Important links between factors that affect public-private engagement

If you’ve been following along with us on this series, you know that we’ve already tackled some of the key issues in public-private engagements. We’ve broken down the ecosystem of factors that we hypothesize play a role in engagement outcomes (listed in the box below), discussed our approach to strengthening public-private engagements, advocated for the importance of engagement (soft) factors, and shared some of the findings from our primary case studies.

Factors in the Strengthening Mixed Health Systems Factor Ecosystem

- Environmental: Shaping the environment in which a public-private engagement operates (including political, financial, legal and organizational).

- Structural: Defining the architecture of a public-private engagement (including engagement models, formality, and resources for engagement).

- Will to engage: The intention, interest, or commitment of individual public-private engagement actor and their institutions to enter and sustain the engagement.

- Trust: The belief that the opposite sector is acting in good faith and has the goodwill and integrity to effectively participate in an engagement.

- Mutual understanding: The understanding of the opposite sector’s capacities, motivations, resources, and role in the health system.

- Communication: The process and approach used by sector partners to exchange information and participate in dialogue.

- Engagement rationale: The basis of and motivation for the engagement.

- Technical and managerial capacities: The capacities of public-private engagement actors related to the technical area of public-private engagement focus as well as project management and joint leadership.

- Accountability: The process and approach used by sector partners to hold one another accountable for carrying out their roles and responsibilities in the public-private engagement.

To strengthen the findings from our two primary case studies, we decided to do an in-depth investigation of public-private engagements previously studied in the academic literature to allow for cross-cutting analysis and broader conclusions about what works in public-private engagements.

First, we chose six public-private engagements from the literature involving local private sector actors that were well-documented and evaluated. Then, we analyzed the articles (and, where possible, new interviews that we conducted with implementers and researchers) using a validated factors codebook. Finally, we carried out a thematic analysis to understand trends in helping/hindering factors and outcomes.

Though our six case studies come from around the world — Bangladesh, Brazil, Guatemala, India and Malawi — we began to notice an interesting trend emerging across the cases. We realized that, across the board, factors were much more closely linked than expected: instead of existing independently, factors intersected and impacted each other.

Factors can play a big role in helping or hindering an engagement, and so it’s worth understanding the complex interplay and relationships between the factors that practitioners could leverage in strengthening engagements. Understanding how factors are linked, how they impact each other, and causal relationships (when possible) is important for strengthening both new and existing public-private engagements.

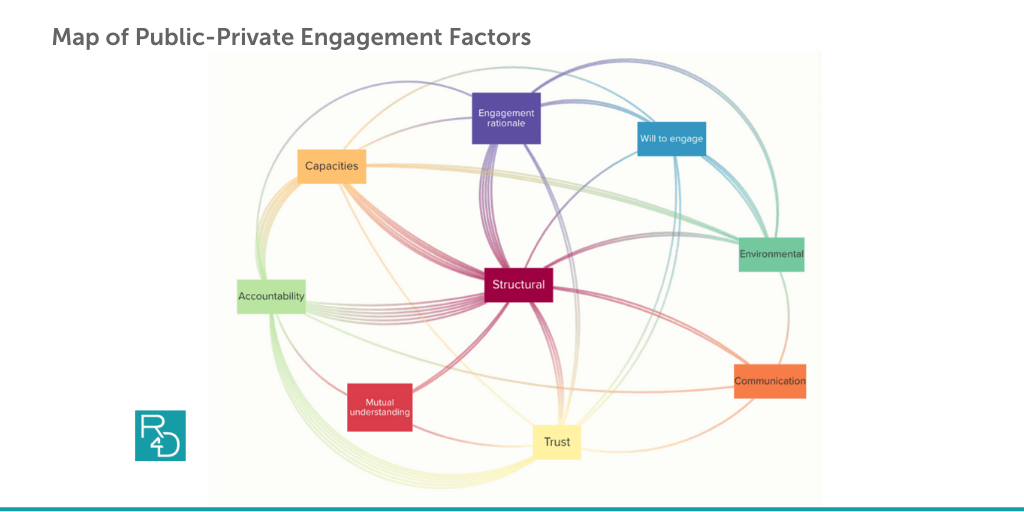

Intrigued by these emerging links, we wanted to know more — were there trends in these linkages? Were some factors more closely associated than others? Were there any temporal trends in linkages that could indicate the potential for causality? We carried out a system mapping to visualize how the factors were connected (Figure 1).

