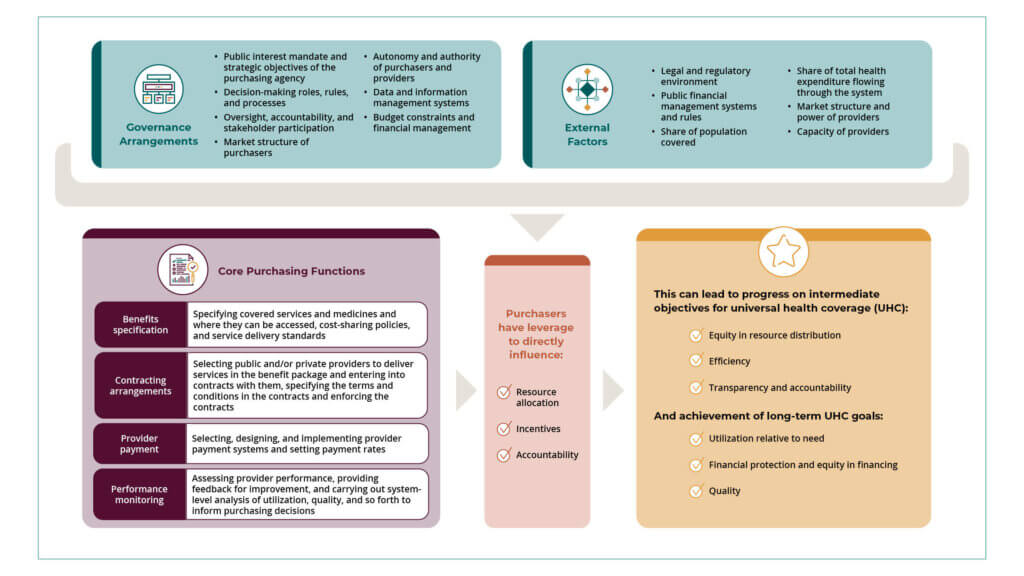

You will first analyze each health financing scheme individually to produce useful findings on operational issues related to the purchasing functions and related to results in terms of incentives to affect provider behavior, resource allocation, and accountability. This will lay the foundation for analyzing purchasing across the schemes at the system level.

Guidance for the first round of analysis:

- Begin with comparing the purchasing agency’s mandate/policies/regulations with actual practice to identify deviations and the possible reasons why.

- Use the Excel worksheet labelled “5) Results Analysis” to describe each scheme’s contribution to intermediate and long-term UHC objectives. First describe the “if” and “how” each purchaser has leverage to directly influence provider incentives, cost-effective resource allocation, and accountability for quality care; and the effects on intermediate UHC results (equity, efficiency, accountability, financial sustainability) and long-term UHC goals of utilization relative to need, financial protection, and quality. Refer to Table 4 in Step 2: Data Collection for examples of indicators to evaluate.

- Identify other strengths, weaknesses, and gaps of each purchaser based on key informant interviews.

As you perform the analysis, recall the three types of data you have been collecting (see Table 5).

Table 5: The Data Collection Tool allows you to collect three types of data: normative, actual and subjective.

| 3 Types of data | Examples |

|---|---|

| Normative How is purchasing designed to function according to its policies, law, regulation, annual plans? How does the design compare with the Benchmarks? | A) A benefit package was defined based on population health data when the purchaser was established 5 years ago. B) The purchaser has a policy of selective contracting according to explicit standards. |

| Actual How is purchasing functioning in practice per objective data? Note deviations from normative and from the Benchmarks. | A) The benefit package is well specified but has not been revised in 5 years. B) In practice any provider can participate. |

| Subjective What are stakeholders’ perceptions about actual practices and performance compared to how purchasing is expected to function (normative)? What do they perceive to be the reasons why there are deviations? Why is actual performance better/worse than expected? What solutions have been discussed or tried? | A) The process to revise the benefit package is not clear to stakeholders. B) The purchaser felt pressure to add more providers, especially in remote areas, and the ability to verify providers’ compliance with the standards is limited. |

Examples of common issues or themes for individual purchasing agencies

There is either no process or a vague/unclear process for regularly updating the benefit package because:

- The initial effort to define the benefit package was successful but did not anticipate or establish a process for regular updates/revisions.

- Lack of local resources and expertise for regular updating of the benefit package, for example health technology assessments, burden of disease and cost of illness studies, health demographic surveys, stakeholder consultations and other methods.

- Concerns that pressure from special interest groups (pharmaceutical and medical device companies; elite population groups; medical specialties, tertiary care providers) will dominate efforts to update the benefit package.

The purchasing arrangement (e.g., provider contracts) defines a package of services/benefits but providers are not accountable for service delivery standards because:

- Service delivery standards are the responsibility of a quality inspection or quality assurance agency, not the purchaser, and so service delivery standards were not integrated into the provider contracts.

- The link between the purchasing arrangement (contract) and service delivery standards is vague, not precise, and therefore impossible to measure and enforce.

- Patient data is mostly paper based. Few providers have electronic medical records. Very difficult and expensive to monitor provider adherence to service delivery standards.

