Don’t forget the ‘softer’ engagement factors in public-private engagements for health

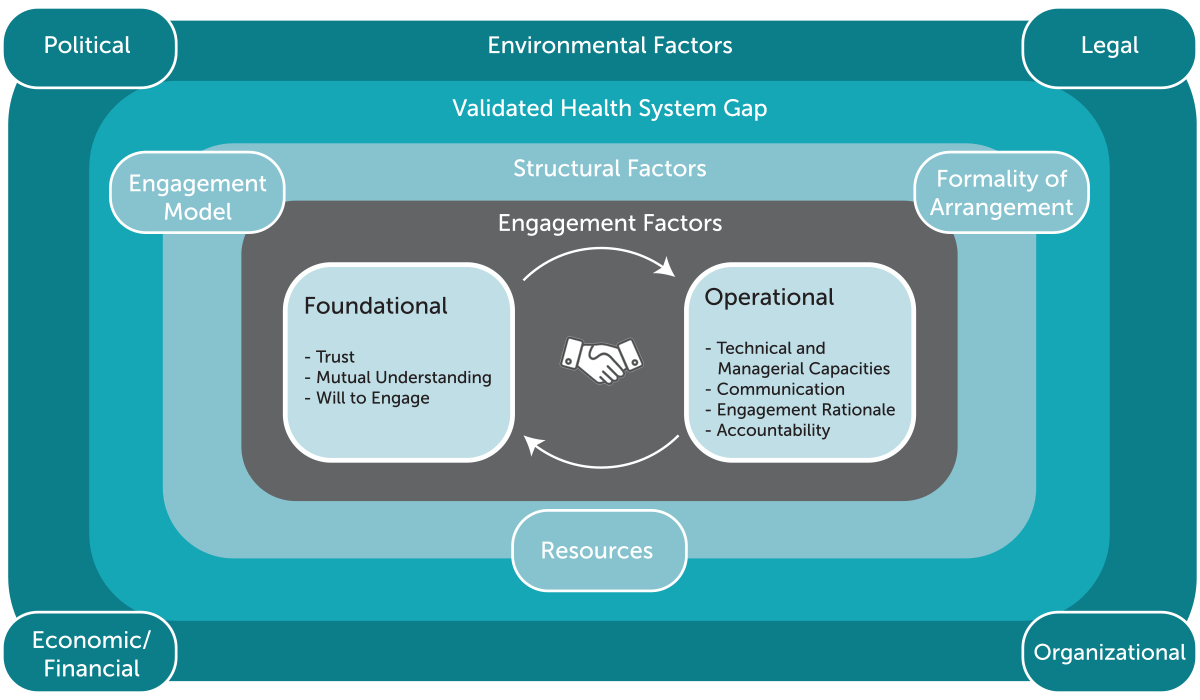

If you’ve been following our blog series so far, you’ll know we’ve been hammering home the importance of a holistic approach to public-private engagement (PPE) — one that recognizes a complex network of the environmental, structural and engagement factors necessary for effective engagement (see Figure 1).

Through both a review of the existing evidence base for PPE and our own practical experience, we’ve seen that while environmental factors related to the broader health system context and the nuts-and-bolts structural factors of an engagement — like resources, engagement models, and formal or informal engagement mechanisms — are important, core to the success of PPE are the “softer”, often-overlooked engagement factors.

In this blog, we hope to shine a light on the importance of the engagement factors — the capacities, relationships, and interactions between stakeholders involved in a PPE. We hypothesize that without a focus on addressing these factors, efforts to strengthen PPE may not be effective.

Figure 1

Within the PPE ecosystem framework, we expand this hypothesis by detailing two broad dimensions of engagement factors critical to effective PPE: foundational and operational.

- Foundational: The foundational dimensions include factors central to the relationship dynamics and interactions between the public and private sector actors involved in a PPE, including their level of trust in one another; their mutual understanding of each other’s roles, motivations, and capacities; and their willingness to expend time and effort engaging with one another.

- Operational: Building on the bedrock of the foundational dimensions, the operational dimensions include factors that support the overall functioning of a PPE. These include the rationale or overall goal for participating in a PPE, as well as the knowledge and skills of the partners — related both to the technical area of focus (e.g., maternal health) and the capacities to effectively manage the activities of the engagement. And, of course, the operational dimensions also include the communication and accountability mechanisms that support day-to-day operations.