Figure 1 above depicts the map of connected factors in our six secondary case studies. A line between two factors indicates that the linkage appeared at least once within a case. Therefore, the highest possible number of linkages between any two factors on this map is six (which would indicate that the linkage showed up in every case).

A few key observations from the factor map

Some factors in the map are clearly more linked than others.

This may indicate that the highly linked factors are more important than those with fewer linkages, though we certainly can’t make any conclusions — we’ll call it a hypothesis worth studying more.

Structural factors showed up in all six case studies and is the only factor (out of nine total) that has linkages to all of the others.

Structural factors provide the architecture for a PPE, encapsulating its engagement model, resources and formality of arrangement. Structural factors, by definition, act as the framework upon which an engagement is built. There can’t even be an engagement without structural factors to shape it — it’s no wonder this factor is so heavily connected to all the others. These linkages showed up in our cases in many concrete ways.

In a public-private engagement in Bangladesh, the comprehensive contract structuring the service provision engagement between public and private sectors connected to the strong mutual understanding between partners on their respective roles/responsibilities.

In an example from India, on the other hand, private providers involved in the scheme reported delays in reimbursements for services from the government (structural), which was linked to the lack of trust between the two parties in the engagement.

We also noticed a strong three-way correlation between structural, accountability, and technical and managerial capacities.

This isn’t evident in the factor map above but, in our analysis, we noticed that these three almost always appear together. That’s to say, in a linkage between structural and accountability, technical and managerial capacities are likely implicated too. This could be because accountability mechanisms are usually included in the structure of an engagement and hinge on partner capacities to successfully implement them.

For example, in a case in Guatemala, the government increased their capacity to implement effective accountability mechanisms over the course of the engagement, which were laid out in the engagement’s structure.

In Malawi, a lack of accountability mechanisms laid out in the engagement’s structure at the beginning of the engagement, combined with a lack of supervision (capacities) to monitor accountability informally, were cited as contributing factors to a lack of trust between parties.

So why does this matter?

We get it — some of these factor linkages may seem intuitive (or, on the other end of the spectrum, overly academic) — so why did we take the time to create a factor map? We know from our earlier work that factors are incredibly important to PPE success.

The logical next question is “So how do we strengthen factors to ensure optimal public-private engagement performance?” This is where factor linkages come in.

Some factors, like trust, are difficult to directly impact. Trust must be built over time; especially if there is a history of challenging relationships, parties are unlikely to immediately trust each other, and it can be difficult to implement trust-building interventions.

What we could do, however, is focus on improving a factor that we know is linked to trust. For example, Figure 1 shows that trust is linked to accountability, communication, and mutual understanding — all factors that could be directly targeted. If we work to improve communication between parties, say through the implementation of quarterly partner progress meetings, we may be able to improve the quality of communication through positive interactions and begin to build trust.

Similarly, a public-private engagement lacking trust might benefit from a roles clarification exercise to improve mutual understanding, or systematic monthly monitoring visits to improve accountability.

Of course, in introducing this type of accountability into the system, it’s important to make sure that new initiatives don’t exacerbate existing power imbalances and that the goal is supportive supervision rather than over-regulation…which could have downstream negative impacts on the trust, instead of strengthening it.

It’s also important to understand linkages between factors because some factors are more difficult to change than others. For example, environmental factors — including the political, legal and regulatory environment — often take time and effort to change. It’s important to understand the impact of factors on others and compensate for them if necessary. Environmental factors are linked to will to engage and engagement rationale. If a public-private engagement’s environment could weaken any connected factors, we can provide additional support to those vulnerable factors in an attempt to insulate them from damage.

Overall, we believe that understanding the relationships between factors can help improve understanding of public-private engagement and provide levers for strengthening it.

The Strengthening Mixed Health Systems project is supported by funding from Merck, through Merck for Mothers, the company’s global initiative to help create a world where no woman has to die while giving life. Merck for Mothers is known as MSD for Mothers outside the United States and Canada.

Photo © Dominic Chavez/World Bank