Payment method is output-based, but does not affect provider behavior as intended due to:

- Delays in receipt of payment.

- Payment is an insignificant portion of the provider’s total income.

- Providers do not understand the link between the payment method and desired behavior.

- Other factors impede desired behavior or are more influential e.g., consumer preferences, professional beliefs, lack of necessary equipment/commodities/data.

3.2 Analysis of system-level results

Once the research team has a good understanding of each individual scheme, the next step is to evaluate the effects of the different schemes at a system level using the results analysis (worksheet 5 in the Data Synthesis and Analysis Tool).

Recall that the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework proposes that, through purchasing functions and governance arrangements, purchasers can directly influence (positively or negatively) results such as the allocation of resources, the incentives that affect individual provider behavior and accountability which in turn can affect the health system’s progress toward UHC goals. However, prior applications of the SHP Framework “…showed that a major challenge … was the weak link in their countries between health purchasing functions and their influence on improving resource allocation, incentives and accountability, as well as health system results of equity, access, financial protection, quality, efficiency and financial sustainability”.9 In other words, analysis of results is not easy, and is rarely attributable to a specific purchasing function in a single scheme. In addition, there are other social determinants of health that may improve access. For example, improving education of girls and women may delay them starting a family and/or improve the likelihood of contraceptive use or increase the likelihood of seeking a skilled health provider for delivery of their child. All these factors may contribute to an increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate, attendance of pre-natal clinics and delivery by skilled professionals which could all reduce maternal mortality. This is where the Framework helps by providing a practical way to look at the purchasing functions to identify improvements more directly attributable to strategic purchasing. For example, including immunization of children in the benefit package may increase the vaccination rate from preventable childhood diseases and contribute to the reduction of infant mortality.

Below are guidance and tips drawn from prior studies done in Kenya and Nigeria which documented how purchasing functions led to health system results:

- Strategic Health Purchasing in Nigeria: Exploring the Evidence on Health System and Service Delivery Improvements

- The Effects of Health Purchasing Reforms on Equity Access Quality of Care and Financial Protection in Kenya: A Narrative Review

Learn how these experts analyzed the data and how their findings are being used to improve strategic health purchasing in their countries:

Results analysis process

The research team may choose to convene a half-day meeting or mini workshop with the full research team and may also include the advisory group or technical working group. At this meeting, the team reviews the Results Analysis worksheet together, first by validating the scheme level results, and then agreeing together the combined effects of the schemes on each system level result. This is a facilitated process that requires a designated person to create a “safe space” for all attendees to voice any concerns they may have and allow for disagreement and debate.

Illustrative issues

Invariably, results are a mix of positive effects, gaps and limitations. For example, a scheme may have made good progress in improving resource allocation to high value primary healthcare services in rural areas. But if this scheme is very small in size and the effects are crowded out by other larger schemes that do not achieve this aim, at the system level there may not be changes in resource allocation and resources may continue to be skewed to high-cost services, or hospital care; or resources may be concentrated in wealthier urban areas. Reaching consensus on the responses to the Results Analysis questions will require deep and open discussion among the team on such complex issues.

Typical limitations to result analysis

- Lack of quantitative data that measures how purchasing affects provider behavior and other variables.

- The results of interest are influenced by many other factors besides purchasing.

- Lack of robust evaluation methods such as randomized control trials that isolate the effect of purchasing.

These limitations open up opportunities for new research questions that can be explored to better understand the effects of purchasing on the health system.

PRO TIP: For SPARC, there was a lack of evidence and/or weak linkages between the health purchasing functions and their influence on purchasing levers (improving resource allocation, incentives and accountability), as well as health system results (equity, access, financial protection, quality, efficiency and financial sustainability). This resulted in the technical partners digging deeper to make the linkages between the purchasing functions and effects on the health system in their countries.

3.3 Applying the benchmarks

Once there is consensus on the system-level results, the team reviews the Benchmarks worksheet on the Excel tool. This worksheet consolidates the normative guidance from existing purchasing frameworks and assessment guides created by WHO, the Joint Learning Network, and other sources to describe progressive steps or benchmarks towards carrying out each purchasing function most strategically. The proposed benchmarks provide a more granular description of the typical movement along the continuum from passive to strategic purchasing.

The Benchmarks worksheet has two main sections: (1) Benchmarks for progress on governance and institutional arrangements (three benchmarks); and (2) Benchmarks for progress on purchasing functions (eight benchmarks). The questions related to the benchmarks are dispersed between the “External factors and governance” and “Purchasing functions” worksheets, but are color coded to match each section of the Benchmarks.

The research team is facilitated through a discussion on each benchmark, first to describe each scheme and the progress they have made along each benchmark, and then a system-level analysis for each benchmark. This facilitated discussion should allow for all views to be discussed and debated, and consensus reached among the group. An outcome of this meeting may be that new data gaps are revealed and need to be filled, or additional data may need to be collected or verified with the key informant interviews. This may necessitate a subsequent meeting to discuss this new set of information and confirm if the conclusions drawn from the purchaser and system level analysis remain the same or change.