We’ve seen these factors at play in the existing evidence base for PPE. Multiple qualitative studies in India, for example, have found that a trust deficit between public and private sector partners—often driven by negative perceptions and a lack of prior engagement — is responsible for hindering the effectiveness of engagements as diverse as a data sharing initiative in Uttar Pradesh and an engagement to promote facility births in Madhya Pradesh. On the other hand, an evaluation of a PPE for reproductive health training in Papua New Guinea stressed the importance of strong communication, mutual understanding, and an engagement rationale as enabling factors, finding that “regular partnership meetings for annual planning and quarterly reviews of progress assisted with creating shared understanding of health service delivery in the area.”

To help understand this concept of foundational and operational dimensions, we have been thinking about it like building a house: there are a lot of important things you need to install and operate in order to live in it comfortably, like walls, electricity and plumbing — but these things aren’t likely to be effective or long-lasting without a solid foundation. We think that without meeting a minimum threshold on the foundational dimensions (in other words, overcoming mistrust, negative misconceptions, and resistance to engagement), it’s unlikely that a PPE will be able to operate effectively. At the same time, operational dimensions, such as communication between partners, can help to improve — or erode — a foundation of trust and understanding over time.

As such, we believe that the foundational and operational dimensions run in parallel and can be linked in a virtuous or vicious cycle. In other words, if you find a crack in the foundation, you can fix it and make your house stronger — but if you don’t, over time the crack will grow and will eventually cause bigger structural problems.

Ok, so engagement factors are important, but how do we address them?

Most of us intuitively recognize that these engagement factors are important, but rarely do we systematically address them, nor do we know much about how to address them in practice. In our last blog, we took stock of the available guidance for PPE in LMICs and found that while there are ample resources for understanding the environmental, and, to some extent, structural drivers of PPE, existing guidance for addressing the engagement factors in health (and particularly in public-private engagement in health) is limited.

Given this dearth of guidance, we see two practical next steps: first, building recognition for the importance of the engagement factors and exploring how to assess and diagnose them, and second, using that knowledge to strengthen them.

On the first step, as part of the Strengthening Mixed Health Systems project, we’re sharing and using the public-private engagement ecosystem framework to raise awareness and recognition of the importance of the holistic approach to PPE. We’re also developing an engagement factors self-assessment tool to help public and private partners articulate and assess their own perspectives on the engagement factors and identify areas for improvement.

Let’s take trust as an example. The engagement factors self-assessment tool is designed as a questionnaire that asks both public and private sector stakeholders involved in a PPE to rate their level of agreement (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) with statements describing each engagement factor. To assess trust, the self-assessment asks for the stakeholders to share their level of agreement with statements such as the ones below.

- Representatives from our partner institutions act with goodwill and integrity as part of our engagement.

- If my institution needed support (e.g., equipment, human resources, training, consultation, etc.), our partner institutions would be willing to provide that support.

- When our partner institutions make a commitment related to a policy or implementation plan, they will follow through.

By looking across responses collected through the self-assessment tool, the stakeholders involved in an engagement can identify areas where their performance on the Engagement Factors is strong — for example, when responses indicate that there is a high level of mutual trust across the partners. Conversely, it can also help to signal where there are areas for improvement, for example, when responses indicate a low level of trust among the partners or when there is divergence across sectors, such as when private sector actors indicate a lack of trust toward the public sector.

These signals can help to pinpoint topics for deeper facilitated discussion between sector partners to understand the engagement factors and lead to actions for improvement, whether focused on building trust between stakeholders or ensuring that the engagement model is the right fit. We’re currently piloting this tool with a PPE in Maharashtra State, India, to make sure that this tool is practical and useful to PPE stakeholders and will then support the stakeholders as they think about next steps for strengthening their engagement.

In our next blog, we’ll dive deeper into our approach for strengthening PPE — including Engagement Factors, what we’re testing and learning, and how we’re planning to share those learnings. With new evidence and tools focused on the Engagement Factors, we’re hopeful that PPE actors will have the equipment they need to work out their “soft” factors and strengthen the effectiveness of their engagements. In the meantime, you can check out the draft Engagement Factors self-assessment tool — and provide feedback — by clicking the link here.

***

The Strengthening Mixed Health Systems project is supported by funding from Merck, through Merck for Mothers, the company’s global initiative to help create a world where no woman has to die while giving life. Merck for Mothers is known as MSD for Mothers outside the United States and Canada.

Photo © Sala Lewis, Vodafone Foundation