At the end of the meeting(s), the research team will have reached a consensus on the key strengths and gaps in purchasing and begin to propose some policy recommendations. The research team will also begin to identify some emerging issues such as:

- The existence of multiple schemes results in fragmented funding flows that reduces the purchasing power of individual purchasers to sustain cost-effective resource allocation, and create the incentives to providers and hold them accountable for high quality health services.

- Multiple funding flows and provider payment methods provide incentives to health providers to shift costs leading to a two-tier health system in which clients in some schemes are preferred by providers.

- If there are multiple payment systems, the incentives may not be aligned or even conflict with one another.

- Devolved systems of government lacking effective governance structures that articulate the roles of each level of government, and foster coordination toward national objectives, tend to worsen this fragmentation. In decentralized settings, the power of national purchasers may be diluted because subnational governments have authority over many decisions that affect resource allocation and incentives at the local level.

- Multiple benefit packages result in duplication of coverage for some population groups or services and gaps for other services.

- Multiple fragmented information systems do not provide the data needed to improve purchasing decisions or to monitor provider behavior to inform redesign of incentives.

Once the scheme and system level analyses — including the benchmarks — are concluded, the senior researcher within the team may review and validate the conclusions in the Results Analysis and Benchmarking made by the team before the Data Synthesis and Analysis Tool is submitted to external reviewers.

3.4 External peer review

We propose two external peer reviewers to review the Data Synthesis and Analysis Tool and individual Data Collection Tools for each health financing scheme. These peer reviewers may be the same individuals who provided the first technical reviews during data collection or a different set of reviewers. Both external reviewers should have health financing expertise but are not included in the research team. We propose that at least one should have country expertise, but the other external reviewer may be selected from another country to bring a “fresh eyes” perspective to the analysis.

The external reviewers should focus their review on the following questions:

- Is the data complete or are there any questions where more information or data is needed?

- Are the conclusions drawn in the “Results Analysis” and “Benchmarks” worksheet valid and a reflection of the data that has been collected?

- Are the strengths and gaps identified and the policy recommendations appropriate and reasonable, taking into account the findings and analysis?

The external reviewers will provide any recommendations or suggestions to complete the analysis and may require some additional clarifications. It may be more efficient to organize a virtual call to gather reviewer feedback, and it may require an additional review or reviews by external reviewers to

attain the depth and quality of analysis that is ready to share with a broader group of stakeholders.

3.5 Validation meetings

Once the research team is confident that the analysis is ready to be shared externally, the research team organizes a validation meeting. It is helpful to go back to the initial group of stakeholders that were engaged at the beginning of the assessment and invite them to review the findings. It is good

practice to invite all the different institutions that participated and provided key informant interviews.

It will be difficult to review all the data collected. Therefore the research team should develop a summary presentation that includes the following elements:

- The methodology

- Data sources – documents reviewed and institutions interviewed

- Summary of descriptive findings of the governance and purchasing function by scheme

- Results (intermediate and final coverage goals and benchmarks at scheme and system level)

- Strengths and weaknesses in strategic purchasing

- Policy recommendations to strengthen the gaps in strategic purchasing

It is good practice to send the slides in advance to allow attendees to digest the findings before the meeting. Adequate time should be provided in the meeting agenda to allow for discussion of the findings and to explore any issues that need clarification from the attendees.

The validation meeting is likely to reveal a number of areas that need further fine tuning and additional data to strengthen the results analysis, benchmarking analysis and the data sources to address the gaps.

Depending on the feedback from the validation meeting, it may require another validation exercise with a smaller group of stakeholders if comments are significant. If the feedback is minor, the research team can conclude the study and move on to the next step of sharing the findings.

Tips for developing recommendations:

- Help policymakers take practical steps to improve purchasing incrementally, in a way that can be scaled systemwide and is not limited to marginal innovations or a single purchaser.

- Be careful of a “quick fix” to solve a problem in one scheme that makes it more difficult to address a more important issue at the system level. Help stakeholders think long term and consider the whole health system across multiple purchasers. For example, a study in Kenya and Nigeria demonstrated that multiple funding streams each with their own payment mechanism provided incentives to providers that led them to shift costs, resources or services. In some instances10,11,12,13, it led providers to shift their attention to schemes that had more generous provider payment. In the U.S., private health insurance companies began contracting private companies to manage pharmacy benefits to control the high cost of prescription drugs for their beneficiaries. Meanwhile, people covered by government insurance or without any health insurance face the highest drug prices in the world in the absence of a system-wide policy solution.

- Good ideas can come from:

- Existing documents and your key informant interviews. In other words, the ideas are not new but have yet to move forward. Find out what the barriers are.

- Experiences from other countries and strategic purchasing literature. You should be proactively identifying relevant experiences and lessons. Look for ideas that are feasible, fit the country context, and put the health system on the path of system-wide improvements to more strategic purchasing.

- Policy dialogue events (see Step 4 below) where you bring together multiple stakeholders to consider the results of the Strategic Purchasing Framework study and discuss solutions.

For a full list of citations, see the pdf version of the toolkit.